The leveraged loan bubble

Lenders are writing cheques for highly indebted companies at record rates. What could possibly go wrong?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Ever since US subprime mortgage loans triggered the 2008 financial crisis, eyes have been trained on the debt markets, hunting for the next obscure credit product that could topple the financial system. The latest candidate in the spotlight is the leveraged loan market. What are they, and should we be worried?

Leveraged loans are, as Simon MacAdam of Capital Economics puts it, "syndicated" (ie, the money is arranged by more than one bank); "floating-rate" (ie the interest rate is not fixed, but goes up or down with prevailing rates); "non-investment grade" (ie, on the riskier end of the spectrum); "commercial loans" (ie, loans to companies rather than governments). Roughly $1.3trn in leveraged loans is currently outstanding, according to International Monetary Fund researchers Tobias Adrian, Fabio Natalucci, and Thomas Piontek. Writing on the IMF blog they note that new issuance of these loans hit a record $788bn last year. The previous high came (surprise, surprise) in 2007.

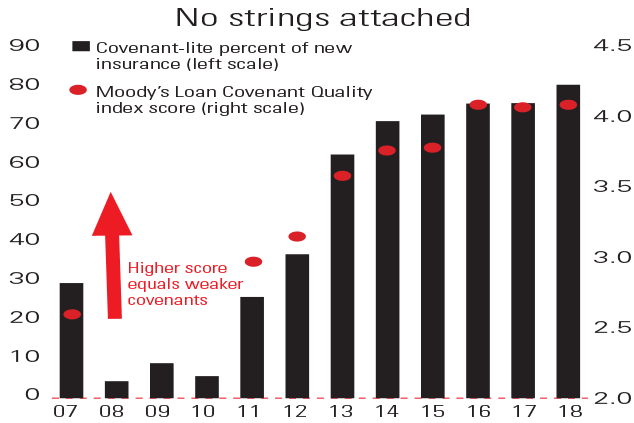

One reason leveraged loans have become so popular is that investors have been happy to buy debt with floating rates, due to expectations of rising central bank interest rates. Yet as lenders have competed to meet demand for the loans, lending standards have fallen. Not only are lenders giving money to companies that are far more indebted and riskier than those they loaned money to in the past, the loans also have fewer strings attached ("covenants" see chart). For example, a borrower might once have had to agree to maintain a certain minimum interest coverage ratio (see our financial glossary for more).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

"Lenders are lending money with far fewer strings attached"

Yet such lender protections have virtually vanished. In the US, notes MacAdam, "covenant-lite" loans accounted for roughly 25% of leveraged loans in 2007, to a record high of 80% now. As a result, when loans go bad, recovery rates (the amount the lender gets back if a company defaults) have fallen to just 69% compared with a pre-crisis average of 82%. On top of this, about half the loans have been parcelled up, subprime mortgage-style, into Collateralised Loan Obligations (CLO) and sold to institutions. "Institutional ownership makes it harder for banking regulators to address potential risk to the financial system if things go wrong," warn the IMF researchers.

Should we be worried? Not necessarily, reckons MacAdam. The big difference between now and 2008 is that banks are better capitalised and far less exposed to securitised loans than in 2007. That said, it's worth keeping an eye on the most exposed sectors for signs of trouble brewing notably the energy industry, where the sliding oil price has sent yields on oil company bonds surging.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how