Cape: Heed this stock barometer

The cyclically adjusted price/earnings (Cape) ratio is far from perfect as a valuation measure. But it's certainly worth paying some attention to.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

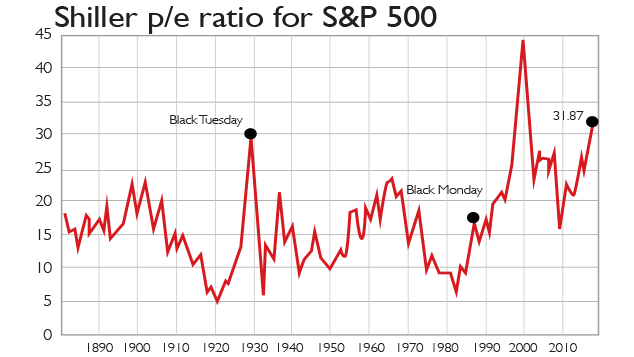

We've always been fans of the cyclically adjusted price/earnings (Cape) ratio as a valuation measure. The Cape (also known as the Shiller p/e, because it was popularised by Nobel-prize-winning economist Robert Shiller) compares the price of a market with its annual earnings, averaged over the past ten years. The idea is that this figure should be mean-reverting when market valuations swing too far to one side or the other of the long-term trend (in other words, if they become very cheap or very expensive), then they are likely to move back towards their historic average.

The Cape (used mainly with the S&P 500 in the US, but applicable to any market or even individual stocks) has scored notable successes in the past. As you can see from the chart, the Cape was at record levels in 1929 and 2000, and at elevated levels in 2007 all preceding massive crashes. However, in recent years, critics of the Cape have had plenty of fuel. The reality is that, if strictly adhered to, the Cape would have kept investors out of (or at least under-exposed to) one of the best-performing stockmarkets since the crisis. Even at the bottom of the crash, the US only very briefly fell back to its long-term average on Cape terms. In other words, post-crisis, the market never really got "cheap" and ever since, has been mostly "expensive" or "very expensive".

So what's gone wrong? One of the most-respected critics of the Cape is Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel. In an interview with Advisor Perspectives last month he outlined his main objections. As well as raising some issues about the validity of including earnings from the crash year (which can be debated), one key point he makes is that lower interest rates justify higher p/e ratios in effect, you should be willing to pay more for a given $1 or £1 of earnings if the alternative is getting next-to-nothing in a government bond or bank account. He also argues that while profit margins are high by historic standards, this is partly due to the growing importance of technology firms, which tend to have higher margins than other sectors.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That said, even Siegel now thinks the S&P 500 is at fair value and that's given prevailing low interest rates. Siegel also notes that, at the current rate of jobs growth, the US could see 3.5% unemployment within the next six months. It's unlikely that the labour market could tighten that much without driving wages up. That, in turn, will push up inflation and thus interest rates. Strong growth is good for corporate profits and share prices. But higher rates would offset that, because earnings would "have to be capitalised at higher rates, and that will definitely put a pause on the market".

So criticisms of the Cape might be fair. But it's never been pitched as a market-timing tool, and it's equally fair to say that when the next crash comes, it'll merely be the latest that has been preceded by a record or near-record Cape. We can't help but think that it's foolhardy to be fully invested now.

I wish I knew what ROE was, but I'm too embarrassed to ask

One way to look at any investment is to compare what sort of "interest rate" it is paying you, just as you would if you were comparing savings accounts. Return on equity (ROE) compares a company's post-tax profits with the money invested by its shareholders (its equity, in other words). Ultimately, you invest money in a company with the goal of seeing that investment generate a better return than you could make simply by putting it in the bank. ROE is a useful indicator of how good a company is at turning money from its investors into profitable activity.

Here's a simple example. Company A has profits of £100m and equity of £500m, giving it an ROE of 20%. That means it is probably a better quality organisation than Company B, which has profits of £200m and equity of £2bn an ROE of 10%. Equity investors are seeing their money work twice as hard in the first company as in the second, which bodes well for future returns.

However, like all such tools, ROE has its weaknesses. It can be boosted artificially by corporate borrowing (known as gearing or leverage), because debt isn't considered in this particular calculation. As a result, some people prefer to use return on capital employed (ROCE), which takes all of a company's financing into account. So in the example mentioned, Company A might also have debt of £500m meaning it is making a return of £100m on capital employed of £1bn, which gives it an ROCE of 10%. Company B might have no debt at all, meaning that its ROCE is also 10%. It is best to calculate ROCE going back at least five years, as cyclical businesses can enjoy a very high ROCE over short periods while having low average returns over the long run. A high, stable ROCE can be a sign of a very good company. Bear in mind that what a "good" ROCE is will vary between industries and sectors.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how