What’s next for the most important currency in the world?

The US dollar matters. And it has reached a turning point, says John Stepek. Where it goes next could shape the markets for months to come.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The world's most important currency has reached a potentially very interesting turning point.

Where it goes next could decide the shape of the market for the coming months.

And no, sorry, I don't mean bitcoin...

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The market likes things to be not too hold and not too cold

However, there's a fine line. The market wants the economy to keep growing if it doesn't, companies will struggle to make any profits. So growth is good. Decent economic data is good. Just as long as the economy doesn't grow so fast or inflation rise so quickly that the Fedfeels forced to raise rates more rapidly than the market can cope with.

What the market really wants is an economy with healthy, steady growth, plus a central bank that's able to take its sweet time in raising rates. One that's always lagging a good bit behind the level of growth. You might say that the market wants to have its cake and eat it - a normal economy combined with emergency-level interest rates. But given that it's been trained to expect that by global central banking policies, we shouldn't be too surprised.

Anyway, in recent months, the US economic data has been looking a bit underwhelming. On top of that, president Donald Trump's general ineffectiveness and talent for scandal have been unnerving investors too. Hopes that Trump would spend a lot of money, or cut a lot of taxes, or both, have been entirely scuppered by his inability to get anything done.

Meanwhile, the eurozone economy has been showing signs of genuine recovery after long years of misery. That's sent the euro higher. The euro is the second-most important currency in the world (after the US dollar) and as a result, the dollar has taken a bit of a pounding this year.

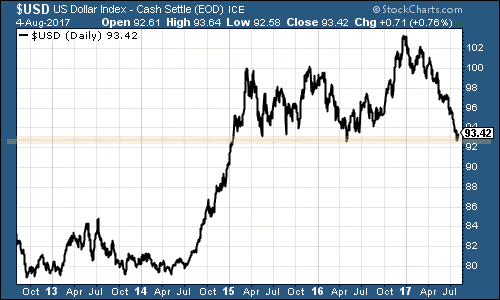

The dollar index (DXY) - a measure of the US currency against a weighted basket of the currencies of its most important trading partners has slid from a 14-year high of more than 103 in January this year to an area that technical analysts would describe as "a key area of resistance", around the 92.5-93 level.

As you can see from looking at the orange line on the chart below, all that means is that this is an area where the dollar index has previously "bounced" higher. You can debate the rationale behind this, but the upshot is that a lot of people would have been keeping an eye on this level and be getting ready to buy the dollar given the excuse.

(Source: Stockcharts.com)

As we've discussed before, the US dollar is the most important currency in the world. Put simply, it underlies global trade, which means that other countries need to swap their own currencies for dollars to keep the world going around. So when the dollar is cheap, it effectively means that monetary policy is loose for the rest of the world. And when it's expensive, monetary policy is tighter.

So the direction of the dollar matters for most global markets, and particularly emerging markets.

The relationship between the dollar and commodities has broken down

Last month, the US economy added 209,000 jobs. Markets had been expecting around 180,000. Meanwhile, annual wage inflation picked up ever so slightly from 2.4% to 2.5%.The US unemployment rate is now sitting at a 16-year low.

It wasn't a barnstorming employment report. But it was a decent one. And given that the market was starting to fret a little about the health of the US economy, it was enough to dispel the recent pall of gloom that has settled over market observers.

In short, it was a "Goldilocks" jobs report.It gives the Fed the breathing space to start "normalising" its balance sheet later this year (probably next month). But it doesn't mean rates will rise any faster, or quantitative tightening progress any more rapidly, than markets had feared.

But what does it mean for markets more broadly?

Usually, a stronger dollar would be bad news for commodities (priced in dollars). But what's interesting, say analysts at Citi, is that the negative correlation between commodities and dollars has broken down in the last couple of years.

Meanwhile, as analysts at Diapason point out, commodities are cheaper relative to equities than they have been at any point in the last 50 years, which is quite extraordinary.

For me, this suggests that from here, better-than-expected economic data may mean a stronger dollar, but also stronger demand and higher prices for commodities. As for equities, they may not like the headwind of a stronger dollar and the threat of rising interest rates.

Japanese equities, on the other hand, will probably rather like a stronger dollar, because it also means a weaker yen. That may just be the incentive they need to break out above the tight range they've been trading in for the past couple of months.

Of course, this is assuming that the dollar decides to have a prolonged rebound from here. It seems very possible, but like everything else in markets, it's hardly guaranteed. It's one to keep a close eye on.

(I update on the dollar every week in MoneyWeek Unlimited, our weekly subscriber-only email. If you'd like to receive it, subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine and you'll get it automatically).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Could Chinese investments race ahead in the Year of the Horse?

Could Chinese investments race ahead in the Year of the Horse?As the Year of the Horse begins, we highlight the trends and sectors that could make great Chinese investments for the coming Lunar year

-

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?With gold and silver prices having outperformed the stock markets last year, mining stocks can be an effective, if volatile, means of gaining exposure