The Trumping of the rent-seekers

Trump’s assault on vested interests won him the White House. Now we must see if he will grab the opportunity to really make America great again, says Edward Chancellor.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Donald Trump's victory couldn't have come about but for a sense that America's elites were taking an ever larger slice of the economic pie a pie which was no longer expanding at its usual rate. The president-elect successfully campaigned against vested interests on Wall Street, corporate America and in Washington who share responsibility for the declining vitality of the economy. What's harder to predict is whether a Trump administration likely to be peopled with many Wall Street veterans will actually fulfill its campaign promises and avoid falling prey to other special interests.

The economic historian Barry Eichengreen suggests that American populism arises when the public believes that the mainstream parties have been captured by special interests. Populism which flourished after periods of rising inequality in the 1890s, and reappeared during the Great Depression represents "anti-system thought", says Eichengreen. The current US "system" has delivered weak economic growth and increasing inequality. History repeats itself, the main difference being that this time the nativists have got their man into the White House.

A framework for understanding this phenomenon is provided by the late University of Maryland political scientist, Mancur Olson. In The Rise and Decline of Nations, (published in 1982) Olson argued that economic growth wanes when groups of rent-seekers, or what he called "distributional coalitions", predominate. By definition, rent-seekers aim to snag a larger slice of the economic pie. The real cost of their activities, Olson argued, is economic stagnation.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Olson identified a societal conundrum. There's little incentive for individuals to organise to pursue the public good, he posited, since everyone shared in the benefits. By contrast, small groups are better at organising to pursue their own selfish ends. This problem becomes accentuated with the passage of time: "Stable societies with unchanged boundaries tend to accumulate more collusions and organisations over time," he wrote.

Olson's distributional coalitions belong neither to the political left or right, but comprise an assorted mixture of the political elite, unions, bureaucrats and business interests. They favour complex regulation, which restricts new entrants and protects existing rents. Distributional coalitions also develop an ideology to protect the status quo. A widening gap between the very rich and everyone else is a sign that special interest groups are in control: "There is greater inequality in the opportunity to create distributional coalitions," wrote Olson, "than there is in the inherent productive abilities of the people." The main problem, however, is that they produce "growth-retarding regimes."

Were Olson, who died in 1998, around today, he would surely have described the current state of American society, and the appearance of what economists have called "secular stagnation," as the consequence of a network of narrow distributional coalitions.

First, there's a corporate elite which prefers financial engineering to capital spending, because it boosts share prices and allows them to cash in on outsized equity-linked compensation packages. Such activities are growth-destroying. It's telling that not a single Fortune 100 chief executive publicly backed Trump.

Then there's Wall Street, which earns large fees from leveraging the corporate sector, and feasts on all manner of tax loopholes that reward capital over labour. Again, the property mogul found surprisingly little support from the financial services industry in his White House bid. Let's not forget the Washington politicians who, through an institutionally corrupt-if-legal campaign finance regime, proffer access to their offices in exchange for contributions to their political races.

President Barack Obama's administration didn't attack these vested interests. Wall Street's bonus culture continues essentially unchanged under his watch. No senior bank executives were jailed for the shenanigans which contributed to the Lehman Brothers debacle. Instead, the banks' hapless shareholders have been hit with tens of billions of dollars in fines. To make matters worse, Obama has added a new thicket of banking regulations, as represented by the 30,000-odd pages of the Dodd-Frank Act; thereby creating another bloated class of bureaucratic rent-seekers who, by many accounts, have undermined the provision of credit to Main Street. Corporate pay excesses have continued post-Lehman.

Nor has Washington's money culture changed. The cost of Congressional elections has risen inexorably, making legislators ever more dependent on donors and lobbyists. Tax-advantaged foundations and top universities have continued to provide the ideas and policies which support today's distributional coalitions, while leaving the sources of rent extraction largely unexamined. Revolving doors link the Ivy League universities to Washington and Wall Street. Witness the glorious career progress of Ben Bernanke from his tenured position as head of the Princeton economics department to chairman of the Federal Reserve, and onwards to his current role as a think-tank pundit and hedge fund advisor.

At the Fed, Bernanke's unconventional monetary policy delivered the asset price inflation upon which today's distributional coalitions feed. But it also produced the weakest economic recovery on record, together with the inevitable surge in inequality. In the years after the financial crisis, the middle classes saw their wealth collapse by nearly 50%, while the rich escaped relatively unscathed, according to NYU economist Edward Wolff. It's hardly surprising, then, that large swathes of the public believed Trump's message that the system was rigged.

During the course of his campaign, Trump incessantly attacked distributional coalitions. He swiped both at the behaviour of Wall Street and also at the new financial regulations and business regulation in general. Trump alleged that the Fed's interest-rate policy was politically motivated. He accused the universities of political correctness and threatened the tax advantages of foundations. And Trump ceaselessly bludgeoned "crooked Hillary" for being in bed with Wall Street, while accusing the Clinton Foundation of operating a "pay-to-play" racket, in which charitable activities, personal interests and the pursuit of political influence were inextricably interwoven.

Trump's assault on these vested interests won him the White House. If the Lehman bust presented a "Minsky moment" (named after the economist Hyman Minsky who argued that financial stability was in itself destabilising), Trump's victory provides an "Olson opportunity" dare one say it to make America great again.

Still, Olson might not have approved of Trump's agenda let alone, the bigotry and boorishness on display during the campaign. Olson warned that protectionist policies, as proposed by president-elect, are invariably favoured by rent-seekers. He would also have noted that Trump's planned infrastructure splurge provides yet more opportunities for skimming. Moreover, as word trickles out from the Trump transition team of possible cabinet appointments for former executives of Goldman Sachs, KKR and other Wall Street types hopes for genuine systemic reform may prove fleeting.

Yet, at heart, Olson was an optimist: "it takes an enormous amount of stupid policies or bad or unstable institutions to prevent economic development." If - and that's a big IF - Trump were to succeed in assaulting the "growth-retarding" forces within American society, he could well end up surprising his legions of right-thinking critics.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

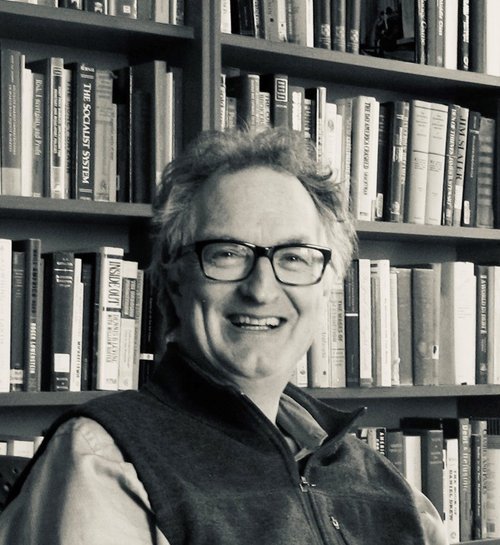

Edward specialises in business and finance and he regularly contributes to the MoneyWeek regarding the global economy during the pre, during and post-pandemic, plus he reports on the global stock market on occasion.

Edward has written for many reputable publications such as The New York Times, Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo, The Spectator and he is currently a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He is also a financial historian and investment strategist with a first-class honours degree from Trinity College, Cambridge.

Edward received a George Polk Award in 2008 for financial reporting for his article “Ponzi Nation” in Institutional Investor magazine. He is also a book writer, his latest book being The Price of Time, which was longlisted for the FT 2022 Business Book of the Year.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how