Has Mario Draghi called the top of the bond bubble?

The ECB's Mario Draghi has issued a warning to bond buyers. It's just one more reason for investors to tread very carefully in the bond markets, says John Stepek.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Bunds German government bonds have been attracting an unusual amount of attention in recent months.

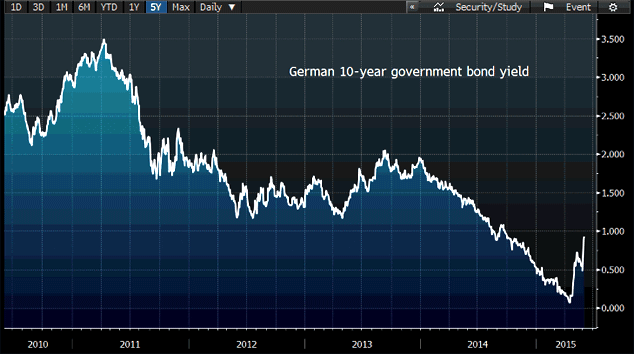

Yesterday, Germany's cost of borrowing hit its highest level since last October. Lenders are now demanding a whopping 0.89% or so to hand their money to the German government.

Yes, I know what you're thinking big deal, you'd love to bag a ten-year mortgage at that rate.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

But this matters more than you might think. Here's why.

The trouble with bunds

And this morning it's just carried on higher. The chart below of the German ten-year bund yield over the past five years shows just how sharp the jump has been.

We've talked about why this is worth watching before, but let's have a quick reminder. Bonds are currently very expensive; that's partly because there's been a big, price-insensitive buyer in the market central banks.

When bond prices rise, yields fall. When yields fall, the cost of borrowing goes down across the economy.

Problem is, bonds are now so expensive that it's increasingly difficult to see how yields can go a lot lower before you get into a very strange world indeed. It is certainly possible for bond yields to turn negative (and many have).

But at those levels they are pricing in either a lot of deflation (which we don't yet have), or a world where central banks never stop printing money (which seems a more likely potential outcome, but still not necessarily the case).

When prices reach bubble levels and I think it's reasonable to describe the bond market as bubbly they have a tendency to fall hard when they do fall. In the case of the bond market, a proper crash could rapidly drive up borrowing costs in markets across the world.

In a world laden with debt, that's not likely to result in a happy ending.

So when you see bond yields spiking and therefore, prices plunging at the rate they just did, it's worth paying attention. Even if the move in yields sounds very small. At the end of the day, it only takes a pebble to start an avalanche.

Of course, the abiding narrative is that central bankers will always come to the rescue. And investors were hoping yesterday that Mario Draghi might make some comment on the recent volatility in yields, when he stood up to give his usual press conference on the European Central Bank's latest monetary policy moves.

He did make a comment. It went something like: "Tough. Get used to it." No wonder bonds sold off.

Mario Draghi's great big bluff

Few of the world's central bankers have a genuinely tough job. Almost no government on earth is going to complain if you cut interest rates, and voters generally like it when money gets cheaper. So there's a natural bias towards cutting rates and propping up markets.

Draghi is different. As the head of the ECB, he has to balance the demands of several different governments, the most important of which Germany has an atypical fondness for relatively hard' money. There's also a wider continental distrust of the financial sector so the health of the stockmarket doesn't enjoy the same primacy as in say, the US.

That all adds up to a very tricky balancing act. As a result, he's become an expert at manipulating the market's expectations, while keeping the politicians at his back relatively happy.

Surprise is the most powerful weapon a central banker has. The whole point of central bank intervention is to change the direction of a market. If the market already thinks it knows what you're going to do, then that'll be priced in. So if you want to shift the market, you have to do something else.

This is what Draghi spends most of his time doing. For a while there, it looked as though he'd never get quantitative easing (QE) off the ground so instead he turned his focus to manipulating the euro lower, by daring currency speculators to call his bluff, and burning them every time they did.

As a result, he managed to keep a lid on the single currency until he finally managed to get QE past the Germans. This is all while attempting to keep the Greek crisis from bubbling over. It's been a positive masterclass in political poker playing.

And this is what you need to remember when you read his comments on bond markets.

Central bankers aren't stupid. They have no idea how they're going to get out of this mess they've created. The further bonds go into bubble territory, the more painful the fallout will be. So he wants investors to exercise restraint; he wants them to tame their irrational exuberance.

But equally, there's no way that Draghi is going to reverse QE and stop buying bonds, having finally got the Germans to agree to it. So the fundamental driver of the bond bull market isn't going to be taken away.

So he does what he can he talks the market down. Here's what he said yesterday: "We should get used to periods of higher volatility. At very low levels of interest rates, asset prices tend to show higher volatility."

As a result, investors are reconsidering the idea that they can rely on a free lunch by flipping bonds.

Has Draghi marked the top of the bond market?

At the end of the day, bull markets die because they run out of buyers. That means that the bond bubble can continue for as long as central banks are still doing QE (as my colleague Merryn pointed out recently).

However, this looks like Draghi is drawing something of a line in the sand. He's issued a big buyer beware' warning here. When he did that for the euro at around the $1.40 level, that marked a top.

He might have to reconsider those words if markets take him too seriously. He wouldn't want to see a bond market crash. But a gentle unwinding to slightly less lethal levels? I can imagine he might tolerate that.

It's all another good reason to be very careful with the level of bond exposure in your portfolio. Central banks are walking a very narrow tightrope here, and history shows that they're prone to slipping. James Ferguson of the MacroStrategy Partnership wrote more about the potential fallout from a bond bubble in a recent edition of MoneyWeek magazine subscribers can read the piece here. (If you're not already a subscriber, get your first four copies free here.)

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how