A nasty surprise lurks in government bonds

Cris Sholto Heaton explains what will happen in the bond markets once central banks begin to raise interest rates.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The performance of "risk free" government debt ie, bonds from countries such as the US, the UK, Germany and Japan that have high credit ratings are largely determined by the outlook for rates. Bonds that mature in thenear future take their cues fairly directly from short-term interest rates set by central banks. Longer-term bonds are affected by how investors expect rates to change in the years ahead, rather than their level today.

Let's assume that investors expect UK interest rates to rise from around 0.5% to around 2% over the next two years, but think that this will be a short-lived cyclical rise and average rates over the longterm will remain relatively low.

In that case, yields on ten-year gilts might go up relatively modestly (let's say 0.5 percentage points) even when short rates start rising. This means that the "yield curve" the chart of yields across different bond maturities will become flatter (meaning the difference between yields on short-term bonds and long-term bonds will get smaller).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

On the other hand, if investors conclude that the era of low interest rates is firmly over and rates are likely to be higher than expected in the future, yields on longer-term bonds will rise (in our example, let's assume they go up by 1.5 percentage points). So in this case, the yield curve will get a bit flatter (because short-term rates are up the most), but it will shift significantly upwards (because interest rates of all maturities have gone up).

Spreads could get wider

So what happens to yields on these bonds depends not just on how interest rates change, but on changes in the spread.Thus if ten-year government bond yields rise by 0.5 percentage points, but yields on corporate bonds of similar maturity rise by just 0.1 percentage points, the spread narrows ("compresses").If corporate bond yields rise by0.75 percentage points, thespread widens.

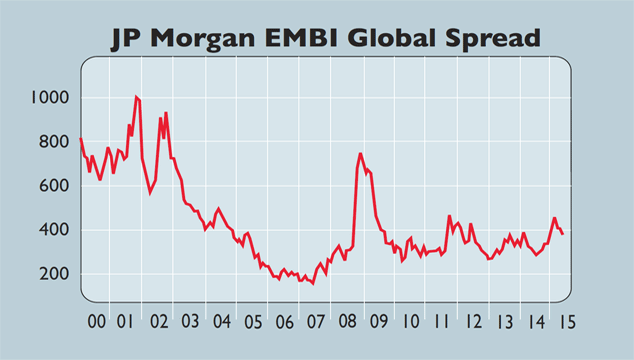

So what are spreads more likely to do? If we look at them in the context of recent history, it seems like they have scope to shrink. The spread on the JP Morgan EMBI Global index, which tracks dollar-denominated emerging-market bonds, is currently around 360 basis points (3.6 percentage points one basis point equals one-hundredth of a percentage point). It's been lower than that several times in the past five years, and was less than 200 basis points before the global financial crisis. The pattern is similar for corporate bonds, especially the riskiest "high yield", or "junk" bonds.

However, spreads are not exceptionally generous by longer-term standards (see chart above). And investors should consider what might cause spreads to widen. In theory, spreads are mostly driven by how likely the bonds are to default. However, factors such as liquidity also play a part; corporate bonds and emerging-market bonds are less liquid, so investors should demand a premium to hold them.

This is emerging as a major worry for bond investors, especially given the potential for investors who have piled into riskier bonds in the hunt for yield to rush for the exits once they can earn an adequate return on safer assets.

So investors who are betting on narrower spreads to offset the impact of higher rates could get a nasty surprise.

What will happen next?

The great difficulty in anticipating what will happen to credit once rates begin rising is that today's market looks so different to previous cycles. Not only has quantitative easing distorted markets since the crisis, but lax central-bank policies before 2007 created very favourable conditions for borrowers.

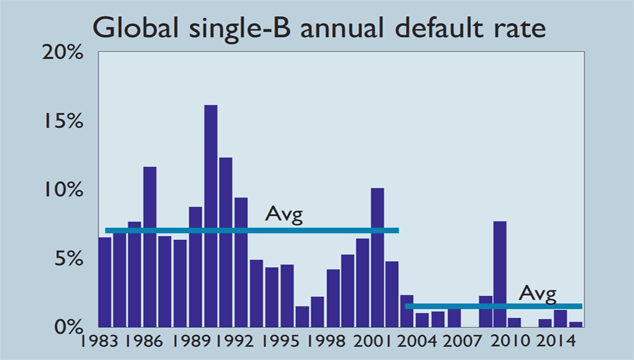

Hence while defaults on bonds with a rating of B averaged 6.9% per year from 1983 to 2002, they've averaged just 1.5% since. If defaults were to stay low, current credit spreads don't look like a recipe for disaster. But if defaults rise back towards historic averages, it would be a different matter.

If we assume a 5% average default rate and a 40% recovery rate on defaults, that would cost investors 3% per year. The spread for B-rated bonds is around 360 basis points (against a 20-year average of 570), implying investors would earn little extra return after losses.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson