Should investors chase growth or hunt value?

Should you try to invest in countries that are likely to see high GDP growth, or in markets that are cheap?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The question of whether countries that have higher growth tend to have higher investment returns over the long term is a hotly contested one. Studies come to different conclusions: the answer seems to depend on which countries you look at, the time period involved, whether you consider inflation-adjusted returns for local investors or foreign-currency returns for international investors, among other factors.

However, over the shorter term, the picture seems clearer. Studies suggest that, over periods of a few years, countries with the best GDP growth prospects tend to offer higher returns certainly once currency movements are taken into account.

For example, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of London Business School looked at the performance of emerging markets from 1976 to 2013*.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

They found that stocks in countries whose growth was in the top 20% of countries over the following five years outperformed those in the bottom 20% by more than ten percentage points per year an enormous premium. Other studies show similar but smaller effects for developed markets.

The problem here is that this is based on future growth. That's great if you have perfect foresight, but for those of us who aren't soothsayers, it's rather dangerous. Why? Because when we're trying to guess which countries will post the strongest growth in the future, our judgement will be biased by which ones have grown most strongly in the recent past. And studies have also found that investing in the countries that have been growing strongly tends to be a recipe for underperformance.

Dimson, Marsh and Staunton found that stocks in the 20% of emerging markets with the strongest growth over the past five years went on to underpeform those with the weakest growth by more than ten percentage points per year. Again, a similar but smaller effect seems to be present in developed markets.

Why does this happen? It's down to two factors. First, investors get too excited about countries that have delivered good growth in the recent past and push up stocks until they are too expensive, meaning that they are likely to deliver weaker returns in future. Second, because economies are cyclical, those that have grownexceptionally strongly for the past five years are quite likely to slow down and be weaker performers over the next five years, just as investors flood in.

Value, not growth

The evidence suggests strongly that it does. For example, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton found that investing in stocks from the 20% of emerging markets with the highest dividend yield outperformed a strategy of investing in the 20% with the lowest dividend yield by more than 20 percentage points per year roughly twice the premium from being able to predict future growth perfectly. Once more, other studies suggest the same is also true to a lesser extent for developed markets.

Not only has the outperformance from selecting countries based on value comfortably beaten the outperformance from selecting on future growth, but a value strategy is considerably more useful. While we can only attempt to estimate future growth, the current dividend yield is known and easy to obtain. That makes a value investing strategy far more relevant to real-world investing.

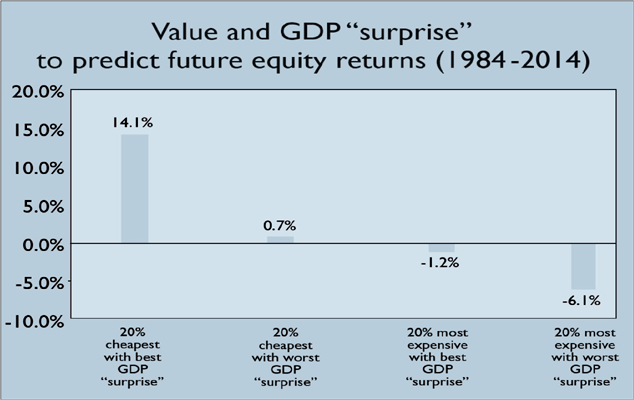

The last question is whether there is any way to put these two effects together. If we know that countries that grow well tend to outperform and those that are cheap tend to outperform, what happens when countries are cheap and subsequently grow more strongly than expected?

or better still, both

This handily beats the gain from just picking the cheapest countries (3.2 percentage points), or those with the best growth (2.6 percentage points). What's more, even the group of cheap countries with the worst GDP surprises those that grew slower than expected still slightly outperformed the average country, by 0.7 percentage points per year.

So the obvious conclusion is that if you're going to try to pick countries that are likely to grow well, make sure they're also relatively cheap. If you get both calls right, history suggests that you should do very well. If you end up with too many slow growers, the cheap valuations still give you scope to do okay. Conversely, buying expensive markets is likely to bring disappointment, regardless of whether you guess right on growth or not.

*Emerging Markets Revisited, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton, Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2014

**Ditch the Good, Buy the Bad and the Ugly, Ben Inker, GMO Quarterly Letter Q4 2014

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn