Five threats to your wealth

The threat of Greece leaving the eurozone has investors feeling jittery. But it’s far from the only big risk out there. John Stepek looks at the top five.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

At a time when most asset classes from stocks to bonds look expensive, the threat of Greece leaving the eurozone has investors feeling jittery. But it's far from the only big risk out there. John Stepek looks at the top five.

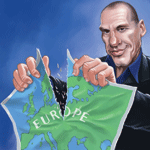

Grexit

You're probably aware of Greece's woes by now. In a nutshell, Greece has too much debt. Athens wants it to be cut, and it wants to ditch austerity, imposed on it in exchange for emergency help from the rest of Europe. The rest of Europe led by Germany has so far been reluctant to comply.

Most people still assume a deal will be made another dollop of euro-fudge to keep the show on the road. But as Brian Dennehy of FundExpert.co.uk points out, they may have read it wrong this time.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

If Greece wants to reduce its debts and abandon austerity, the quickest way to do so is to leave the eurozone. That won't be painless, but it does mean Greece gets its sovereignty back and can print as much money as it likes. And Germany can draw a line under a festering sore, created by a nation that technically shouldn't ever have been allowed to join the eurozone anyway.

Under this scenario, the whole negotiation is just a face-saving exercise to allow both sides to say they tried their best, but that they have to stand up for their voters' interests. A majority of Greeks still want to keep the euro though fewer than before the last election.

But "intransigence by the rest of Europe and the troika will create a smokescreen behind which Greece can exit... The Greek voters will sense that their government has made a reasonable proposal, rejected by the nasty Germans," notes Dennehy. That sense of reclaiming national pride will help them endure the short-term chaos of an exit. So a "Grexit" is certainly not out of the question.

What would happen next? The optimistic scenario is that the European Central Bank prints enough money to stifle market panic, and in the short term Greece suffers enough visible economic pain to discourage Spanish voters from following suit, stopping any domino effect in its tracks. In the medium term, Greece recovers as tourists and investors flock to what is suddenly the cheapest country in Europe (and anyone who invests just after a Grexit makes a fortune). Sounds good.

But you can paint far bleaker scenarios. Say Greece leaves. Everyone hopes "contagion" can be contained. But as Lehman Brothers showed, a bank doesn't have to be big to be important. The eurozone's monetary plumbing is complicated can we be sure that knocking out the entire Greek banking system wouldn't have wider consequences? Or say Greece gets what it wants the debt is cut and Europe goes easy on it. That's a greenlight to other nations to vote for their own Syrizas.

Spain led by Podemos would be next in line for debt relief and austerity reversal. Then Italy in short, a whole string of crises focused on much more important nations. Even the "fudge" is not necessarily a benign solution. The problem with past European fudges is that they leave the issue unresolved. We'd only end up revisiting this story yet again in another year or so.

War

Of course, a Grexit is not the only headline-grabbing worry. You'll be hard pushed to find a time when the world has been at peace. But the surreptitious war in Ukraine, with Russian-backed rebels destabilising the government and taking territory, points to a far riskier geopolitical picture than we've seen since the Cold War. For example, Nato warned last week that it was forced to intercept Russian planes in European airspace more than 400 times last year up fourfold on 2013.

The skirmishes in Ukraine themselves have so far had little tangible impact on wider markets (and Russia's recent woes have been as much to do with falling oil prices as with sanctions). But any significant escalation would, of course, rattle markets badly.

Perhaps more subtly, a return to a more polar world would reverse many of the gains we've seen from globalisation in recent decades. For example, where countries and companies start to emphasise security of supply over costs, we could see a scramble for resources, and a reduction in offshoring, both of which are potentially inflationary while being bad news for global trade.

China's slowdown

Of course, a bog standard recession led by China's slowdown is also bad news for global trade. In fact, hedge fund manager Crispin Odey reckons that what we might be seeing now is "the first experience of a business cycle since 2008". The trouble is, investors have so much faith in central bankers these days that they "do not believe we can experience such a downturn".

Odey's point is that "we are really at a dangerous point to try to counter the effects of a slowing China, falling commodities and emerging-market incomes, and the ultimate First World Effects... If economic activity, far from picking up, falters, then there will be a painful round of debt default." He reckons that central bankers have effectively used up all their monetary firepower, with only weakening their currencies remaining as a viable option.

Currency war

That in turn helps to explain the current rolling currency devaluations also known as "currency wars". The striking chart below, from David Woo at Bank of America Merrill Lynch (and republished by David Keohane of FT Alphaville), shows that currency-market volatility is currently at its highest level in 20 years, barring two big exceptions the Asian crisis of 1997 and the Russian bust in 1998, and the 2008 credit crunch following Lehman Brothers' collapse.

That's no surprise. The Swiss recently shocked markets when they stopped artificially holding the franc down against the euro. Since then, the Danes have been frantically slashing interest rates to hold the Danish krone down too, as investors bet on it strengthening.

They're not alone in hoping to keep their currencies weak: Egypt has relaxed its own peg to the US dollar it is now more worried about maintaining competitiveness, than about potential inflation. And you've got the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan printing money to weaken the euro and yen.

Having a weaker currency helps exporters and boosts inflation. But not everyone can have a weak currency at once currencies have to rise or fall relative to one another. And so, Woo argues, this is a zero-sum game that merely boosts foreign-exchange volatility, which in turn makes it more expensive to sell goods overseas (because of the expense of hedging against unpredictable, hefty currency movements).

To back up this view, he notes that in the past, during periods of high currency volatility, global trade has tended to slow down. That, says Odey, matters even more today, given world trade has risen "from 12% to 32% of world GNP in little over 20 years".

If Woo is right, competitive devaluation simply erodes trust and increases trading costs hurting economic growth. Under this scenario, you end up with a similar outcome to the 1930s when rising trade barriers and competitive devaluations contributed to the collapse in growth.

The bond bubble bursts

However, US economist Barry Eichengreen is less gloomy. He points out on FT Alphaville that central banks are being far more proactive and experimental than in the 1930s, and that with "sufficiently aggressive monetary action and supportive fiscal steps, policy can produce results even in this environment". But if central banks do succeed, it could leave us with our biggest problem of all the puzzle of bond yields.

Everyone seems to be worried about deflation right now to the point where they are willing, in many cases, to accept negative yields on bonds. In other words, assuming the bond is held to maturity, they'll make a guaranteed loss (in nominal terms at least). There's often an assumption that the bond market is "cleverer" than other markets. So one interpretation for these bond yields is that deflation is indeed coming.

But it's also perfectly possible for a bubble to have formed in bonds, as Robert Shiller hints in our interview with him. There's a good story there we have a "new paradigm" in the form of "secular stagnation" and the "new normal" of low or no growth.

We have price-insensitive buyers a "wall of money" in the form of central-bank money printing and forced buying by banks requiring "safe" assets.

And yet, while we are seeing mild deflation in the eurozone, and disinflation in many other areas, there's no guarantee that this will continue. The US just reported its strongest wage growth in six years in a very healthy employment report for January. In the UK, David Cameron is putting pressure on businesses to drive through pay rises too. And central banks in most major economies are hellbent on creating inflation.

Inflation is toxic for bonds, and all the more damaging when they're as highly priced as they are now. Make no bones about it a "disorderly" sell-off in the bond market could be brutal. In previous bond-market crashes, investors have been compensated by high yields losing 10% of your capital value in a year isn't as painful when you've received a coupon payment of 7% that same year.

But dropping 10% is a lot worse when your yield was already negative and you had considered your investment "safe". Moreover, crashing bond prices would drive up interest rates. For a world that's still very heavily indebted, as McKinsey has pointed out, that could be disastrous for everyone from consumers to companies.

Let's be careful out there

It's a gloomy road map we've laid out and maybe it won't all come true. But if it does, how can you safeguard yourself? For more on what you might want to buy, David C Stevenson (usually a bullish sort of fellow) has ideas on protecting your portfolio from a nasty crash.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.