Is your fund a ‘closet tracker’?

Many funds are ripping off investors by being actively-managed in name only. Cris Sholto Heaton explains how to tell if your fund is one of them.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

One of the fund industry's dirty secrets is that large numbers of actively managed funds aren't doing what they claim. Instead of trying to beat the market, their managers quietly set out to make sure their returns will never be too far away from their benchmark index.

Yes, they'd like to do a bit better if they can, but their top priority is to ensure that they don't lag too far behind.

From the perspective of the fund companies and their managers, this 'closet indexing' or 'benchmark hugging' is entirely understandable. Investors are likely to pull money out of funds that do significantly worse than the market.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Since most fund companies aim to maximise the amount of assets they manage because they earn higher fees that way they're keen to avoid outflows.

So managers can come under considerable pressure if their returns fall much behind their benchmark, even for a couple of quarters. The easiest way to avoid that happening and keep their jobs is to become a closet indexer.

But while it may be understandable that they do that, it's also unacceptable. People buy active funds in the expectation that they will try to outperform. If they simply want to earn the market return, they can buy a passive tracker fund, which will be far cheaper than an active fund.

Charging fees for active management while doing otherwise, because you're not confident that you can outperform or because you're not sure your investors will stay the course for long enough for your bets to come good is entirely unfair.

Getting worse

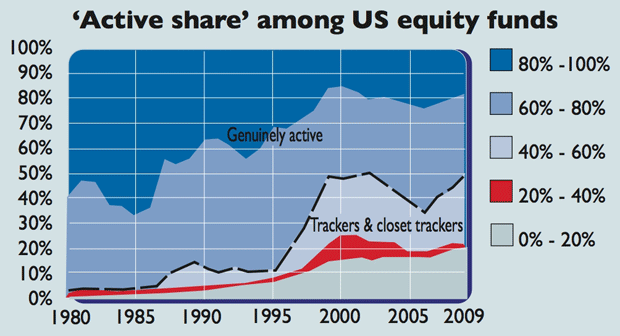

So how prevalent is this practice? One way to look for closet indexing is a metric called 'active share', developed by US-based researchers Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto. In simple terms, active share measures the percentage of the fund's portfolio that differs from the fund's benchmark index.

For a fund that uses no leverage or shorting, active share will vary between 0% for a pure index fund and 100% for a fund that has nothing in common with its benchmark index.

While 100% usually isn't a good thing it suggests that the fund isn't investing at all in the type of stocks it's being measured against a low share tells us that the fund is indulging in some indexing, whether it claims to be or not.

Cremers and Petajisto set the cut-off for a closet indexer to be an active share of less than 60% and measured the evolution of active share among US equity funds over time. The chart belowshows the results.

As you can see, the proportion of funds with an active share above 60% has declined steadily, while that with an active share in the 40%-60% range has increased.

In other words, closet indexing has become far more common over time, perhaps due to the increasing short-termism of the investment industry. On the plus side, you can also see the significant increase in the number of funds with active share less than 20%.

This is due to the growing popularity of genuine low-cost indexing, that is, people putting their money in funds that simply track certain indexes a trend that's been good news for investors.

High costs

These results tell us that many fund investors are paying for more active management than they're getting. But how much are they overpaying by? The simple answer might seem to be to compare the cost of a closet indexer with that of a true index fund.

So, if a FTSE 100 fund has a total expense ratio (TER) of 1% and an exchange-traded fund (ETF) tracking the FTSE 100 costs 0.3%, investors are paying 0.7 percentage points more. But that approach is too generous to the worst closet indexers, since it makes no allowance for how much indexing is actually going onin each fund.

That's where a study by US investment consultant Ross Miller comes in. Miller uses the correlation between the performance of a fund and the performance of its benchmark index, the fund's TER and the TER of an equivalent index fund to calculate a measure called 'active expense ratio'.

Put simply, this method calculates how much investors are paying for the amount of active management that shows up in the fund's returns, assuming that they should rationally just pay index fund-fees for the part of the returns that simply matches the index.

Applying this approach to a sample of 731 US large-cap equity funds, Miller found that the average fund had an active expense ratio of almost 6.5% in the period 2000-2009, compared with a headline TER of just 1.2%.

As he points out, this implies that the average investor in these funds is paying hedge fund-like fees relative to the amount of active management they get.

Getting rid of indexers

Most research on this topic has focused on US-based funds, but there's no reason to believe that the UK is any better. Just as many investors in the UK are holding closet indexers and paying dearly for the privilege. If you're one of them, there are two approaches you can take to eradicate them from your portfolio.

One is to replace expensive active funds with cheap trackers. That makes sense since most active managers fail to beat the market over the long term. The other is to find the small minority of funds that are both genuinely active and likely to outperform at the same time.

Interestingly, Cremers' and Petajisto's work suggests that managers with high active share, concentrated portfolios and strong past performance are much more likely than most others to do well.

However, successfully choosing active managers is still a task that's easier said than done. So, investors who are unable or unwilling to put in a large amount of work up front will be better off optingfor tracker funds.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

Properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence