What Warren Buffett’s favourite valuation ratio says about markets today

There's no simple model of investing that can tell you where and when to invest. But there is one ratio that can help decide whether now is a good time to invest heavily in a market. Ed Bowsher explains what it is.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When I first started investing, I was a bit like an earnest teenager looking for the meaning of life.

I was convinced there had to be a secret' to successful investing. Surely there was a simple model that could tell me where I should invest my cash, and when I should do it?

Experience has taught me that investing is rarely that straightforward. All of the well-known investment ratios have their flaws and can be misleading at least some of the time.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

However, some are better than others. There's the cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio, for example, which is one of our favourites at MoneyWeek. But it's not the only one.

In fact, if I was only allowed to use one ratio ever again, there's another I'd be very tempted to use which also happens to be one of Warren Buffett's favourites

Warren Buffett's favourite investment ratio

The ratio I'd like to discuss today is stock market capitalisation to GNP.' As you may have guessed, this ratio tells you whether the combined value of a country's stock markets is worth more or less than its annual economic output.

Clearly, this ratio can't tell you whether or not you should buy shares in a specific company. But it can be useful in deciding whether now is a good time to invest heavily in a market, or if you'd be better off holding back.

So what's the rationale behind this ratio? Let me leave it to Warren Buffett, who in 2001, noted that it had predicted the bursting of the tech bubble:

"The market value of all publicly-traded securities as a percentage of the country's business that is, as a percentage of GNP is probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment. And as you can see, nearly two years ago [1999] the ratio rose to an unprecedented level.That should have been a very strong warning signal."

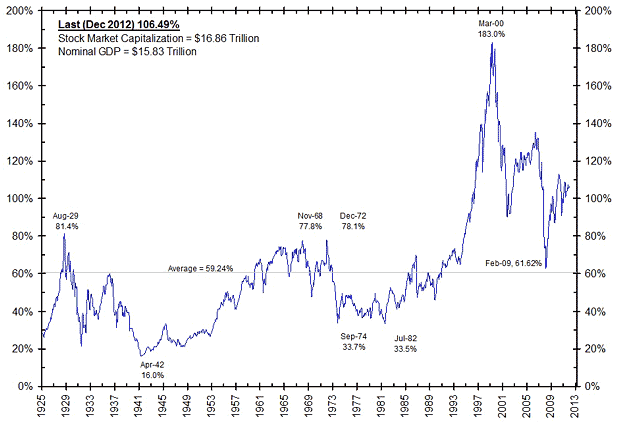

Indeed in March 2000 the very peak of the tech bubble - the ratio reached an all-time high in the US. The Wilshire 5000 stock market index was worth 183% of US GNP.

That was hugely out of whack with history. As you can see from the chart below, this ratio (in the US at least) has been below 100% for most of the time since 1925.

Stock market capitalisation as a percentage of US nominal GDP

Source: Bianco Research

You can also see from the chart that the ratio went as low as 61% in February 2009. So it has highlighted good opportunities to buy as well flagging up times when the market was grossly overvalued.

Right now, the figure stands at 111.9%, according to Gurufocus.That suggests that the US market is currently overvalued, but not in a ridiculous bubble. Which is pretty much what I said in this article.

Can we use this ratio outside America?

Some people argue that you can use the ratio to value lots of different markets very quickly. Using this approach, if a country's stock market/GNP ratio is around the 50% mark, it looks very cheap. If the ratio is over the 100% mark, it looks expensive.

This approach broadly seems to work in the States. But I think it's dangerous to transfer it directly into other markets. The UK is a great example of how the ratio can be misleading. Right now, the ratio for UK market is 129%, suggesting it is more expensive than the US. But I don't think that's a fair reflection of the UK, which on many other measures is a good bit cheaper than the US.

Remember that many FTSE 100 companies do most of their business outside UK. In fact, roughly two thirds of the profits generated by all the FTSE 100 companies are earned abroad. So it's no surprise that Britain's total stock market valuation is a significantly higher than GNP. These aren't UK-focused businesses.

But that doesn't mean the ratio is useless. Instead of comparing the stock market/GNP ratios between markets, it makes more sense to compare a single market to its own history. At 129%, the UK is currently about halfway between its historic low of 47% and its peak of 205%. So it's not cheap, but it's hardly grossly overvalued either.

What about other markets?

I've used this ratio once before here, when I wrote that China's future may be brighter than anyone can expect'.

At the time, China's stock market/GNP ratio was 48%. Looking at the market's own history, the historic low for China is 45%. That's a strong buy' signal if ever there was one.

Even then, I would never have suggested that anyone invest in China purely due to this ratio. The historical data for China's markets is still quite short compared to the US.

But when you can see other positives in a market, this ratio can be very handy in helping you make a decision. And that low ratio is just one of the reasons why I've been enthusiastic about China recently. Subscribers can read more on the case for China here. If you're not already a subscriber, subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine.

Our recommended articles for today

How I learned to stop worrying and love fracking

Bengt Saelensminde explains why he's in favour of the controversial gas drilling technique, and how he's thinking of playing the sector.

How takeovers work

Ed Bowsher explains at how company takeovers work, and whether private investors can make money from them.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Ed has been a private investor since the mid-90s and has worked as a financial journalist since 2000. He's been employed by several investment websites including Citywire, breakingviews and The Motley Fool, where he was UK editor.

Ed mainly invests in technology shares, pharmaceuticals and smaller companies. He's also a big fan of investment trusts.

Away from work, Ed is a keen theatre goer and loves all things Canadian.

Follow Ed on Twitter

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how