How can you tell if a stock is cheap?

In seeking the best-value stocks, you may not think to use this lesser-known, yet successful ratio. Tim Bennett explains what it is, how it works, and where it's telling you to put your money.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

How do you make money in the stock market? The glib answer is to buy low and sell high': buy stocks when they're cheap and cash in when they get expensive. But how do you tell when something is cheap enough?

There are lots of ratios you can use, from price/earnings to price/book. But a recent study by analysts Thomson Reuters StarMine points to a less well-known measure: price/intrinsic value (p/IV). Buy when a market is cheap on this measure, and history suggests you could earn double-digit returns for years. So how does it work?

What is intrinsic value?

A company's intrinsic value is derived from the dividend discount model (DDM). Without going into all the gory technical details, the DDM takes the expected annual dividend for the year ahead and then applies an estimated growth rate for future dividends (this takes into account inflation and the fact that as earnings grow, so too should the dividend payouts).

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So you get a rough idea of your expected future income. A discount is then applied to compensate for the investment risk. You arrive at the discount rate by subtracting the dividend growth rate from the total rate of return you'd expect an investor to need in order to take the risk of buying the company in the first place.

It's a little like valuing a house by looking at the future rental income you expect to get, then reducing it in order to compensate for the risk of investing in property as an asset.

Here's an example. Say a firm's next dividend is £2m, the expected dividend growth rate is 5% and the minimum return demanded by shareholders for investing in this firm (as opposed to safer bonds or even cash) is 8%. The intrinsic value is: (£2m x 1.05)/(0.08-0.05), or about £70m.

Now let's say the firm's current market capitalisation (the number of shares in issue multiplied by the share price) is only £50m. The p/IV ratio is £50m/£70m about 0.71. The lower the value, the cheaper the company. A value below one suggests you can buy it for less than it is actually worth.

Does it work?

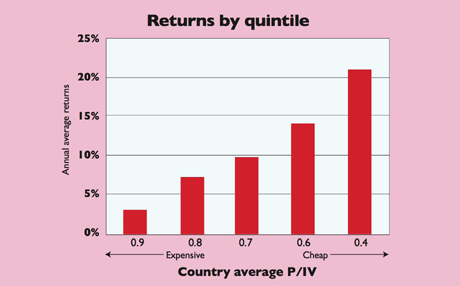

Thomson Reuters looked at this at a country index level, to see which markets were cheapest. Its research suggests that picking the cheapest countries on the p/IV measure would have made you annual returns of more than 21% over the last 15 years. Buying the most expensive countries using the ratio would have returned just 3% on average over the same period. What's more, these countries only outperformed their cheaper peers in one of the 15 years.

Very cheap countries also demonstrated mean reversion'. This is the tendency of extreme results to return to normal' over time. In other words, unusually cheap markets get more expensive, and unusually expensive ones get cheaper. Markets in the cheapest fifth (quintile) of the research rose from having an average p/IV of 0.4, to an average of 0.6 five years later, meaning that, over time, their share prices gradually rose closer to their intrinsic value.

What to buy

So which countries look cheap now? The cheapest five using the p/IV method are Bulgaria (0.28), Russia (0.36), Pakistan (0.41), Egypt (0.42) and Hong Kong (0.51). These aren't the easiest countries to invest in, and you might argue that some are cheap for a reason. We'd leave Pakistan, Bulgaria and Egypt to one side.

For the other two, the most liquid is probably Hong Kong, which you can buy via the iShares Hong Kong exchange-traded fund (US: EWH). If you can bear the political risk, buy Russia via the iShares Russia capped ETF (US: ERUS).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?