Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

I know I'm supposed to be taking the summer off, but comments on Twitter from Alan Beattie, international economy editor of the Financial Times, raised hackles and lured me from my bunker.

Beattie declares that there is "no fundamental valuation model" for gold; that "it pays no interest" and that therefore it's "intrinsically speculative". Really?

These are common arguments we hear from the gold-has-no-use brigade. I want to address them.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

First, gold pays no interest. True. But then, nor does cash - unless you lend it to people. The world needs to realise that by putting cash in the bank you are lending it. Gold can pay interest - if you lend it out. And lots of people do (though for what purpose I cannot say).

But in this environment of negative real rates (when the central bank rate of interest is below the rate of inflation), who gives a hoot about interest anyway? 1 or 2% interest. Whoopee-do.

Next, there's this idea that "gold has no use". Really?

Gold has very little industrial application, yes. It's too expensive. But no use?

Gold, unlike bubbles and government bonds, lasts forever. This makes it a highly effective form of money, as I'm about to explain.

But how can gold be money, runs the next argument, when you can't go into a shop and buy stuff with it? Absolutely. You can't.

Err ... actually, you can. The gold sovereign is still legal tender. But it only has a face value of one pound, when it's worth over £250. You'd be a plum if demanded that some poor shopkeeper accept it as payment. (And he'd be a plum if he refused it). But I'm splitting hairs.

As a day-to-day medium of exchange, gold has never found much use. A piece of gold the size of a penny (about £125 or $200 in today's money) contains too much value for anything other than expensive transactions. Copper, nickel, silver, paper and now digital money have all found far more prolific use.

But to assert that you can't buy stuff with it therefore it isn't money, is a facile and ignorant argument. Money is more than just a medium of exchange. Indeed, this is just one of the three essential functions of money: it also has to act as a store of wealth and as a unit of account.

It is gold's very inert, intrinsic, eternal uselessness - and we have Mother Nature to thank for that - that makes it such an effective form of money. It has no other function other than to be a store of wealth. Even its use in jewellery is an extension of that function - to store (and display) wealth.

Governments can't print gold, they can't 'quantitatively ease' it, they can't loan it into existence. They can't debase it the way they do their own currencies. It just stays there, unconsumed, forever. Which all means that gold is constant - and therefore an excellent unit of account, far better than government money.

Demand for a store of wealth tends to fall during times of economic expansion - such as in the 80s and 90s - and so the gold price falls. People are looking for opportunities to grow their wealth, not simply hang on to it.

On the other hand, demand for gold increases during periods of economic contraction and monetary stress - such as we have experienced, on and off, since the turn of the century. These are times when people are more concerned as the oft-quoted saying goes - about the return of their capital, rather than the return on their capital.

Gold's fundamental use is to be money.

But how do you value gold?

Let's move on to some fundamental valuation models.

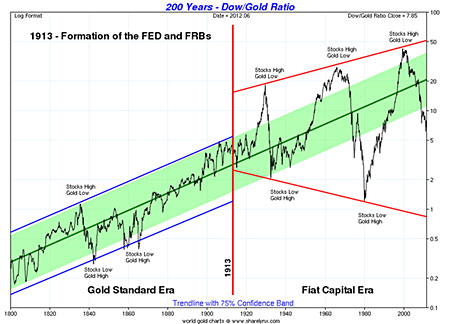

Ratios are the simplest. There all sorts for gold. You look at the ratio of gold to any asset - stock markets, house prices, food, currencies, bonds or commodities - over a time frame that suits your investment horizon and you quickly get an idea of value and trend.

Here, by way of an example, I show the historical ratio of the price of gold to the leading American public companies - the Dow. This chart (my thanks to Nick Laird of sharelynx.com) is on a 200-year timeframe. But you can look at the ratio on an intraday basis too, if you so desire.

(Click on the chart for a larger version)

Next, I want to suggest another, rather more hardcore valuation model.

In the global rushes for liquidity of 2008 and now, the government bond markets of the US, UK and Germany have been investors' safe havens of choice - not, to the surprise of many, gold. But how long can this go on for?

The implosion of the government bond market is every goldbug's dream. That's when gold resumes its safe haven role as money of last resort. There are all sorts of things that could trigger said implosion. It may or may not happen. But the more they print, the more they debase, the more likely it becomes.

In such circumstances, you might consider as your fundamental valuation model, the ratio of the senior economy's gold holdings (261 million ounces, in the case of the US, though this is unaudited) to its external debt (now about $5 trillion). To pay off its external debt with its gold, the gold price would have to be some $19,000 an ounce.

LOL.

Or you could look at the Federal Reserve Monetary Base (money on issue), which now stands at $2.6 trillion. For this to be 100% backed by gold, you're looking at $10,000 per ounce.

LOL again.

As a point of note, during the 19th century, the pound was usually only about 25% backed by gold. In periods of stress this went to 50%. In booms it went to 15%. (I outlined this previously here). If the dollar today's global reserve currency was to be 25% backed, the model would give a price of $2,500 per ounce.

But if gold went to 25% of the MZM (money with zero maturity) money supply measure, the price would be higher. I quote Tom Fischer, professor of mathematics at the University Of Wuerzburg, who has devised this model.

"The rationale of the model is fairly simple. MZM, ie financial assets redeemable at par on demand, is what the Federal Reserve system has to underwrite in the case of a banking crisis to avoid panics. If the central bank fails to underwrite sufficiently large parts (potentially all) of MZM, a panic might ensue where money could be withdrawn in such large amounts that it could become systemically dangerous. The Fed therefore has no choice: it has to underwrite MZM."

Current MZM stands at just under $11 trillion. Divide that by the 261 million ounces of US gold and you arrive at a figure of $42,000 per ounce. 25% of that is $10,500.

What's interesting about this figure is that, at the now-infamous 1980 gold spike to $850 an ounce, US gold holdings did go to 25% of MZM, so that's another possible model.

The notion of gold officially resuming its natural and historical role as money is one that has steadily been gaining traction since the turn of the century. Unofficially it already has - hence this bull market. But all of the above models rely on that notion gaining broader public and market recognition, plus some kind of official recognition - be it in the form of some kind of gold standard or confiscation.

The resumption of this role may never happen and gold could some become obsolete commodity. I wouldn't bank on it though. In fact, given the way this banking crisis is unfolding, I'd bank on the opposite. Just expect wild, wild volatility en route.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your bill

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your billHundreds of thousands of pensioners will be dragged into paying income tax due to an ongoing freeze to tax bands, forecasts suggest

-

Stock market circuit breaker: Why did Korean shares pause trading?

Stock market circuit breaker: Why did Korean shares pause trading?The fallout from the conflict in the Middle East hit the Korean stock market on 4 March, with shares forced to temporarily stop trading. What is a stock market circuit breaker, and why did the KOSPI trigger one?