How to measure the value of your investment decisions

In calculating the 'economic value added' (EVA) of your investment decisions, you can identify those companies which create value from those which destroy it. Tim Bennett reveals what EVA is, how well it works - and where to find the companies that offer the best EVA.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

It's easy to forget that every investment decision comes at a price the other ways in which you could have used your money. For example, if you choose to buy shares, then you are sacrificing the chance to put the same money to work in a bank account, a government bond, corporate bond or even at the racetrack.

The fact that few investors pay attention to this 'opportunity cost' allows many company directors to get away with murder. They proudly cite the returns from projects or acquisitions that a firm has undertaken, with no mention of what those cost in terms of the debt and equity capital committed.

The measure 'economic value added' (EVA) tries to correct this. As Jen-Ai Chua and Amar Gill of broker CLSA put it, "companies create positive economic value only if they generate returns on capital in excess of cost of capital". Such firms are "value creators". Companies for whom the reverse is true are "value destroyers". So how is EVAmeasured?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What is EVA?

The best firms are those where the 'return on invested capital' (ROIC), say 10%, exceeds the weighted average cost of its capital (WACC see below), say 5%.

To calculate ROIC, take net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) and divide it by a firm's tangible capital employed (so intangibles such as goodwill are taken out). The bigger the gap, or 'spread', between ROIC and WACC in this case 5% the better. That's fine, but a percentage tells you nothing about scale.

If I borrow £1 at an interest rate of 1% and invest it to earn 20%, ROIC, ignoring tax, exceeds my WACC by a solid 19%. But unless I can repeat the same trick for a much larger sum, it'll be a long time before I am rich.

So another way to measure EVA is to take a firm's NOPAT, say £100m, and deduct a charge to reflect the cost of capital (say £60m) to give an absolute number in this case £40m. Big is better. A small, or negative, figure is bad news.

Another problem with EVA is you need to do some number crunching you won't find the numbers you need in the published accounts. But CLSA reckons it's well worth the effort.

How well does EVA work?

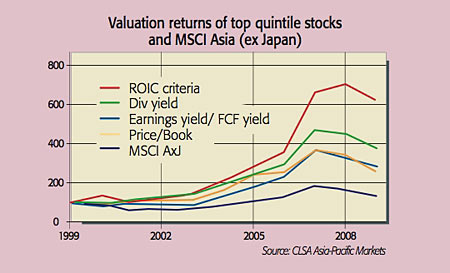

CLSA has tested investment strategies based on buying the top stocks in terms of ROIC, against the results achieved using various other common valuation measures over the last ten years (see the chart). These include the dividend yield, price/book ratio, earnings yield (the p/e ratio flipped on its head), and free cash flow yield (annual cash flow after deducting non-discretionary payments, divided by the share price). The benchmark used was the MSCI Asia ex-Japan index, which managed a compound return of just 2.8%.

The result? Well, as CLSA notes, high ROIC companies, especially when backed by a high EBIT/EV ratio (operating profit divided by the market value of debt and equity), had "the strongest returns of our valuation screens and were also the most consistent outperformers". Indeed, high ROIC firms managed a compound return of around 20% over the past ten years.

So, what to buy?

Despite a heady rise for Asian stockmarkets this year, the gap between ROIC and WACC is still highest in China (6%) and India (also 6%). Indonesia also does well on 5%. Markets to avoid, where EVA is close to zero, or negative, include Hong Kong, Korea and Malaysia. In sector terms, CLSA likes technology- or energy-related stocks. These offer average EVA spreads of 5% or more. Property and transport, on the other hand, are largely duds. Try Australian telecoms firm Telstra (ASX: TLS), Taiwan's Chungwa Telecoms (NYSE: CHT) and China Mobile (HK: 0941).

How to calculate cost of capital

Most firms have two types of capital debt and equity. The cost of debt is fairly simple the interest rate multiplied by (1 minus the firms' corporation tax rate). This adjustment reflects the fact that interest payments are tax deductible. So if the interest rate is 8% and the firm's tax rate 30%, the cost of debt is 5.6% (8% x 0.7). Next, cost of equity. Here analysts start with the risk-free rate available on a five or ten-year government bond on the basis that this is the minimum return an investor should demand. This is then adjusted higher by an equity risk premium. This is the extra return that a shareholder should want given that a firm may not pay a dividend, or could go bust. So, if the risk free rate is 5%, and the equity risk premium 6%, the cost of equity is 11%.

Finally, if a firm is 60% equity funded and 40% debt funded, the weighted average cost of capital is (0.6 x 11%) + (0.4 x 5.6%), which equals 8.84%. If the firm's management can't generate a ROIC that beats this hurdle rate, the firm is a "value destroyer".

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.