Goodwin: A superlative British manufacturer to buy now

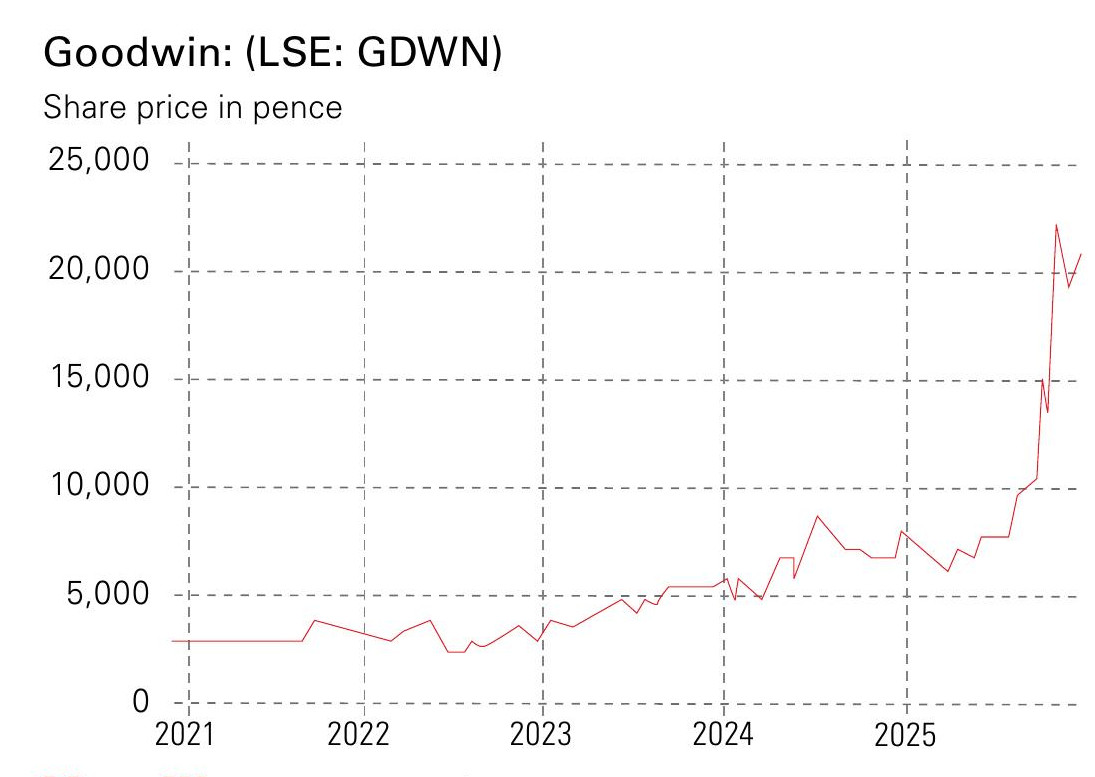

Veteran engineering group Goodwin has created a new profit engine. But following its tremendous run, can investors still afford the shares?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

If you want proof that British manufacturing isn’t dead, take a trip to an unassuming stretch of Stoke-on-Trent. There, on the same site it has occupied since Victorian times, sits Goodwin (LSE: GDWN), a heavy engineering group that has become one of the most profitable specialist manufacturers in the country.

It may not be glamorous, but Goodwin produces the components that keep critical national infrastructure running, such as precision-cast nuclear-waste containers for Sellafield, high-integrity parts for naval propulsion systems and specialised valves for the liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry. These are the bits that no one can afford to get wrong; and its excellence in these areas is why Goodwin is so profitable. But following its tremendous run, can investors still afford the shares?

Goodwin is keeping it in the family

Goodwin was founded in 1883 by Ralph Goodwin and, unlike most of its peers, has remained firmly under family control ever since. The modern business is still chaired by a Goodwin, still run by Goodwins, and still majority-owned by the Goodwin family.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Normally that might raise questions about governance. In Goodwin’s case, it has been its greatest strength. Family ownership has allowed the group to invest patiently over decades, avoiding the usual temptation to juice short-term profits. Instead, it has focused on landing long-horizon contracts where quality and reliability matter more than price. This persistence explains why the business is so well respected in industry. Its decades of excellence give it the kind of reputation that is almost impossible for a newcomer to replicate.

One thing that sets the business apart is a bold strategy to embrace change rather than be hostage to it. Ten years ago, Goodwin looked tied to the oil and gas market. When oil prices collapsed, the company faced a choice: to shrink with the market or reinvent itself. It opted for reinvention. The group pushed aggressively into sectors with high barriers to entry, such as defence, nuclear power and other specialist markets where components require complex metallurgy and spotless quality records.

More striking is what comes next. Management, usually conservative to a fault, now expects pre-tax profits to double to more than £71 million this financial year. The firm has a record £365 million order book to back up that forecast, stretching over many years thanks to nuclear-decommissioning projects and the UK’s next generation of nuclear-powered submarines.

Goodwin’s financial discipline is unusual

Unlike many industrial companies, Goodwin is not a cyclical business that generates modest but unspectacular returns. It has become a high-margin supplier of mission-critical parts to programmes that governments and businesses cannot cancel.

Goodwin’s financial discipline is unusual. Instead of loading up on debt to fund new capacity, it uses what it calls a customer-funded investment model. In practice, this means major capital expenditure is tied directly to long-term customer contracts. The customer commits; Goodwin invests. It’s incredibly conservative and effective. Cash generation has surged. Net debt has collapsed and is heading for zero. The board has responded with a 111% increase to the ordinary dividend, plus a large special dividend for good measure.

In a market where many engineering groups rely on hefty borrowings or dilutive equity raisings to grow, Goodwin stands out. It’s expanding while also deleveraging. Most investors will be focused on that. Yet Goodwin has a second act that could be worth more than the whole group in time. That business is Duvelco, its advanced-materials subsidiary, built around a patented polyimide called Ducoya. This has chemical characteristics that make it ideal in industries such as aerospace, which supports exceptionally high margins as its customers place a premium on proven performance. Supplying these markets requires technical qualification and rigorous testing. This long, complex accreditation process creates exactly the sort of barrier to entry that Goodwin has historically excelled at building.

Goodwin has broken its rule by funding the new pressing facility entirely from its own cash. That’s unusual for a group that normally relies on customer-backed spending. Management clearly believes Ducoya could become a profit engine in its own right. Yet, for all the optimism, the forecasted doubling of profits to £71 million doesn’t include contribution from the subsidiary.

Goodwin is worth the premium

Goodwin’s promotion into the FTSE 250 has put it firmly on the radar of index trackers and mainstream funds. The shares have re-rated sharply and now trade at a clear premium to traditional industrial peers.

Is that a problem? Possibly. This is still a specialist engineering company with limited free float, large exposure to big government projects and a management team that communicates sparingly. Those factors can make the shares volatile. Yet few listed UK manufacturers can point to a multi-decade record of quality with a pipeline of government-backed projects. On top of that, it has a near debt-free balance sheet, rising margins and an exciting advanced-materials subsidiary. The premium multiple reflects this reality.

The shares aren’t cheap, but neither is what you’re buying. For patient investors willing both to tolerate limited liquidity and trust in the family’s long-term stewardship, Goodwin remains one of the few genuinely high-quality industrial compounders left on the London market. If you’re already on board, it’s a strong hold. If you’re not, it’s one to buy on any meaningful pullback.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jamie is an analyst and former fund manager. He writes about companies for MoneyWeek and consults on investments to professional investors.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

Three Indian stocks poised to profit

Three Indian stocks poised to profitIndian stocks are making waves. Here, professional investor Gaurav Narain of the India Capital Growth Fund highlights three of his favourites

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

The scourge of youth unemployment in Britain

The scourge of youth unemployment in BritainYouth unemployment in Britain is the worst it’s been for more than a decade. Something dramatic seems to have changed in the labour markets. What is it?