The Federal Reserve has turned inflation-fighter – how do you invest now?

The US Federal Reserve has become much more hawkish on inflation and less concerned with the markets' reaction to rising interest rates. John Stepek explains way, and picks the best sector to buy to take advantage.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Ever since the late 1980s or so, the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, has earned itself a justified reputation for being a pushover when it comes to markets.

This manifested itself in the phrase the “Greenspan put”. This was the idea that Alan Greenspan, Fed governor between 1987 and 2006, would always act to cushion markets if they looked wobbly.

The “put” survived Greenspan. His successors, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, always managed to be more “dovish” than markets had expected.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

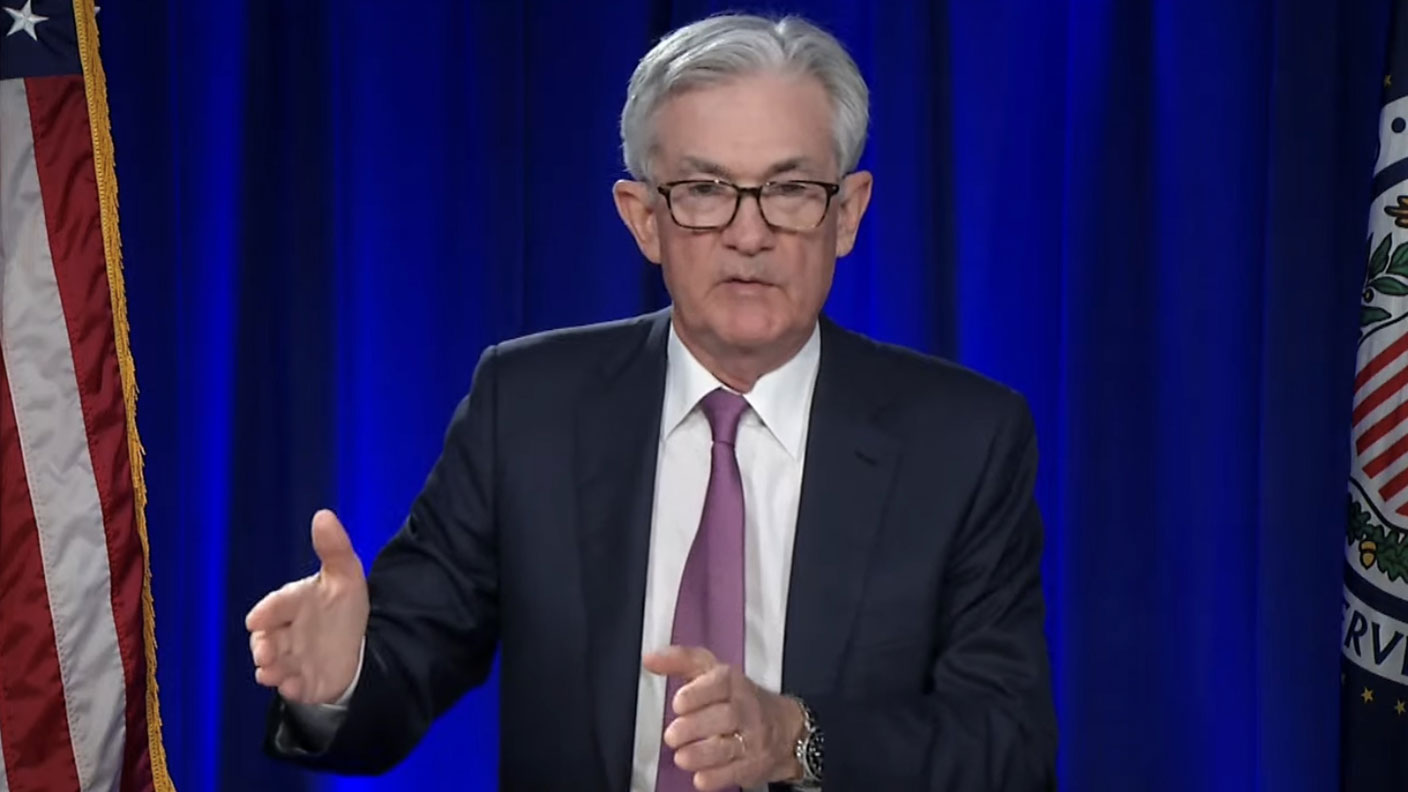

Last night, current Fed chair Jerome Powell bucked the trend. And investors didn’t like it one bit.

Why the Federal Reserve has changed course

The Federal Reserve had its first interest-rate setting meeting of the year this week. Last night (UK time) they told us what they’d decided.

The actual decision wasn’t a surprise to markets, but the tone – showing no signs of concern about the recent market sell-off, for starters – was a lot more hawkish than investors had expected.

As a result, markets now expect interest rates to rise further and faster than they did before.

So what did the Fed say? Come March, the Fed will stop printing money to buy assets (ie quantitative easing – QE – ends). Not only that, but it’ll probably raise interest rates – maybe even by half a percentage point, not just a quarter point. Not only that, but it’ll quite likely start quantitative tightening (QT) at some point soon after that.

QT involves the Fed reversing QE. In other words, it doesn’t just stop printing money to buy assets, it starts to sell off the assets that it has already bought.

The real shift was in Jerome Powell’s tone. Markets quite often expect to get a bit of coddling from the central bank boss, particularly if rates are going up.

Not a bit of it this time. Powell emphasised that he’s worried about inflation. He emphasised that he sees inflation as a risk to workers and the labour market (usually, the labour market has been seen as a reason to keep rates low).

Most importantly, as John Authers points out on Bloomberg, “the central bank has also shown that it can live with the amount of equity market turbulence that it’s created so far”. There may well be a “Powell put”, but if there is one, it kicks in at a much lower price than investors have grown used to in the Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen years.

What’s behind the change of strategy? As we’ve noted before, this is all driven by inflation. Powell’s predecessors had it easy. When you’re more worried about deflation than inflation, you can just print more money. That makes you popular.

Inflation is much harder to tackle. It’s now a headline issue, which means it’s a political issue (both here and in the US), which means that suddenly it’s public enemy number one, which means that Wall Street needs to fend for itself.

From that point of view, it’s better for Powell to talk tough now and get the market to tighten financial conditions for him (a stronger dollar and a weaker stockmarket are both forms of tightening), rather than leave it until he needs to do something much more drastic.

In effect, he’s hoping that a stitch today will save nine later. Because if inflation doesn’t go away, the level that interest rates might have to rise to would be very damaging indeed. So I wouldn’t expect Powell to shift course until there are either signs of serious financial distress (in credit markets say) or signs that inflation is alleviating (though I think he’d want to see more than just one or two readings before he changed tone).

What does this mean for your money? Buy banks, for one

We’ll keep an eye on all that. But meanwhile, what does this hawkishness all mean for your portfolio?

It’s easy to get caught up in the idea that a sliding US stockmarket will drive everything down with it. That’s a reasonable assumption, because it very often does.

However, the good news (for UK investors in particular) is that there are some industries that like rising interest rates. Bank stocks finally seem to be waking up from a lengthy slumber.

For example, Lloyds (which I own) is up around 5% so far this year. For perspective, the FTSE 100 – which of course also benefits from big oil, as well as the banks – is just about flat, and the Nasdaq composite is down nearly 15%. And Lloyds is far from being the only one.

It’s striking that the tech bubble and bust of the late 1990s saw the big tech companies falling out of favour and being neglected by investors for a good decade or more. After the fallout from that bubble, during the 2000s, the places to be were commodities and – in some cases – the financial sector.

Since the global financial crisis, banks outside the US have been largely neglected or treated as pariahs, certainly the boring old UK ones, which were detested by consumers (in many cases, rightly) and also subject to one of the biggest backdoor “QE for the people” schemes in history, the PPI scandal.

It’ll be fitting if the bursting of the current tech bubble (because arguably that’s what it is) coincides with a new bull market in neglected financials and other “dinosaur” stocks.

In fact, Julian Brigden of Macro Intelligence 2 Partners puts it very well in the latest MoneyWeek podcast, when he tells Merryn: “the first shall be last and the last shall be first”. You should definitely listen to this one if you haven’t yet – just click here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?With gold and silver prices having outperformed the stock markets last year, mining stocks can be an effective, if volatile, means of gaining exposure

-

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealth

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealthPeople squeezed between caring for ageing parents and adult children or younger grandchildren – known as the ‘sandwich generation’ – are at risk of neglecting their own financial planning. Here’s how to protect yourself and your loved ones’ wealth.

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'Opinion Say goodbye to the era of central bank orthodoxy and hello to the new era of central bank dependency, says Jeremy McKeown

-

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?It seems clear that Trump would like to sack Jerome Powell if he could only find a constitutional cause. Why, and what would it mean for financial markets?

-

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?Donald Trump has been vocal in his criticism of Jerome "Jay" Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve. What do his threats to fire him mean for markets and investors?

-

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?Analysis Free banking is one alternative to central banks, but would switching to a radical new system be worth the risk?

-

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?The risk of an escalating Middle East crisis continues to rise. Markets appear to be dismissing the prospect. Here's how investors can protect themselves.