Markets slump as the central bank liquidity flood recedes

As central-bank largesse comes to an end, stocks are starting to look very highly valued indeed. Marina Gerner reports.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

"My, my", says David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff. "The president hasn't tweeted about his effect on the stockmarket since 3 October." Like all investors, he's had a nasty fright. The past few weeks have not been "as cataclysmic" as October 2008, 1987 or 1929, says Randall W Forsyth in Barron's. "But bad enough."

By mid-week, America's S&P 500 index had slipped by more than 8% in October and was heading for its worst month since February 2009. In just five weeks the index has fallen by more than 10% from a record peak, and this week it entered negative territory for the year. A decline of that magnitude defines a correction, a 20% slide means a bear market. The Nasdaq Composite index slumped by 4.4% last Wednesday alone, its worst day in seven years.

US stocks rejoin global trend

Stocks outside the US have been struggling for some time. A FTSE index covering global stocks but stripping out the US has fallen by 14% this year. The latest bout of selling on Wall Street undermined confidence elsewhere, too. The pan-European Stoxx 600 is at a two-year low. The MSCI Asia ex-Japan index has fallen 23% since January, dragged down by China's bear market (see box, right). The FTSE 100 has lost all the gains it made this century.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Storm clouds gathering

Several immediate worries, along with a major structural shift, explain the frenzied selling. The trade war between America and China is beginning to hamper the performance of US industrial blue chips Caterpillar and 3M warned that tariffs on Chinese imports were raising their costs. Meanwhile, many fund managers see the German economy "as a proxy for world trade", notes Ian King on Sky News. So investors concerned about the world trade outlook "will sell the German market above all others". This helps explain the DAX index's 18% decline this year.

We have hit peak earnings

Investors have also "latched on to the narrative that US corporate earnings have peaked and that the tailwind" from the Trump administration's tax cuts will fade, says Michael Mackenzie in the Financial Times. Over the past decade the bull market in the US has been powered by the FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google). Amazon last week delivered record profits of almost $3bn for the past three months, but revenue growth was slower than expected.

Google's parent company Alphabet also missed analysts' revenue expectations. This has prompted an exodus from tech, with the FANG stocks losing 14% this month. Amazon has shed a quarter of its value from a record high in early September.

"We're going through this transition where, earlier in the year, the corporate earnings results were just a blowout and now they're more mixed," David Lefkowitz, senior equity strategist for the Americas at UBS Global Wealth Management, told The Guardian.A stronger dollar (half the S&P 500's sales are made abroad) and a slower global economy will also cause a shift from a period of double-digit, year-on-year earnings-per-share growth to a far slower pace. Investors are also cottoning on to a new obstacle for margins and profits.

Workers strike back

US unemployment is at a record low and wages are on the rise. In August they grew by 2.9% year on year, the fastest pace since the crisis. The tight labour market and eye-catching pay increases for low-paid workers at Amazon suggest the trend will endure, as does survey evidence. In early summer a record percentage of US small businesses said they couldn't find the right people to fill their open positions. Staff costs will henceforth increasingly erode margins. The same applies to potential new global taxes on multinationals. Signs of incipient inflation, meanwhile, have fuelled worries over higher interest rates curbing growth.

"Put bluntly," says Mackenzie, "this means valuations are unsustainable." The US market recently reached a structurally adjusted price-earnings ratio of 32 a figure only exceeded during the tech bubble madness in the late 1990s. With earnings growth heading in the wrong direction, stocks shouldn't be priced for perfection.

Another euro headache

A further concern is that "the eurozone crisis, it seems, isn't dead, but was only resting", says Jeremy Warner in The Sunday Telegraph. The new populist government in Italy has "deliberately embarked" on a budget that will break the eurozone's fiscal rules. Fears of another standoff with Brussels help explain why the Italian economy stagnated in the third quarter. The year-on-year eurozone growth rate has dropped to 1.7%.

The money flood recedes...

The underlying problem, however, is that all these issues are coming together just as the rising tide that has lifted all boats over the past decade is receding. The days of easy money are over. The US, having ended its quantitative easing (QE) policy, whereby it injected money into the economy by buying bonds with printed cash, is now doing the opposite.

Quantitative tightening (QT) means it is withdrawing money from the system by selling the bonds to the tune of $50bn a month. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank (ECB)has been tapering its QE. Bond purchases fell from €60bn a month in 2017, to €30bn in January. ECB president Mario Draghi plans to end QE by the end of the year. The Bank of Japan has also taken its foot off the accelerator.

...so markets will lack support

Central banks spent vast sums propping up the system. Japan's has ended up with assets worth around 95% of GDP on its balance sheet, while the US Federal Reserve's was worth around a quarter of GDP at the peak of QE. Printed money has to go somewhere, and much of it went into asset markets. "The central bank liquidity torrent has penetrated every nook and cranny of markets, from fine wine and art to real-estate, junk-rated bonds and emerging markets," say Sujata Rao and Dhara Ranasinghe on Reuters.

And now markets will have to cope without easy money. Central bank money will dip to around zero by the end of this year and go negative in 2019 they will be taking money out of the system for the first time in nearly a decade. Meanwhile, the era of zero-interest rates, which have stimulated lending and liquidity, is over, too. The Fed has raised the price of money eight times since 2015; the benchmark rate is now at 2%-2.25%.

Many central banks in emerging economies have been raising rates, too. While a new "normal" monetary policy backdrop might seem long overdue, the problem is that the world economy looks very vulnerable to dearer money. Ten years after a crisis caused by too much debt, we have even more. The International Monetary Fund calculates that global borrowings (public and private) are worth 225% of GDP, up by 12% in the past ten years.

Slow strangulation

Gauging the impact of monetary tightening is hardly an exact science, but it looks a daunting prospect. One German newsletter estimates the Fed will have removed $900bn from the system by the end of next year. Along with the rise in the dollar earlier this year and the Fed's interest-rate rises to date, this tightening represents a US rate hike of 5%, it reckons. So it looks as though global markets face "slow strangulation", as Pictet Asset Management's Steve Donz puts it.

Whatever the ultimate impact on the debt-soaked global economy, the key point for markets is that the turning of the liquidity tide has created a more difficult backdrop. "We need to go through a period of adjusting in sentiment and valuation terms to a more mixed reality where you don't get both economic recovery and cheap money," as Sunil Krishnan of Aviva Investors told Reuters.

This implies the sort of market movements we saw last week. Investors are starting to take a far less forgiving view of highly-valued tech stocks. They are also paying closer attention to geopolitical problems that until recently could be alleviated, if not resolved, by central bank action witness the ECB's QE keeping Italy's borrowing costs artificially low.Now that the high of easy money is wearing off, investors should be more circumspect and focus more on the fundamentals. The atmosphere will be more reminiscent of the pre-money-flood days.

Correction or rout?

The end of easy money is hardly a secret, but as so often in markets, the "Wile E Coyote syndrome" plays a part, as Jeremy Warner points out in The Sunday Telegraph. Like the cartoon character, investors keep running after leaving the edge of a cliff. It now seems that US investors, who had kept buying while doubts were creeping in elsewhere, have looked down and started to adjust to the prospect of dearer money.

Still, while further stockmarket gains look a tall order, "there is no reason, for now, why the correction should become a rout", as the FT points out. The US is still growing at an annualised rate of 3.5%, and the International Monetary Fund is pencilling in a similar growth rate for the world economy in 2018. About 85% of global fund managers believe the world is in the "late cycle" period of growth, according to the latest Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey.

For now, as we noted earlier this month, investors should shift to a more defensive stance, rotating from growth to value and making sure their gold holdings are topped up. Markets will struggle to adjust to the new (old) normal, but it's too soon to flee the scene.

China: the centre of the global storm

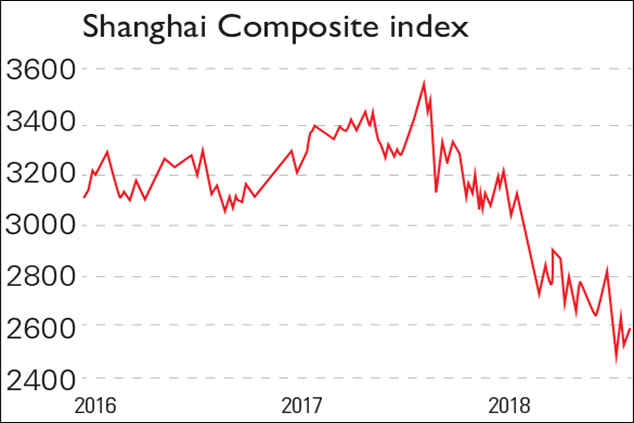

This year's 27% slump has brought the Shanghai Composite Index down to 2008 levels, making it one of the worst-performing markets of the year. Chinese stocks dominate emerging-market indices, undermining sentiment elsewhere.

The economy has been slowing since 2014, says the Financial Times, as authorities hope to "engineer a soft economic landing" after a "long construction-driven, debt-fuelled growth spurt". A key element of this plan is to clean up the opaque shadow banking system (non-bank sources of credit). The longer-term aim is to shift from exports and investment to a services- and consumer-orientated economy without damaging growth excessively.

Progress looks slow, says Standard Chartered, pointing to "increasing cases of debt defaults, failed land auctions and bailouts of listed companies", which appear to be "symptoms of... deep-rooted problems." This tightrope-walking has become much harder now that rising US interest rates and a stronger dollar are drawing money away from emerging markets. And then there's the trade war with the US. Hopes that the Trump administration "will strike a speedy" deal with Beijing are fading, says The Economist.

Investors have been reminded that "China's problems can quickly become the world's problems", as Reshma Kapadia notes in Barron's. It's the world's top exporter and third-largest importer, integral to manufacturing supply chains. It's also the biggest consumer of cars, copper, and iron ore. China's share of global GDP has risen from 5% in 2005 to 15% last year, according to Capital Economics.

The US-China trade war is already disrupting the electronics supply chain in Asia. Around 30% of China's exports last year contained other countries' inputs and components, says Aidan Yao in the South China Morning Post. Japan, Korea and Taiwan look most vulnerable in this context. However, there has been greater foreign direct investment into Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, "as firms adopt a more flexible production network outside China to circumvent the tariffs".

The worst of China's bear market may be over, says Randall W Forsyth in Barron's. The government has promised "unwavering support" for the private sector, so various stimuli now look likely. This could store up trouble for later by adding to the debt pile, but it may also mean that investors in China can look forward to recovery just as global markets top out.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Marina Gerner is an award-winning journalist and columnist who has written for the Financial Times, the Times Literary Supplement, the Economist, The Guardian and Standpoint magazine in the UK; the New York Observer in the US; and die Bild and Frankfurter Rundschau in Germany.

Marina is also an adjunct professor at the NYU Stern School of Business at their London campus, and has a PhD from the London School of Economics.

Her first book, The Vagina Business, deals with the potential of “femtech” to transform women’s lives, and will be published by Icon Books in September 2024.

Marina is trilingual and lives in London.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge