Interest rates are rising – time to change strategy

The recent wobble in markets was largely down to one thing – rising interest rates. John Stepek looks at what it means for your portfolio.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The recent wobble in markets was largely down to one thing the days of easy money are at an end. John Stepek looks at what it means for your portfolio.

"I think the Fed has gone crazy." That was US president Donald Trump passing judgement on what spooked markets last week. On Wednesday the Dow Jones index dropped by 3.2%, its biggest such fall since February's spasm of panic. Trump's ire raised many an eyebrow. US politicians are supposed to respect the Federal Reserve's independence, although in reality most presidents in the past have grown at least a little edgy when the Fed has started hiking rates rather than cutting. But whatever you think of Trump, he is broadly correct on the root cause of the correction. There are many reasons for markets to be jittery I've highlighted two key concerns in the boxes below but the primary driver of the most recent sell-off has been a wave of fear about rising interest rates.

As the chart below shows, the yield on ten-year US Treasuries (what it costs the US government to borrow for a ten-year period) has spiked above 3.25%, and is close to its highest level in seven years. Rates are rising because the US economy is strong growth is solid, with unemployment at multi-decade lows. That suggests rates should be higher to prevent inflation still quiescent, but showing signs of stirring from taking off. Markets now believe that the Fed will raise interest rates once more this year, and then again three times in 2019. As Bob Prince of hedge fund giant Bridgewater Associates sums it up in the Financial Times: "We are clearly shifting from an era of monetary easing to monetary tightening."

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In theory, that's good news. After all, wouldn't we all like to get back to "normal" after the fallout from 2008? The problem is, we've grown rather too used to low and falling interest rates. Bond yields have been falling since the early 1980s, and since 2008 we've had a long period of near-zero interest rates and money printing (quantitative easing, or QE). With debt that cheap, households, governments and companies have all borrowed freely, with the result that global debt levels have risen, not fallen, since the financial crisis. As that debt pile starts to become more expensive, the consequences will make life a lot harder for investors.

The corporate-debt bubble

One of the most obvious concerns for investors comes from corporate indebtedness. In the past decade, the quantity of outstanding US investment-grade corporate debt has grown from $1.8trn to more than $5trn. Not only is there a lot more corporate debt, but its quality has fallen too. In 2008, companies with a credit rating just one notch above "junk" or "high-yield" status accounted for about a third of the issuance of investment-grade debt. Now it's nearly half, notes the FT. That could result in a spike in borrowing costs for any companies that turn into "fallen angels" formerly investment-grade firms that have been downgraded to junk territory.

And while this isn't welcome news for corporate bond investors (the price of such bonds tends to fall as both interest rates and investors' concerns about credit quality rise), it's bad news for stockmarkets too. Equity investors tend to forget during the good times that they are behind debt holders in the queue to get paid. That matters because companies have increasingly swapped equity for debt at low interest rates effectively remortgaging themselves which has made their balance sheets riskier.

Yet equity investors have been happy to ignore this because much of this debt has been used to fund buybacks or dividend payouts. That will become impossible as rates rise, notes Lu Yu of M&G Investments on the Bond Vigilantes blog. "Highly-indebted companies are most at risk and investors should therefore expect less generous dividend policies as well as fewer share buybacks going ahead." As a result, "investors may start paying more attention to free cash flows from now on, as higher rates start eating into one of the most truthful measures of corporate performance".

What's next for the economy?

In the longer run, there is also the question of what higher rates mean for the broader economy. So far, rising rates have driven up the US dollar, which in turn has been particularly painful for countries with debt denominated in dollars, or those that depend on a steady stream of capital inflows from investors. Indeed, global markets have already had a very tough 2018 until now, the US has been an outlier. The FTSE World index, excluding the US, has already fallen by about 16% from its January high. Higher rates also spell bad news for overpriced property markets if the cost of credit goes up, prices have to fall. Luxury property in "global" cities, which is also being hit by high-end capital controls, looks particularly vulnerable. In the longer run, there's the question of how governments can afford the interest bills on their own huge debt piles in the absence of QE.

For now, this is a slow-burning process. Bond yields have crept higher in a stop-start manner, and until there is unequivocal evidence of wage inflation taking off in the US that could remain the case. Also, global fund managers are bearish right now, according to the latest Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey, which is typically a good contrarian signal as if to prove them wrong, the market rebounded strongly on Tuesday as results from the likes of streaming service Netflix and financial services giant JP Morgan beat hopes. So we may not be facing the "big one" yet. However, it's a good idea to move your portfolio towards being more defensive if you haven't already done so.

What to do now

Tech stocks have been among those hit hardest by fear of rising interest rates. This makes sense. When rates are low, and growth is scarce, investors will pay a premium for companies that promise rapid and ongoing growth in the future. As rates start to rise, investors grow more interested in getting paid today. That makes the tech sector and other growth stocks very sensitive to changes in rates. I am reluctant to suggest you sell out of MoneyWeek's favourite growth fund Scottish Mortgage Trust (LSE: SMT), which has fallen hard in recent weeks as timing these shifts is impossible. But if you haven't rebalanced your portfolio recently, it might be worth moving some profits into "value" investments, and funds more orientated towards bear market conditions, such as Personal Assets Trust (LSE: PNL)

Banks have been in the doldrums for a long time, and should benefit from rising interest rates (which should make them more profitable), but you need to be picky. European banks look cheap but they're exposed to risks (see the box on Italy). One value-oriented investment trust with heavy exposure to UK-listed banks is Temple Bar (LSE: TMPL). It's also worth making sure you own some gold, which tends to do well when inflation is rising and fear for the financial system's integrity is rising. Both look likely in coming months and years. You can buy directly or via an exchange-traded fund such as ETFS Physical Gold (LSE: PHAU). Gold mining stocks have also fallen hard over the past year or so now might be the time to top up. VanEck Vectors Gold Miners ETF (LSE: GDX) tracks the NYSE Arca Gold Miners index.

Italy: dancing on the precipice

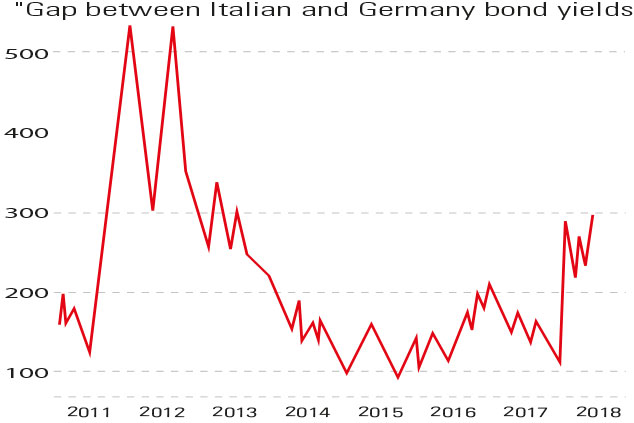

Like Greece in 2011, Italy has too much debt (about 130% of GDP) and a populist government that wants to spend more money than the European Union (EU) wants it to. Unlike Greece, Italy is "too big to fail", so its politicians feel able to push the EU harder than Greece did. The risk, of course, is that markets lose faith in the ability or willingness of the European Central Bank to underwrite all this, particularly as current boss Mario Draghi steps down next year. The indicator to watch is "lo spread", as the Italians put it the gap between German and Italian government bond yields. As the chart shows, the spread on ten-year bonds is near its highest level since 2013.

China: a rival reserve currency?

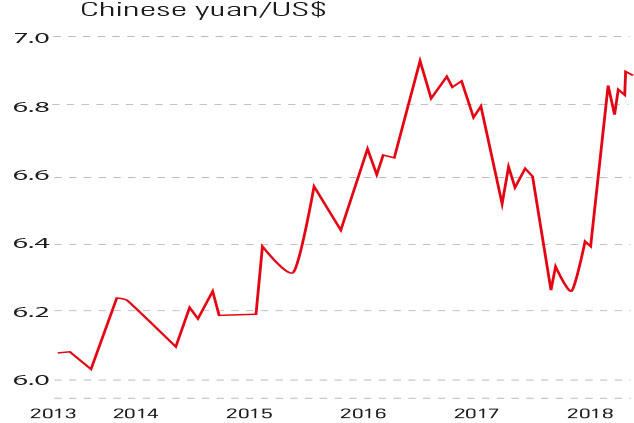

The trade war between the US and China, combined with America's increasing willingness to "weaponise" the dollar's reserve currency status by effectively locking nations and individuals out of the financial system, may in the longer run create a space for the Chinese yuan to operate as a rival reserve currency. That would mean the development of a "whole new monetary order," notes financial historian Russell Napier, one as key for today's investors "as the breakdown of the Bretton Woods agreement was for their predecessors". Watch for the yuan falling below seven to the dollar.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how