What Dr Copper is telling us about China’s tough balancing act

The price of copper has tumbled as China's leaders struggle to keep their economic plan on the road. John Stepek explains why that matters for your money.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Copper has had a torrid time of it recently.

The price has tumbled by nearly a fifth in the last couple of months alone.

So what's the problem? And should you be worried about it?

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why copper is considered a good leading indicator

Copper is sometimes described as Dr Copper by investors. The joke goes that it's the metal with a PhD in economics. When copper looks sickly, it spells bad news for the global economy.

Why? Because copper is used in everything. Every car that rolls off the production line, every building that's wired for electricity, every piece of computer kit they all need copper. So when global economic growth is strong, demand for copper should be high. And when it's weak well, copper is one place that this weakness should show up.

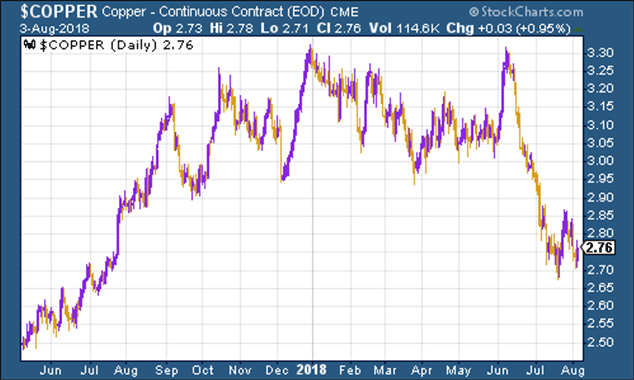

So it's worrying that the price of copper has fallen hard this year. It's down by nearly 20% in the past couple of months alone as the chart below shows.

(Copper price since May 2017; Source: stockcharts.com)

John Dizard in the Financial Times a columnist I have a lot of time for even argues that investors should be very wary indeed. "Take the hint," he says. "Copper tells you this is not the time to put on more risk."

So what's the problem with copper, and how worried should we be?

One word, I think, can sum it up for now: China.

China has been trying to rein in the amount of risk in its financial system. The country has a huge volume of bad debt. The last thing the Chinese authorities want is for the country to have to ride out a 2008-style financial crisis. That's why the boss of the central bank warned of a pending "Minsky moment" last year.

There's also the issue of soaring property prices. As we know from our own experience, nothing stokes social tension like a large swathe of your population being unable to afford to buy a home in their own capital city. So the Chinese would also rather stop property prices from booming and get away from this idea of property as a "can't lose" investment.

The problem is, they hadn't reckoned on dealing with an escalating trade war at the same time. China feels that it could probably deal with the problems in its financial system, as long as exports were doing OK. But with the US threatening tariffs on every Chinese import it consumes, that's not the case.

So China's leaders are now in a sticky situation. That's why, alongside the copper price, the Chinese stock market has suffered a precipitous fall and is now in a bear market (having fallen by 20% from its most recent high).

China's tricky balancing act

So the questions now boil down to: will China act to offset the slump? And will that action have any effect, even if it does?

As Diane Choyleva of Enodo Economics points out, the answer to the first question is "yes". Beijing is already going easier on the banks for example, banks are effectively being allowed to lend more than they were previously, particularly to small businesses. They have also increased public spending, with tax cuts and the issuance of special bonds to finance local government infrastructure plans.

However, says Choyleva, "we think Beijing will keep the real estate market on a tight leash". So we're not (yet) looking at a "stimulus" along the lines of the one that flooded the globe in 2008.

The yuan has also fallen, which helps China's exporters. Whether this is entirely deliberate or not is hard to tell. As John Authers points out in his FT email this morning, it's easy to fall into the trap of imagining that China's leaders are uniquely clever, long-term thinkers, with a grand plan that they are trying to put into place.

The reality, of course, is that they're just human, like every other politician around the world. And while China might be a dictatorship, it's a dictatorship run by committee. So there are a lot of views and cliques and conflicting interests to be balanced.

In short, there's no more reason to expect them to get this right, than you'd expect our own politicians (for example) to surprise us with their competence.

So to sum up: China has been trying to rein in harmful and wasteful credit growth which has led to colossal mal-investment (ie, money being pumped into projects that will never repay their investment).

In doing so, they knew that they might slow their economy (and drive several low-quality companies and projects into bankruptcy), but they thought they could handle it. And to be clear, China is starting to rebalance its economy the consumer is becoming a more important driving force. But a US trade war has thrown a spanner into the works.

So what's next? As Choyleva puts it: "Beijing has a tough balancing act to pull off".

If they pull too hard on the reins, then the potential for a financial crisis in China grows. That would be deflationary for the entire world. While I'm still an inflationist, a proper China crash is probably the main scenario under which I'd revise that view.

If they loosen too much in the hope of postponing any pain (or once it gets too much), then you get an inflationary surge, but also a build-up in even more financial fragility.

This is one of those things where we'll just have to keep an eye on it. There are a lot of moving parts what will Trump do next? How tight is Xi Jinping's grip on power right now? When it's all about the politics and the egos, there's a lot more room for misjudgements.

We monitor the copper price every week in Saturday's Money Morning, and we'll be paying more attention to China generally. But for now, that's probably the best advice I can give. Invest as you were, but be aware that this is a potential issue.

By the way, if you want to understand why you shouldn't necessarily extend China's woes to the whole of emerging markets (though Latin America won't like falling copper prices), then you should read this week's MoneyWeek magazine cover story. Subscribe here now if you haven't already.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?