We all live in Greenspan’s dystopia now

It’s important to emphasise just how important former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan has been in shaping our current screwed-up financial system, says John Stepek.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Former US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan told Bloomberg this week that there isn't a bubble in stocks. Instead the bubble is in bonds.

As you may know by now, I'm often among the first to have a pop at Greenspan. And I'm going to do it all over again now. Because if we're going to pay attention to what he says, then I think it's important to keep emphasising just how extensive his role in shaping our current screwed-up financial system has been.

Then we'll get on to evaluating his argument.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So, Greenspan. He's the King of Moral Hazard. While he was at the Fed,he often talked about the market knowing best. He used this ideology as a reason to block sensible reforms, arguing that the market would take care of fraud or over-exuberance.

And you know, I have some sympathy with that view of the market. Markets are an excellent way to allocate resources efficiently. They are an extraordinarily effective way both to gather together all available information and to incentivise the best course of action, given that available information. Like democracy, it's not perfect, but it's better than any other method we've found.

The problem is, it only works if the incentives cut both ways. If your money is genuinely on the line, then you will evaluate risk as thoroughly as you can. If it's not, then you will skew to the upside. As a result, your markets will be bubble prone and will encourage huge resource misallocation.

And that's what Greenspan did. Heused his own ability to manipulate markets (via interest rates) to ensure that the rules of capitalism only applied on the way up.His consistent message to the financial industry was: "You keep your profits, and the taxpayer will pick up the losses," and they heard it loud and clear. Everything was skewed to the upside, and that meant that in effect, everything was skewed to the benefit of the financial industry.

It's astonishing, by the way, that his faith in the power ofmarket scrutiny wasn't at all rattled by an embarrassing experience he had before he became Fed chairman. Little bit of financial history here. In 1984, a small savings and loan (the US equivalent of a building society) called Lincoln was taken over and turned into rapidly growing, highly-leveraged bank (there are vague parallels with Northern Rock if you want to draw an analogy).

In 1985, as a private sector economist, Greenspan was employed by Lincoln to write letters to the regulator to argue for the bank to be exempted from various rules on making risky investments with too much borrowed money. The request was denied, and even so the bank blew up in 1989, and had to be bailed out by taxpayers.You can read more about it here.

But while Greenspan did nothing wrong in the legal sense, his confessions of naivety at the time sound exactly like the ones he made after 2008.

Paraphrasing, Greenspan is always the man whose only crime was to be "one who trusted not wisely, but too well". An honest man constantly disappointed in the self-seeking actions of those around him.A man who spends half his career hanging around with government officials and yet somehow retains his faith that human beings will generally do "the right thing".

And for Greenspan to talk about bubbles now is really rich. As Fed chairman he excused his lack of action to do anything about the tech bubble by claiming that it is impossible to identify bubbles on the way up. Better, he said, to let bubbles inflate and then clear up the mess afterwards. We saw how that worked out.

I struggle to understand Greenspan the man. I suspect that he's really just a career player who said whatever it took to keep the powerful people around him at any given point happy. The Wizard of Oz made flesh.

And I also think that his legacy has done more to destroy faith in both markets and the capitalist system than any other living human being. If the free markets baby gets chucked out with the crony capitalist bathwater at some point in the future, a lot of that will be down to Greenspan.

Anyway. Now that that's off my chest...

I don't think Greenspan's wrong on the bond bubble. I've been saying for a very long time that if there's a bubble asset, it's in bonds, not stocks.

He's now backtracked somewhat and said that he's not going to put a timeframe on it. It might be like his "irrational exuberance" speech, where he said in 1996 that the stock market might be getting overexcited about tech stocks - clearly it took a while for that forecast to come good.(So maybe we should wait until Greenspan turns bullish on bonds before we call an end to bubble).

But here's what he told Bloomberg: "By any measure, real long-term interest rates are much too low and therefore unsustainable. When they more higher they are likely to move reasonably fast. We are experiencing a bubble, not in stock prices but in bond prices."

That sounds pretty sensible to me. Here'swhere I'm not convinced about his argument. Greenspan frets that we're going to see stagflation'. That is, slow growth and rising inflation.

What I'm wondering about is a full-blown punchy recovery with wage inflation and all the other stuff that everyone actually wants. That might sound uncharacteristically positive, but it would also make life tricky.

What would force the Fed to raise interest rates? Stagflation is something that they can afford to "look through" - the Bank of England is already doing just that over here. A proper wage-led recovery - that would be much tougher to ignore. And it's one of the few scenarios that no one is pricing in.

And yet the jobs market just keeps getting tighter and tighter. At some point, if employers want to get the right people to come and work for them, they're going to have to pay them more.

For me, the big surprise for the market would be to learn that this recovery has just taken a really long time, because the bust was so big. And what would be interesting to see then is how financial markets cope with a genuinely hot economy that the Fed has to rein in.

It might seem like a long shot at the moment. But the market does have a mischievous way of proving everyone wrong at just the wrong moment.

The charts that matter

Speaking of which, as we go to press, the charts of the week are looking a bit out of date. I've included the 10-year for reference, but it looks as though the prices in thecharts will be a lot lower

You see, the weak dollar narrative had been continuing merrily along all week. And then today we got the US payroll numbers.

It turns out that the US added a perfectly respectable number of jobs last month, and that wage growth was perfectly reasonable too. Markets have been selling the dollar hard, and had started to get used to the idea that the economic data was poor and that the Fed was going to have to call a halt to rate hikes this year.

That no longer seems quite as"in the bag"as themarket seems to have thought. As investors digested the news through the afternoon, the dollar made a bit of a rollicking comeback.

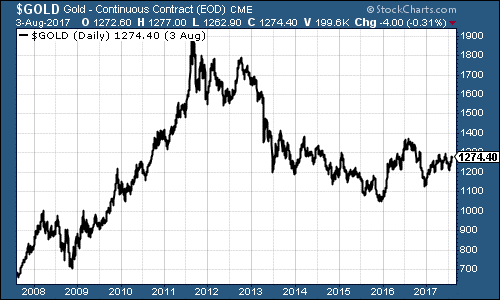

Gold

As a result,goldtook a bump lower. It closed on Thursday above $1,270 per ounce, but slipped back below $1,260 on the employment data.

(Gold: ten years)

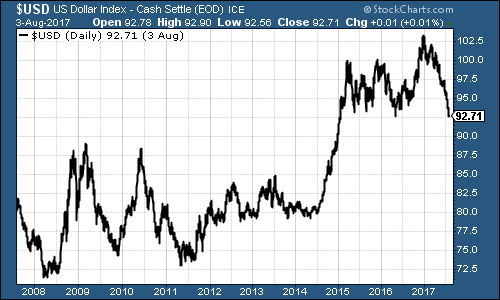

US dollar

The US dollar index made a decent rebound as it clawed back a good bit of ground against the euro. It managed to get back above the 93 mark.

(DXY: 10 years)

Again, for charting sceptics - notice that the dollar had been sliding aggressively but stalled hard at this 92/93 area. That was at a point of what technical analysts would describe as major resistance.

It doesn't mean it won't go through it. But it did suggest that this was an area where there was a high probability of the dollar making some sort of stand. When the US payrolls came in slightly better than expected (and it was only slightly better - there was nothing extraordinary about the figure) that was enough to kick off a pretty striking rally.

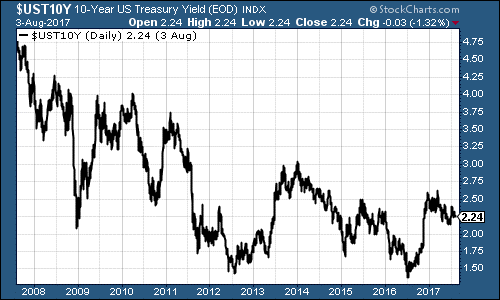

Ten-year US Treasury bonds

The ten-year yield didn't move much this week, but it did tick higher on reaction to the more positive news on jobs.

(Ten-year US Treasury: ten years)

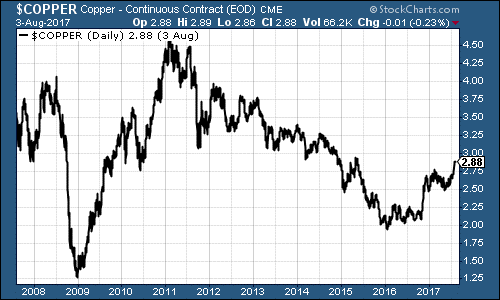

Copper

Copper struggled a little as the dollar rebounded, but this was offset somewhat by the implication that the US economic outlook isn't as bleak as perhaps it had seemed.

(Copper: 10 years)

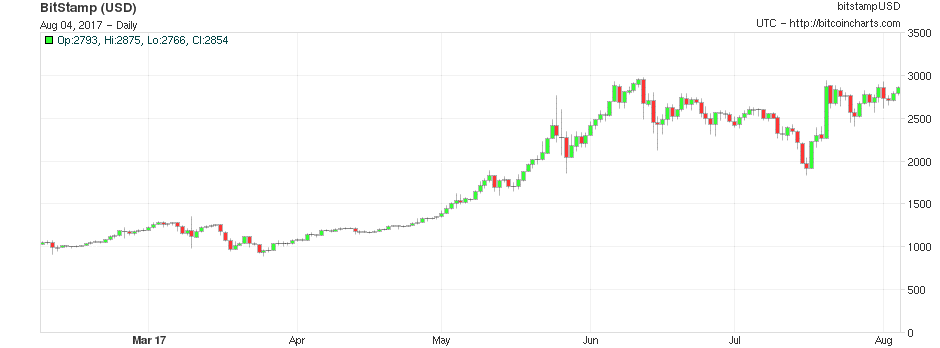

Bitcoin

Bitcoin has had another reasonably calm week, with a fork' in the crypto currency doing very little to worry its holders.

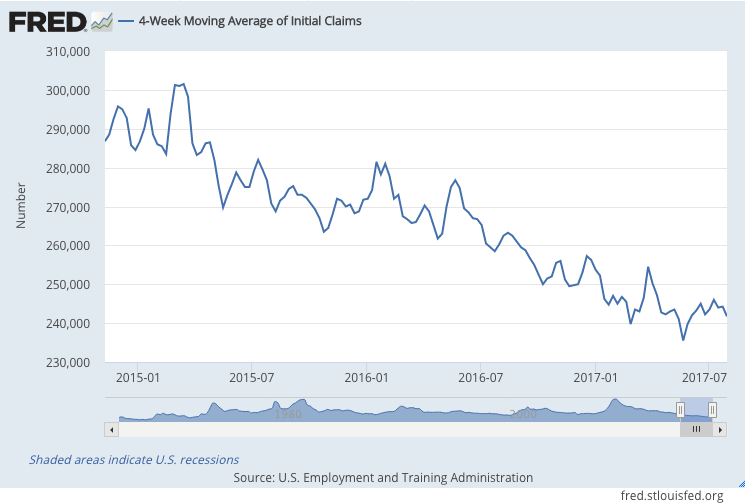

US jobless claims

The other big US jobs indicator is the weekly US jobless claims data.David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff reckons this is a valuable leading indicator.When the figure hits a "cyclical trough" (as measured by the four-week moving average), a stock market peak is not far behind, and a recession follows about a year later.

This week, US jobless claims came in at 240,000. The four-week moving average edged lower to 241,750, having hit its lowest level of the year on May 20th.

If that holds as the cyclical trough, then if Rosenberg is right (and to be fair, it's a small data set) we might be looking at a stock market peak later this year - but it looks quite possible that the numbers could get even lower.

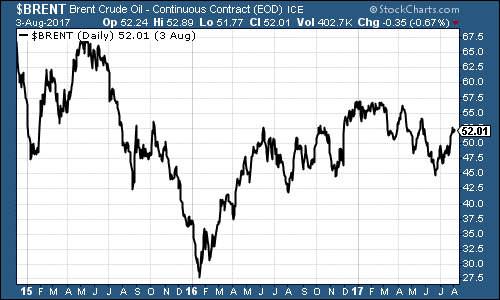

Oil price

Chart number seven is the oil price (as measured byBrent crude, the international/European benchmark). Oil has continued to rally this week, remaining above the $50 a barrel mark.

(Brent: three years)

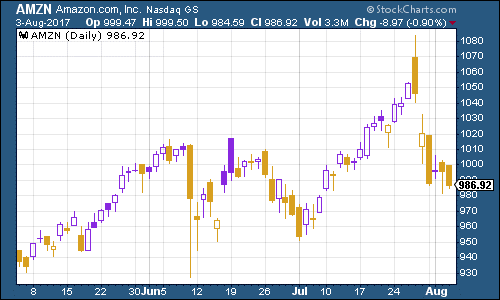

Amazon

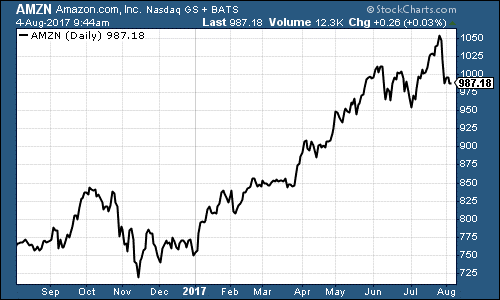

Finally there's Amazon. The tech sector giant has seen its share price struggle since its last set of earnings disappointed investors. Will disillusionment with the big tech stocks creep in? It's worth keeping a close eye on.

(Amazon: three months)

(Amazon: a year)

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Can US small caps survive the software selloff?

Can US small caps survive the software selloff?US stocks have made their worst start to a year since 1995 relative to a global benchmark. But experts think some sectors of the market are still worth buying.

-

Review: Eliamos Villas Hotel & Spa – revel in the quiet madness of Kefalonia

Review: Eliamos Villas Hotel & Spa – revel in the quiet madness of KefaloniaTravel Eliamos Villas Hotel & Spa on the Greek island of Kefalonia is a restful sanctuary for the mind, body and soul