Why I voted for Brexit

The ideals of the Enlightenment support Britain leaving the European Union, says Edward Chancellor. Not the other way around.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

By the time you read this, we'll know whether Britain has voted to remain in the European Union or not. Here's why, with a certain trepidation, I voted for Brexit. My unease derived not from a fear that change would unleash economic turmoil. Rather, I worried that this vote conflicted with my own cosmopolitan leanings. On reflection, I decided that by rejecting the EU I showed greater fellow feeling for the citizens of Europe and was more faithful to the continent's highest ideals, than those who wish to remain.

Dealing with the economics first, leaving the single market would certainly create uncertainty. But developed economies have withstood far greater shocks. US growth, for instance, was only temporarily set back by the Great Depression. It's inconceivable that a far less extreme event such as Brexit could by itself permanently damage Britain's prospects. In reality, the greatest economic risk comes from the threat of retaliation by our erstwhile European partners. Given that Britain runs a large trade deficit with Europe, a trade war would be irrational. It reflects poorly on the EU that the threat should be credible.

But doesn't a vote for Brexit reveal a petty nationalism, at odds with modern progressive values? Or, as the daughter of a friend put it: with my vote, I was putting myself in bad company. I don't believe so. At university, I read 18th-century European history. The ideals of the Enlightenment a preference for reason over tradition, for economic individualism over state control, for toleration over bigotry, and a belief that relationships between nations should be governed by the rule of law remain close to my heart. The same notions guided the founding fathers of the postwar European project.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Over the course of its evolution, the EU has betrayed those ideals. In 1795, Immanuel Kant, who coined the term "Enlightenment" (in German, Aufklrung), wrote Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. In this essay, Kant showed profound respect for a state's separate identity: a state "like the stem of a tree has its own root to incorporate it as a graft on another state, is to destroy its existence as a moral person". The consequence of bundling states together, even when done peacefully through dynastic alliances, would be that the "subjects of the state are used and abused as things that may be managed at will".

Kant preferred republican government one which gained the "consent of citizens as members of the state" to despotism, characterised by "the irresponsible executive administration of the state by laws laid down and enacted by the same power that administers them". Kant did propose an international federation of states to avoid war, but this "would not have to take the form of a State made up of these nations". Such a super-state would not allow the existence of a free state, which by definition both made and applied its own laws.

"Each state places its majesty (for it is absurd to speak of the majesty of the people) in being subject to no external juridical restraint." The European project has morphed from Kant's international federation into something akin to the late Habsburg empire, a fractious conglomeration of nations riven by centripetal forces. The EU's form of government, in Kantian terms, can be described as "despotic" since the public's consent has not been gained. During the euro crisis, unemployment in parts of Europe has exceeded Great Depression levels.

If the EU cared for its citizens, or was properly accountable, substantive reforms would have been enacted. This hasn't happened. As a result, discontent across Europe is fostering political extremism of the 1930s variety. My vote for Brexit shows solidarity with the European public and complies with the principles of Kant, the greatest of Enlightenment philosophers.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

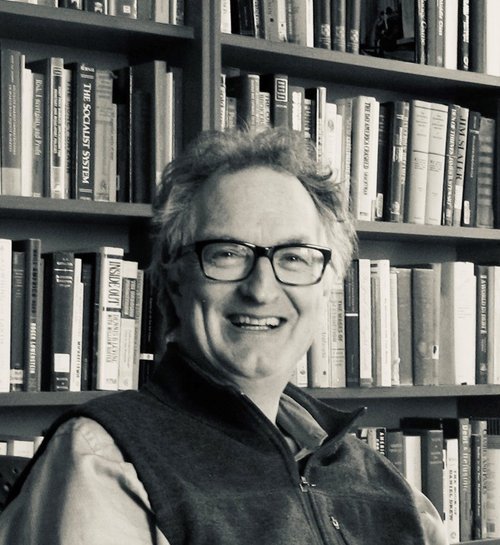

Edward specialises in business and finance and he regularly contributes to the MoneyWeek regarding the global economy during the pre, during and post-pandemic, plus he reports on the global stock market on occasion.

Edward has written for many reputable publications such as The New York Times, Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo, The Spectator and he is currently a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He is also a financial historian and investment strategist with a first-class honours degree from Trinity College, Cambridge.

Edward received a George Polk Award in 2008 for financial reporting for his article “Ponzi Nation” in Institutional Investor magazine. He is also a book writer, his latest book being The Price of Time, which was longlisted for the FT 2022 Business Book of the Year.