Should we worry about the Vix 'fear gauge'?

The Vix volatility index – the so-called 'fear gauge' – shot up in August. But, says Cris Sholto Heaton, it might not be as useful as many people think.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Sometimes a piece of market data can equally well be read as bullish or bearish depending on your preference. Consider the Vix, a measure of the volatility of S&P 500 stocks that's often referred to as the market's "fear gauge". In August, the Vix rocketed, from 12 at the start of the month to an intraday high of 50 on 24 August, before falling back to around 30 at the time of writing.

Interpretations of this move varied so much that it's difficult to believe that writers were talking about the same indicator. The spike is a bullish sign that markets are getting close to a "capitulation stage", wrote Simon Thompson in Investors Chronicle on 25 August. Not so, said Jim Edwards on BusinessInsider.com on 31 August; research by Goldman Sachs shows this level of the Vix is "usually seen only when the US is in recession".

Yet the fall back at the end of the month was an encouraging sign, thought Steven Sears on Barrons.com on 1 September; the index is "sending a keep calm and trade on' message to investors". Far from it, judging by one headline on Bloomberg.com on the same day, which read "Vix futures point to more pain for S&P 500 bulls". And so on, across the entire financial media.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

How the Vix works

An investor who took all of this at face value would have ended up rather confused. So what is the Vix? And what, if anything, is the index telling us? Put briefly, the Vix measures the implied volatility of S&P 500 index options traded on the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE).

This means that the Vix is not directly measuring the volatility of the S&P 500, but instead is based on the expected S&P 500 volatility that's currently being priced into near-term options (an option gives you the right to buy or sell a given asset in this case the S&P 500 at a given point in the future). In theory, this means that the Vix is forward-looking and reflects traders' views of the outlook for the S&P 500; hence it may have some predictive power.

Less useful than it looks

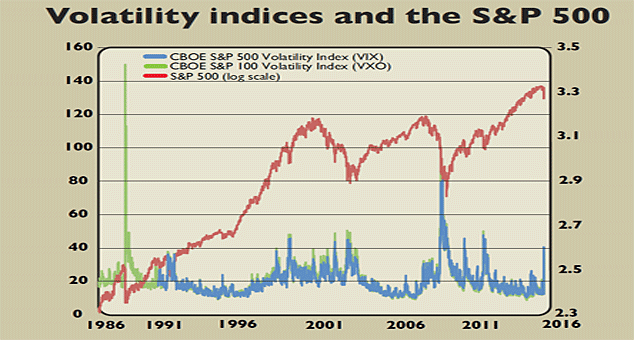

The Vix has historical data going back to 1990, while an older version of the index, known as VXO, based on S&P 100 options, has data going back to 1986. The long-term average for both is around 20, but they have swung between long periods of low volatility during steady bull markets and explosive spikes during panics: VXO hit an intraday high of more than 170 during the 1987 crash, while the Vix reached an intraday high of almost 90 during the global financial crisis.

The chart shows the relationship between the Vix/VXO and the S&P 500 (shown on a logarithmic scale in order to make large historical moves clearer). You can see how it spikes in 1987, the 1990 slump, the 2000-2002 bear market and the global financial crisis, among others. But does this give us any useful insights? In practice, no. The index consistently spikes during the sell-off, rather than beforehand: in other words, it doesn't give us any advance warning.

Nor does it reliably peak as the market bottoms: in 2008, it peaked in October, but the bottom didn't come until March 2009. In short, all that a high reading tells us is that markets are nervous something that's abundantly clear at the time. So investors can safely ignore both the Vix and all the contradictory explanations placed on it.

Why volatility ETPs are a poor hedge

The VIX was originally created as a measure of the volatility priced into index options, but it wasn't long before it evolved into a way to trade volatility. First came VIX futures and options, which offer a way to bet on the VIX rising or falling. For example, if you believe that S&P 500 volatility is likely to rise, you'd buy a futures contract or a call option. If you expect it to fall, you sell a futures contract or buy a put option.

Instruments like this proved reasonably popular as a way to hedge stock portfolios against the risk of a market decline, but their use was mostly limited to more sophisticated investors who understood derivatives markets. However, the launch of the first VIX-linked exchange-traded products (ETPs) in 2009 gave less experienced traders easy access to volatility trading. The recent spike in volatility is likely to lead more investors to consider using these products to hedge their portfolios.

But before anybody dives into using volatility ETPs, they need to be aware that holding one for more than a few days willoften lose you money regardless of what the market does. Take the iPath S&P 500 VIX Short Term Futures ETN (NYSE: VXX), for example. If you'd bought this ETP at the beginning of 2015, you'd be sitting on a loss of around 2%, even though the VIX is up by more than 50% since then.

Why is this? It's because volatility ETPs track VIX futures, rather the level of the VIX itself. These futures contracts expire monthly, so before the end of the month the ETP must roll forward into the next contract. Since next month's contract usually has a higher price than this month's one, each roll means the ETP makes a loss and erodes its value. This makes them a poor tool for long-term bets on volatility, although they can still be useful for short-term trades.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?