Should you buy into corrupt countries?

Foreign investors running have been pulling out of Malaysia after corruption allegations engulfed the country. But is corruption a reason to avoid certain markets altogether?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The last few months have been a tough time for emerging markets, with the MSCI Emerging Markets index down by more than 15% in US dollar terms since late April. But one country that has been surprisingly hard-hit is Malaysia, which is traditionally seen as relatively defensive by emerging-market standards. Stocks in Kuala Lumpur are down by 7% in local currency terms, while the ringgit has slumped almost 9% against the dollar.

That's largely due to foreign investors running for the exits: they have been pulling money from Malaysia for 14 straight weeks, the longest period of capital flight from the country since 2008, on the back of the corruption allegations engulfing the country (see below).

The slump is a reminder of how issues such as politics can have a huge impact on emerging markets. Another recent example is Brazil, where a $2.1bn graft scandal involving the state oil company Petrobras has further damaged a market already suffering from falling commodity prices and the end of a consumer credit bubble. For investors who are more familiar with developed markets and their higher standard of governance, these events can come as an unpleasant shock.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

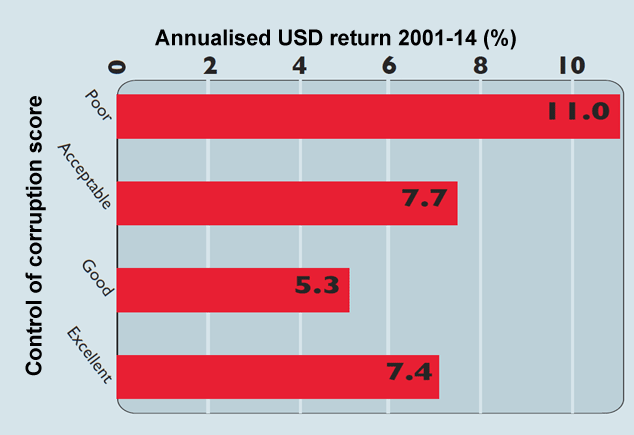

But are such risks a reason to avoid certain markets altogether? Recent history suggests not. Over the last decade and a half, investors could have made impressive returns by backing the countries with the worst reputation for dodgy dealings, according to Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton in this year's edition of the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook.

They found that between 2001 and 2014 those countries with "acceptable", "good" or "excellent" corruption scores had an average annual return between 5.3% and 7.7% in US dollar terms. But those markets with "poor" control of corruption produced an average return of 11%. On the face of it, that suggests that low standards of governance are more than priced in. Investors are unwilling to pay as much for assets in corrupt countries as they would for comparable assets in cleaner markets, so those assets are undervalued. So those who are willing to take the gamble are likely to be rewarded with higher returns.

That said, the period covered by the study was a very good one by emerging-market standards. Between the beginning of 2001 and the end of 2014, the MSCI Emerging Markets index produced annualised returns of 10.71% in US dollar terms, beating the 5.07% annualised return from the MSCI World index of developed markets. By comparison, emerging markets lagged developed markets by more than 3% per year in the previous decade. Riskier, lower-quality assets tend to outperform in boom times and give back some of those gains when the cycle turns. So it would not be surprising if the markets with the greatest problems with graft did rather better over the past decade than they will do in the near future.

What's more, even if countries with governance issues are priced to deliver strong long-term returns, they are likely to be more volatile as recent events show. So investors who don't have the stomach for shocks should avoid them. However, since the aftermath of scandals can help make markets cheaper, they can present a good opportunity for bargain hunters.For example, MoneyWeek thinks that Brazil now looks a very attractivelong-term bet.

Malaysia's farcical scandal

But in the last few weeks they have expanded into allegations that around $700m from the fund has ended up in the personal bank accounts of the prime minister, Najib Razak.1MDB was established in 2009 and rapidly accrued criticism for investment in questionable projects, lack of transparency and poor management, racking up RM42bn (£6.9bn) in debt in the process.

Earlier this year, documents emerged alleging that Jho Low, a Malaysian playboy businessman, who has links with Najib's stepson Riza Aziz, may have siphoned off money from a joint venture between 1MDB and PetroSaudi, an oil exploration and production firm. (Low and Aziz were both involved in the production of The Wolf of Wall Street, the hit 2013 film about a US fraudster.) Low denies all wrongdoing.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Mischa graduated from New College, Oxford in 2014 with a BA in English Language and Literature. He joined MoneyWeek as an editor in 2014, and has worked on many of MoneyWeek’s financial newsletters. He also writes for MoneyWeek magazine and MoneyWeek.com.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn