Should you buy 'linkers' – inflation-linked bonds?

Cris Sholto Heaton looks at how inflation-linked bonds (often referred to as linkers) work, and whether they're worth buying.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

An inflation-linked bond (often referred to as a "linker") is a bond whose payments are indexed to the rate of inflation. The way in which this works varies between bonds, but let's take a simplified example.

Assume we have a ten-year bond with a "coupon" (interest rate) of 2.5%, which is paid yearly, and a "principal" (the amount repaid at maturity) of £100. Let's also assume that cumulative inflation totals 25% by year five of the bond's life and 50% by the time it matures. Then the regular coupon payments will rise in line with inflation: the first will be around £2.5 (£1002.5%), the one at the end of year five will be around £3.125 (£100125%2.5%), and the last payment in year ten will be around £3.75 (£100150%2.5%). When the bond matures, the investor will receive a principal payment of £150 (£100150%).

Most inflation-linked bonds are issued by governments and the biggest markets are for US Treasury inflation-protected securities (Tips) and UK index-linked gilts. The main difference between UK linkers and Tips is that Tips offer deflation protection the principal can't fall below its initial value. If you buy $100 of Tips and £100 of UK linkers and we see deflation of 10%, you would get back $100 in Tips but £90 in UK gilts.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

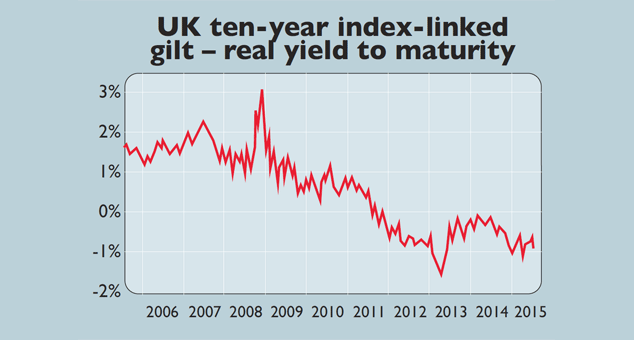

That's the basic principles of inflation-linked bonds. But how do they look as an investment today? There's no doubt they are expensive by past standards they are priced to lose money in real (inflation-adjusted) terms if held to maturity. The UK index-linked gilt maturing in March 2014 has a real yield to maturity of -0.87% (see chart). This is partly due to investors such as pension schemes, who have long-term inflation-linked liabilities and keep buying linkers to hedge these.

However, we can't look at inflation-linked bonds in isolation. They need to be compared to similar conventional bonds. Yields on these are also low, and unlike linkers they offer no protection against the rising cost of living. So if inflation exceeds a certain level, linkers could still prove a better choice for bond investors, because they would lose less money in real terms. We measure this by looking at the "breakeven rate", which is the rate of inflation at which the returns from conventional bonds and linkers would be the same. For ten-year UK government bonds, this is now 2.7%. But UK linkers are indexed to the older retail price index (RPI) instead of the newer consumer price index (CPI). RPI usually averages a bit over 1% more than CPI, so if you believe that inflation over the next ten years will average more than around 1.5% on the CPI measure, linkers could be a better bet than conventional bonds.

That actually seems quite likely, but there are still concerns. First, you need to trust official statistics many people feel they understate inflation. Second, because most UK linkers mature far in the future, a typical index-linked gilt fund has a very high "duration" which essentially means that the market value of the bonds it holds could drop significantly if interest rates rise sharply. Thirdly, if you plan to hold the bonds to maturity, you are still locking in a negative real return you're just betting they will do better than conventional bonds because of inflation.

Overall, our view is that you may want to hold government bonds as a "safe haven" they should perform well during a crisis. Linkers could make up part of that, as a hedge against inflation. But other than that, we think they are not attractive at present, just like conventional bonds.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets