The biggest obstacle to Britain’s recovery – the housing market

Britain's broken property market is the biggest threat to our economic recovery. No matter how painful it might be, we need a sharp fall in house prices. Phil Oakley explains why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

If you were to ask me to name the biggest obstacle standing in the way of a healthy UK economy, it's simple it's the housing market. Regular readers will know our view on house prices. They are too high and need to come down a lot.

High house prices, far from being a good thing, are stopping the economy from getting back on track. They suck money away from wealth-creating projects. They increase the cost of living, and make the UK an expensive place to do business.

This will not change as long as the government and the Bank of England do everything they can to keep prices high.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why are they doing this? It's because high house prices are the main thing keeping the UK's frail banking system afloat. A fresh crash in property prices would push up bad loans and hurt banks' balance sheets.

The banks know this and are using the slack that's been cut for them to build more buffers so they can cope with a day of reckoning. The trouble is, one of the best ways to do this is to cut back on lending.

This means that good businesses that could create wealth and more jobs don't get the funds they need. Either that, or any finance on offer costs too much.

So no matter how painful it would be, we need houses to fall sharply in price.

So far, that doesn't seem to be happening. House price indices show a market that is stagnant in most regions (though not all see my colleague Matthew Partridge's recent analysis to find out how far house prices have fallen in your area), rather than collapsing.

Are the government's policies are working? We don't think so. The latest survey data suggests to us that the UK housing market is like a tyre with a slow puncture. You can keep putting air into it for a while, but no matter what you do, eventually it's going to go down a lot.

The latest housing survey from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (Rics) is a good barometer of what's really going on in the market. Unlike house price indices from the likes of the Halifax or Nationwide, the monthly Rics survey is a measure of sentiment.

It talks to people on the ground the surveyors and estate agents to find out what's happening and what's likely to happen in the market. It's usually a good read.

What July's survey says is that surveyors are seeing more weakness in the market with the exception of London, which remains driven by other factors. More surveyors saw prices fall than rise in July, and more of them were in the prices falling' camp than was the case in June.

The size of the falls is so far not alarming, with most surveyors seeing price falls of 0-2%. This is consistent with most house price data. But there are some concerning bits of data.

The net balance of newly agreed sales fell to a four-year low. That's quite striking, given that four years ago the financial crisis was at its height. Meanwhile - and perhaps unsurprisingly - expectations for sales levels and prices for the next year have become more pessimistic.

One of the best parts about the Rics report, though, is that it contains lots of comments from individual surveyors. Have a read of these and you begin to get a better understanding of what's happening out there.

Apart from the well-publicised shortage of mortgage finance and the high demand for rental properties, the market is stagnating because buyers are increasingly not willing to meet sellers' asking prices. Choice quotes from the survey on this topic include:

"Vendor price expectations are still at an unrealistically high level." Anthony Webb FRICS, Cobham, Surrey.

"The key to the market is agreeing with the vendor a realistic marketing price." Geoffrey Holden FRICS, Brighton.

"The difference between seller expectations and buyers' perception of value is a serious issue." Peter Mountain FRICS, Lincolnshire.

This gap between sellers' dreams and buyers' financial limitations has been the most critical factor in the state of the UK property market for the last four years at least.

Sellers don't have to drop prices, because most aren't being forced to move. And buyers can't afford to raise their bids, because mortgage finance is short. So there's still a stalemate in many areas.

So far, there's little sign of a rising supply of properties, on the scale that might trigger a full-blown crash. Average stock levels per surveyor have not changed much during the last year.

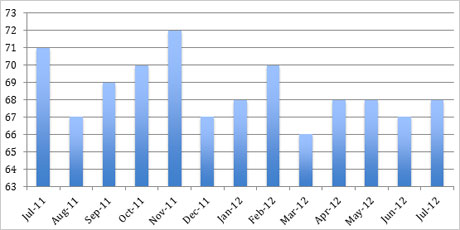

Unsold housing stock per surveyor

Source: Rics

Cheap money, mortgage forbearance schemes and government meddling are keeping lots of distressed borrowers in their homes for now. This can continue for as long as interest rates are low, but how long can that last?

The Bank of England can't print money to manipulate the bond markets forever. The scale of its existing holdings of gilts is already stretching credibility, which is why we see a bond market correction or currency problem or both eventually resulting from this policy.

The end result will be the same higher interest rates and lower house prices. As far as we are concerned, the sooner this happens, the sooner the UK economy can recover.

Recommended video

Tim Bennett looks at some of the most popular house price surveys and explains the differences between them, how they work, and how useful they are as a guide to house prices.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.