What happens to house prices when QE ends

House prices in Britain are not in a bubble, so long as interest rates stay the same. And that, says Merryn Somerset Webb, isn't very likely.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values? That, as the FT's Jonathan Eley is keen to remind us, is the question that Alan Greenspan was rhetorically asking in his famous December 1996 speech on stock markets.

He wasn't saying he necessarily saw the characteristics of a bubble, just wondering how we would all recognise them if we saw them.

He reckoned then, and mostly still does, that it isn't really possible. I'm not sure many of us who have worked through the last few decades in markets would entirely agree with him.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The tricky bit, we would say, is not identifying when things are getting very expensive by all rational criteria. That's the easy bit two weeks ago, I pointed you to the fact that all your favourite defensive stocks are horribly overpriced.

The tricky bit the impossible bit is figuring out when any particular bubble is going to burst. John Mauldin, US stock-market guru and co-author of the just-published Code Red, recently ran through a few of the things that might make it clear that some stock markets are grossly overpriced.

There's the fact that the price/earnings ratio of the S&P has risen 18% in the last year (prices are up a lot, actual earnings are not up much).There's a huge rise in margin debt (people borrowing to invest); and there are the actual prices the cyclically adjusted p/e ratio, or 'Cape', is way above historical averages in the US.

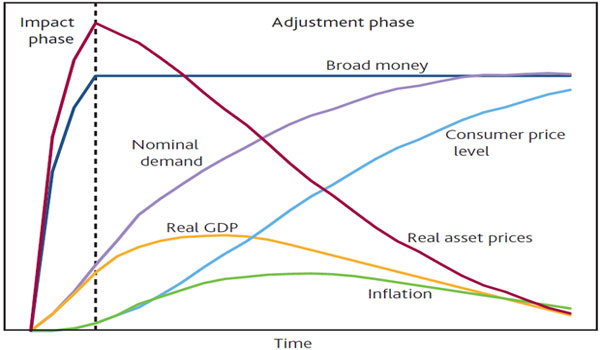

However, Mr Mauldin also pointed towards an interesting chart published back in 2011 in the Bank of England's Quarterly Bulletin. It shows what the bank expected quantitative easing (QE) to do.

In the 'impact phase' the bit when money is being created real asset prices would soar while nominal GDP and inflation would rise a little bit. So far, so obvious (in hindsight at least). But then in the 'adjustment phase', things would turn around.

Nominal GDP and inflation would rise a little more and then level out. And real asset prices would fall back to roughly where they started or at least to the point where they have not outrun nominal GDP.

The UK market isn't obviously expensive overall its Cape is at perfectly reasonable levels but look at the message in the chart and then at the performance numbers for US and UK markets, and you might start to feel a little nervous about the end of QE.

This brings me neatly, as almost everything does, to the UK's housing market. Is it a bubble, or isn't it? If you think back to the chart above, the answer is simpler than you think. As long as interest rates stay roughly where they are (we remain forever in the 'impact phase'), there is no bubble.

Bidding up property prices is entirely rational if you price houses on the assumption that mortgage rates won't rise. For those with deposits or access to the increasingly bonkers-looking Help to Buy scheme, houses are remarkably affordable: Gary Channon of Phoenix Asset Management Partners points out that on Nationwide numbers, affordability is as good as it has been for 30 years.

I'd also completely accept that the huge falls in prices in some areas since 2007 have made prices not just affordable in mortgage terms, but fair in absolute terms (try buying in Northumberland).

But that doesn't mean everything is OK. Depending on whose numbers you use, the average UK house costs anywhere from 5.5 times to just under seven times the average person's earnings. The long-term average is four times.

But there are big regional variations. A reader who I know to be exceptionally mathematically literate tweeted me to point out that in his area in Surrey, the ratio is now 14 times.

Then you can look at the speculation in the market. Mr Channon tells me that he doesn't see any. He may be right and I'd really like him to be. But we all know that there is at least some speculation.

Some areas of London are pitch black at night because no one actually lives in all the pristine new flats sold to investors. I've already come across stories of people scamming the Help to Buy system to buy an extra buy-to-let in London.

A poll compiled by Ipsos Mori for the BBC's Panorama and MoneyWeek this week found that about 45% of people asked said they thought house prices in their area were too high (a mere 9% said they were too low).

But the statistic that really stood out was this: of the people questioned who were not yet retired, 24% said that they planned to use the proceeds from the sale of property to fund their lives when they retire. That's a bad idea, and it's definitely speculation.

The impact phase for houses isn't over yet (it is being extended by Help to Buy being piled on top of the lowest interest rates for 300-odd years), but let's move on to what will happen in the adjustment phase.

The Bank's chart tells us that when QE ends, real asset prices will fall. We also know that house prices are intrinsically connected to the thing that establishes affordability interest rates. Low interest rates make payments cheap and houses expensive. High interest rates make payments expensive and houses cheap.

So when we move into an adjustment phase characterised by the normalisation of interest rates, the results should seem pretty obvious.

You may ask: when will that be? All we can really say is that when it comes to stock markets and property markets, how enthusiastically you invest has to be based on how near to the end of impact you think any market is.

The US and even the UK might be relatively near at least expectations of an adjustment phase. But the cut in eurozone interest rates to 0.25% this week surely tells you that Europe is still firmly in its impact phase. So if you must buy something, buy there rather than here.

This article was first published in the Financial Times.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your bill

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your billHundreds of thousands of pensioners will be dragged into paying income tax due to an ongoing freeze to tax bands, forecasts suggest

-

Stock market circuit breaker: Why did Korean shares pause trading?

Stock market circuit breaker: Why did Korean shares pause trading?The fallout from the conflict in the Middle East hit the Korean stock market on 4 March, with shares forced to temporarily stop trading. What is a stock market circuit breaker, and why did the KOSPI trigger one?