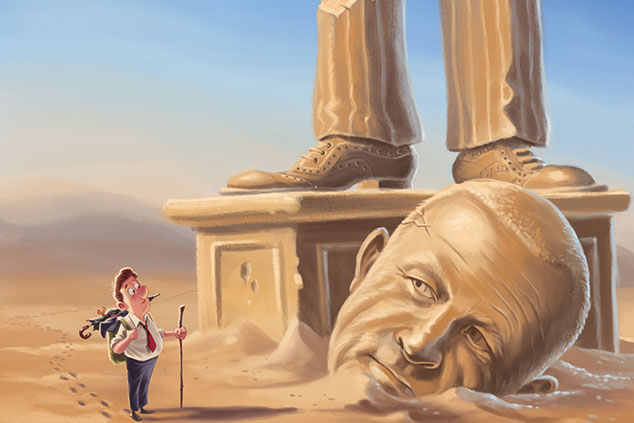

Neil Woodford’s failure isn’t just about his incompetence – it’s about much more than that

Neil Woodford’s failure isn’t just a result of poor performance, says Merryn Somerset Webb. It’s down to a failure of governance and the very structure of the fund itself.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Much of the coverage of the Woodford saga has treated the whole thing as a performance failure. He promised good returns; his investors haven't had any. But this is only part of the story and not the most important part of the story.

That's partly because active fund managers find performing well on a regular basis somewhere between very difficult and impossible. But it is also because we can't be sure yet that Woodford's newish range of funds won't in the end produce good performance. He has, after all, only had them on the go for four or five years, and in a fair world that's not long enough to judge, particularly given that today's tech-crazed growth market is not the kind he has any record of success in. The performance jury should still be out on Woodford; it isn't.

On to the most important part of the story governance and fund structure. That is what really matters here.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The fund structure bit is about holding very illiquid assets in a vehicle that offers daily liquidity (the income fund was an OEIC and this is what they do). If it takes you a month to sell a stake in a holding at a reasonable price but your investors have the right the cash on demand, times of nasty mismatch are surely inevitable (particularly when your performance is lousy). It is time of nasty mismatch that has led to the suspension of the shares (see John's Money Morning on this here).

That's why it makes sense to hold illiquid assets in investment trusts (you can sell your shares in these funds but you can't pull capital from the fund itself so investment trust managers are very rarely forced sellers), something Woodford clearly knows. The Patient Capital Trust was set up for this very reason to create permanent capital to invest in small firms without the managers having the stress of capital inflows and outflows.

The governance bit is about who should have noticed this problem building at the income fund and done something about it.

There are the wealth managers and platforms who kept supporting Woodford even when much of the rest of the market was seeing a slow-motion car crash (Hargreaves Lansdown will be having a good long think about their processes right now). There are the directors of the Woodford fund itself. And there are authorised corporate directors (ACDs), in this case also the fund's administrator, Link.

In a letter to the FT this week, James Tew of the Astewt Consultancy (I'm not convinced about the name either) notes that there should have been "ample opportunity for the ACD to prevent the more egregious circumvention of the UCITS liquidity rules", something they should have done given that they have a broad requirement to "act in the spirit of the prospectus." It would, says Tew, be a bad business if the Woodford crisis is held up as an example of the failure of the open ended structure "when in reality it is a failure of governance".

If you are wondering what the fallout from all this will be, here are some things to watch for: the introduction of non-executive, independent, investor-supporting directors for OEICs; changes to the rules about illiquid assets being held in funds that purport to provide daily liquidity to investors or indeed in any open ended funds (are commercial property investors beginning to get nervous yet?); and finally changes to the governance obligations of investment platforms providing best buy lists.

And that I suspect, is just for starters.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

"Botched" Brexit: Should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: Should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Neil Woodford’s back – but has he really learned anything?

Neil Woodford’s back – but has he really learned anything?Opinion Disgraced fund manager Neil Woodford is planning a comeback. But he doesn’t seem to have learned much from his many mistakes. So why would anyone invest with him now?

-

Neil Woodford’s back – but sometimes sorry isn’t enough

Neil Woodford’s back – but sometimes sorry isn’t enoughAdvice Neil Woodford’s funds blew up in 2019. Now he is on the comeback trail. But his apologies are unconvincing.

-

Woodford investor? Your first payment is coming soon

Woodford investor? Your first payment is coming soonNews Private investors left stranded by the collapse of the Woodford Equity Income fund will soon be getting at least some of their money back. But they will have to wait a while longer to see how much more – if any – they will receive.

-

Neil Woodford continues to cast a shadow over his successor at Invesco

Neil Woodford continues to cast a shadow over his successor at InvescoFeatures Mark Barnett, former star manager Neil Woodford’s successor at Invesco, has applied the same formula, and is struggling.

-

Is it time to buy Patient Capital Trust?

Is it time to buy Patient Capital Trust?Features Neil Woodford’s Patient Capital Trust has been taken over by asset manager Schroders. The share price has surged - but should you buy in? John Stepek looks at the trust’s prospects.

-

Neil Woodford: no silver lining for his investors

Neil Woodford: no silver lining for his investorsEditor's letter Neil Woodford made every mistake it is possible to make as a money manager. And his investors have been stiffed. But however wrong it all went, Woodford never stopped taking the fees.

-

Woodford believed his own hype – now his investors are paying the price

Woodford believed his own hype – now his investors are paying the priceFeatures Neil Woodford was once one of the brightest stars in Britain’s investment firmament. Then he came crashing down to earth. John Stepek explains what went wrong.

-

Woodford’s empire collapses – what happens to his investors now?

Woodford’s empire collapses – what happens to his investors now?Features With Neil Woodford getting his marching orders and his funds being shut down, John Stepek explains what it means for his former empire, and for those with money locked in.