Ignore the Cape sceptics

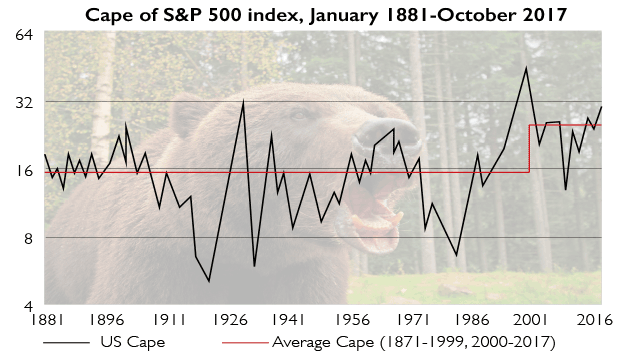

The cyclically adjusted price-earnings (Cape) ratio is an excellent predictor of long-term equity returns. And now, in the US at least, it is flashing red.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The cyclically adjusted price-earnings (Cape) ratio is an excellent predictor of long-term equity returns, not only in the US, but also across the world, say Rob Arnott, Vitali Kalesnik and Jim Masturzo in a note for Research Affiliates. It takes into account earnings over ten years, thus smoothing out the ups and downs of the business cycle. The higher the Cape the more expensive your starting valuation the lower your long-term returns. Today the US Cape is flashing red. It's reached 32, a level surpassed only during the bubble of 1929 and the technology bubble in the late 1990s. The long-term average since the 1880s is around 17.

Excuses, excuses

Whenever the Cape is high, strategists come up with all sorts of explanations for why a higher Cape is potentially justified, and thus perhaps not necessarily a sign of poor long-term returns. Cape sceptics point out that the measure has been unusually elevated since the turn of the century, averaging about 26. One argument is that there has been a structural change in corporate profitability, justifying a higher Cape.

An increase in profit margins and the share of corporate profits to GDP have been notable features of the past decade or so. Globalisation has given US corporations a boost, trade-union power has receded, while lower interest and higher leverage have juiced earnings. The past two decades have also seen a decline in macroeconomic volatility, thus justifying an equilibrium Cape of 23.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Neither of these ideas are terribly convincing, says Research Affiliates. It's far from clear that profits have reached a permanently higher plateau, justifying a higher Cape. Profit margins and earnings as a share of GDP revert to the mean. "We are sceptical that earnings can grow much in the years ahead, relative to GDP, without causing a populist backlash", especially given years of stagnant real wages. Also note that real S&P 500 earnings peaked in 2014, so the earnings upswing may already be over.

Expensive on any score

Even if lower volatility is permanent, it does not justify a Cape of 32. And markets outside the US are nowhere near US levels. The sceptics also ignore the fact that a shrinking workforce, implying slower profit growth, is an argument for a lower equilibrium Cape. "Those offering eulogies for the Cape ratio are premature as has been the case repeatedly in the past."

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how