Chinese Economy

The latest news, updates and opinions on Chinese Economy from the expert team here at MoneyWeek

-

Can Stella Li keep the Stella Show on the road?

Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

By Jane Lewis Published

-

Investors should plan for an age of uncertainty and upheaval

Tectonic geopolitical and economic shifts are underway. Investors need to consider a range of tools when positioning portfolios to accommodate these changes

By James Proudlock Published

-

How much gold does China have – and how to cash in

China's gold reserves are vastly understated, says Dominic Frisby. So hold gold, overbought or not

By Dominic Frisby Published

-

Is it time to ride the recovery in emerging markets?

Interview What's the outlook for emerging markets? Gustavo Medeiros, head of research at Ashmore Group, gives his analysis and reviews progress in developing economies

By Andrew Van Sickle Published

Interview -

The rise of Robin Zeng: China’s billionaire battery king

Robin Zeng, a pioneer in EV batteries, is vying with Li Ka-shing for the title of Hong Kong’s richest person. He is typical of a new kind of tycoon in China

By Jane Lewis Published

-

China pulls ahead of the US in the global AI tech race

The idea that China could get ahead of the US in terms of technological prowess once seemed fanciful. That’s no longer the case.

By Simon Wilson Published

-

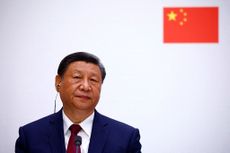

Xi Jinping masters “The Art of the Stall”

China’s Xi Jinping appears to have played his hand well in the face of hostility and threats from Donald Trump. But at home, his position may not be as secure as it seems.

By Jane Lewis Published

-

Supersonic travel: How China could 'leapfrog' US and Europe's commercial aviation industry

Opinion Innovation in commercial aviation has been stuck for 60 years. A commercial supersonic jet might be back on the market soon, but will China get there first?

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

Why Chinese stocks are so far out of favour

There’s little appetite for Chinese stocks despite low valuations.

By Cris Sholto Heaton Published