Reports of the death of growth have been greatly exaggerated

Fear of economic stagnation is wreaking havoc in the markets. But it is nothing new. We didn’t see a “new normal” in the past, and we’re not seeing one now.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

"We are suffering just now from a bad attack of economic pessimism.

"It is common to hear people say that the epoch of enormous economic progress is over; that the rapid improvement in the standard of life is now going to slow down that a decline in prosperity is more likely than an improvement in the decade which lies ahead of us."

Familiar sentiments, aren't they? It's practically a summary of today's "new normal" thinking.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Growth is dead. All the best stuff has already been invented or discovered. It's just a matter of managing the decline and hoping we all get the opportunity to die peacefully in our beds before we have to resort to cannibalism.

Of course, as you've probably already guessed sophisticated aficionado of cheap journalistic tricks that you are it's not a contemporary quote.

In fact, it's more than 80 years old

John Maynard Keynes on economicstagnation

Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

In it, Keynes reflects on the mood of misery arising from the Depression, and on why he believes the pessimism to be mistaken. He then goes on to explain why he thinks that "the economic problem" will be solved in less than 100years.

It's really a piece of whimsy rather than a serious economic analysis. In it, Keynes daydreams of a future in which most people's economic "needs" are met, leaving them with hugely expanded leisure time in which to focus on what matters (whatever that is).

It's idealistic and beguiling in some ways. But it also reeks of a snobbery towards the striving classes and the pursuit of wealth that only an individual with essentially limitless and largely unearned financial resources can luxuriate in.

Let's put that aside for now. For the purposes of this discussion, two things are interesting about this essay. Firstly, there's the fact that people were making the "secular stagnation" argument back in the 1930s. They were wrong then, and hopefully they're wrong now.

But what's even more interesting is the fact that the "new paradigm" thinking that Keynes comes up with in his piece this idea that we'll have lots of leisure time, and that our biggest challenge will be adapting psychologically to "the end of work" is also in serious vogue just now.

The idea of a citizen's income where we all get paid a living wage by the government, freeing us up to focus on what really matters (whatever that is) andthe idea that all of the world's rubbish jobs will end up being done by robots, freeing us up to do "meaningful" work (whatever that is) are seductive and scary, depending on how you look at them. But just as in Keynes' day, they don't really pass the "smell" test.

It's not different this time

The benefits system might be restructured too, though I don't think a citizen's income is practical (to get the full benefits while remaining affordable, you'd have to be so radical that no one would vote for it).

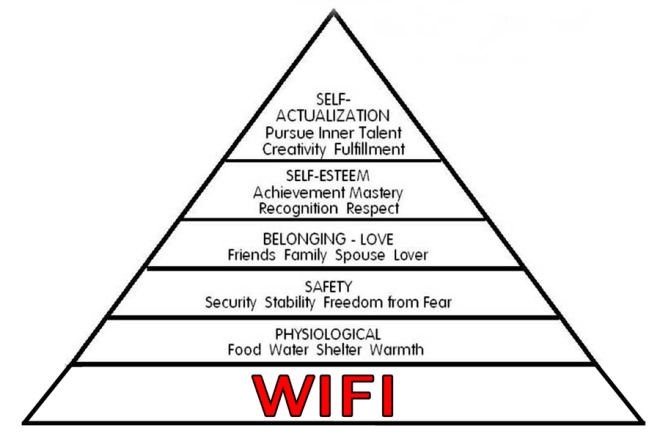

But will we do away with work? I doubt it. Our imaginations are limitless. Things that were once "wants" become "needs". One of my favourite internet memes is a diagram of psychologist Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs what it takes for a human being to be happy, basically.

It's in the form of a pyramid. At the top is "self-actualisation" where an individual is entirely fulfilled. As you go down the pyramid, the needs get less abstract and more basic. Self-esteem, a sense of belonging, safety, until at the base you have physiological needs, such as food and shelter.

In the internet-era version, some wag has sketched a new base for the pyramid, below physiological needs "WiFi".

What's my point?

Well, I've been banging on about this for a while now, but I want to emphasise it because it's important.

All of this talk of "secular stagnation', "the end of growth", and the ideas arising from it from "basic income" to "how will we cope when robots have taken all of the jobs, particularly when there's a massive mob of dreadful uneducated people who will malfunction if they have time to think" is not new.

It's symptomatic of the type of economic collapse that we've just endured, just as our current wave of populism is.

But it's having an impact on investment markets. The collapse in bond yields into negative territory is a clear sign that this "new normal" is being heartily embraced by the markets, encouraged by the actions of central banks.

And that means that any sort of recovery, when it does take hold, will be all the more surprising and all the more disruptive.

I've been reading a very interesting piece that outlines why our concerns about productivity growth are overdone, and why this recovery is not as abnormal as we might think. I'll talk about it more tomorrow.

For now, I'd just like to emphasise I don't think that concerns about the rise of the robots are entirely misplaced, and it's certainly an area that investors should be interested in.

But as with other waves of mechanisation and automation, they'll most likely be tools that create new kinds of work, rather than displacing work altogether. That's a good thing. And it means that growth and progress aren't dead.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how