The great pensions bubble

Today’s workers count the pensions they are promised as part of their wealth. Edward Chancellor explains why that's optimistic to say the least.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The US is not a "bubble economy". That's the view of the Federal Reserve, expressed by its chair Janet Yellen this month. Yellen describes a bubble as a combination of "clearly overvalued" asset prices, strong credit growth and rising leverage. However, the Fed's definition of a bubble is too narrow.

Bubbles are illusions of wealth. The last two great bubbles internet stocks and US real estate involved inflated asset prices. The great current bubble is centred around liabilities specifically pensions. Today's workers count the pensions they are promised as part of their wealth. But a look at the position of many pension schemes makes it clear that not all these claims can be paid.

Pension deficits are soaring

However, the true mismatch between pension assets and liabilities is even greater. Let's start with the assets. American corporate pensions assume an annual return of 7.1%, but will find it impossible to achieve this. The USstockmarket is expensive by historic standards. Government bonds in developed economies sport minuscule, and in some cases negative, yields. So a traditional portfolio of 60% equities and 40% bonds is likely to return a mere 2% over the long run, according to Andy Lees of MacroStrategy Partnership, an independent research outfit.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

On the liabilities side, assumptions are also "totally unrealistic", says Lees. US public-sector plans use an average discount rate of around 7.5% to value their liabilities. US corporate pension plans use a 4%-4.5% discount rate. Yet the current yield on the ten-year Treasury is less than 2%. If realistic discount rates were used, liabilities would balloon.

The consequences of the pensions bubble are already evident. Several USmunicipalities and towns have declared bankruptcy. The Pension Benefits Guarantee Corporation, the quasi-state body that insures American corporate pensions, has liabilities roughly twice the size of its assets and will run out of money in the next few years. Entitlements will have to be cut, taxes raised, and public services reduced. None of these actions will be popular.

Systematic risks

Yet underfunded corporate pensions are only the tip of the iceberg. The liabilities from unfunded government pensions dwarf everything else. Citigroup estimates that pension costs for 20 OECD countries will come to $78trn in today's money, nearly twice their reported national debt. Ben Bernanke, Yellen's predecessor at the Fed, liked to talk about the global "savings glut". In truth, there's been a dearth of saving in America and the UK since the turn of the century.

Over the past decade, US net savings have averaged little more than 1% of GDP. The collapse in the savings rate has been accompanied by declines in investment and productivity growth. All this means less money in the pot for tomorrow's pensions. The gap between the belief in those pension promises and the ability to pay looks very much like a bubble.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

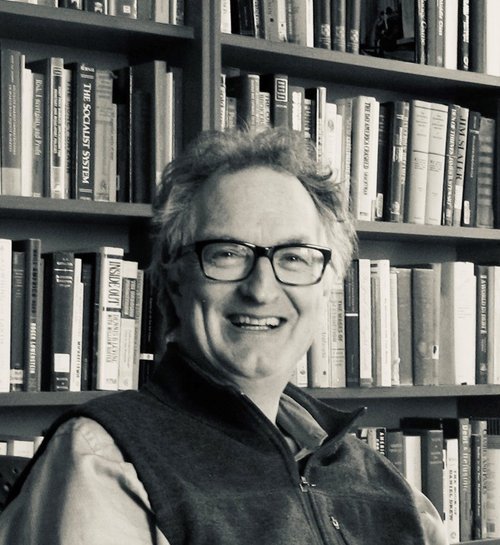

Edward specialises in business and finance and he regularly contributes to the MoneyWeek regarding the global economy during the pre, during and post-pandemic, plus he reports on the global stock market on occasion.

Edward has written for many reputable publications such as The New York Times, Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Yahoo, The Spectator and he is currently a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He is also a financial historian and investment strategist with a first-class honours degree from Trinity College, Cambridge.

Edward received a George Polk Award in 2008 for financial reporting for his article “Ponzi Nation” in Institutional Investor magazine. He is also a book writer, his latest book being The Price of Time, which was longlisted for the FT 2022 Business Book of the Year.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King