Why it pays to cut a loss

Even long-term investors should have a clear philosophy for deciding when to cut an investment. Cris Sholto Heaton explains why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Many investors never use stop losses. They tend to view them solely as a tool for short-term traders who often use leverage (borrowed money) and can be wiped out by a few big, ill-timed losses. If you're investing for years ahead, your portfolio is diversified and you don't use leverage, the threat from the odd big loss doesn't seem vast.

However, even long-term investors should have a clear philosophy for deciding when to cut an investment. If you buy a stock that drops 50%, it's possible that the market is overreacting but it's more likely that you made a bad decision. In that situation, you could hang on and hope for a turnaround, you could sell, or you could buy more. So which is the smartest bet? A recent book by fund manager Lee Freeman-Shor of Old Mutual provides some interesting insight.

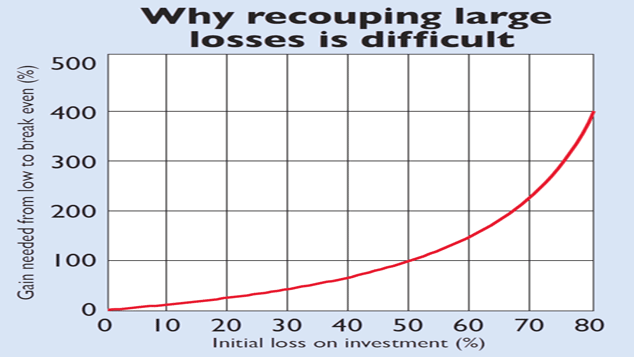

Freeman-Shor studied how the different managers that his multi-manager "Best Ideas" fund invested in coped with losing trades. He found that investors who simply hung on performed worst, because the turnaround rarely came. Out of 1,866 investments in total, 946 lost money and 131 of those lost more than 40% before they were sold. Some of those 131 stocks recovered strongly after the manager sold, but just 21 doubled and none made it back to break even (if a stock has fallen 50%, it needs to double to get back to break even see the chart above). So if you take a big loss, the odds are against you.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Managers who sold when their stocks fell by a fixed amount did much better. The key was to sell at a level that avoided severe losses without being caught out by short-term volatility. Set the stop loss too high and the chances of bailing out of a share that would have made money was much greater: out of 421 trades sold for a loss of up to 10%, 249 would have gone on to be profitable. Given that average annual volatility for the UK market over the past ten years has been around 20%, somewhere between 20% and 30% probably makes sense any stock that falls by more than 30% in a year is being abnormally volatile.

Interestingly, the most successful managers were those who sometimes bought more when the shares fell, rather than always selling. However, this is risky (you can end up throwing money at a share as it enters long-term decline) and requires investors to be ruthless about ditching stocks when they no longer have conviction. Either way, it's clear that doing nothing is rarely the best move.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Adventures in Saudi Arabia

Adventures in Saudi ArabiaTravel The kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the Middle East is rich in undiscovered natural beauty. Get there before everybody else does, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026