Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

p {font: 0.928em verdana, arial, sans-serif;}

Welcome back. In a moment I'll tell you all about a great long-term investment that could more than double your money and as a cherry on the top, it's in the banking sector. Imagine being able to tell your mates down the pub that even during the great banking crisis of 2008/09 you doubled your money in fact, it's the kind of story you'll end up telling your grandkids!

But first a quick update on last week`s tip Snam Rete Gas (Milan: SRG). Unfortunately the stock did not sell off in the last two days of the rights issue and remained in a narrow range between €3.23 and €3.30, meaning we didn't get the chance to buy in.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

My suggestion now is to keep the stock on the radar screen just in case, and watch what happens in the next weeks. The buying levels remain the same €3.10 and €2.90 providing the wider market does not sell off. If it does fall to a point where I reckon it's worth buying, I'll send you an email alerting you to the fact. However, the catalyst now for the downwards move is gone, so it may not happen.

But in any case, it was useful to learn what this strategy is about there will be plenty more rights issues in the future. And as I said in last week's issue, capital preservation is the most important thing. There will always be other opportunities your main goal should be to ensure you have the money available to take advantage of them.

And with that in mind, it's on to this week's tip

How to make money from not-so-bankrupt banks

For this trade, it helps to understand how a bank works. In particular, you must understand banking balance sheets, and how a bank finances itself.

A bank's business model is pretty straightforward. It borrows money at one rate of interest - from depositors in savings accounts, or from other banks, for example. The bank then lends that money to someone else at a higher interest rate. In addition, it has capital raised from shareholders and bond holders. So a simplified version of a bank's balance sheet looks like this:

table.ben-table table { border: 3px solid #2b1083;font: 0.928em/1.23em verdana, arial, sans-serif;}

th { background: #2b1083; padding: 10px 5px;color: white;font-weight: bold;text-align: center;border-left: 1px solid #a6a6c9;}th.first { border-left: 0; padding: 5px 2px;text-align: left;}

tr {background: #fff;}

tr.alt {background: #f6f5f9; }

td { padding: 5px 2px;text-align: center;border-left: 1px solid #a6a6c9;color: #000;vertical-align: center;}td.alt { background-color: #f6f5f9; }td.bold { font-weight: bold; }td.first { border-left: 0; text-align: left;}

| Deposits | Loans to customers |

| Interbank loans | Mortgages to customers |

| Tier 2 capital (upper and lower) | Interbank Loans |

| Tier 1 capital | Row 3 - Cell 1 |

| Equity capital (part of the tier 1 capital) | Row 4 - Cell 1 |

Let's focus on the liabilities. I have listed them in order of seniority in other words, if a bank goes bust, depositors get paid before anyone else.

Definitions:

Equity capital is the value of ordinary and other shares which cannot be redeemed and which are not required to pay dividends, which are outstanding.

Tier 1 capital is the value of ordinary shares outstanding, plus all tier 1 securities issued by a bank.

Tier 1 securities are bonds and other preferred shares that pay a set amount of interest each year. Interest payments can be suspended without triggering a default, but if interest is deferred the bank faces restrictions on activities such as paying dividends or buying back shares. They are also perpetual they don't have a set redemption date. Don't worry about the jargon for now - we'll talk more about these features in a moment.

Tier 2 capital is split into two types: upper tier 2, which takes the form of perpetual securities similar to the ones described above, but with added seniority (in other words, they get paid before tier 1); and lower tier 2, which are just normal bonds with a set maturity date.

All of these together form the so-called capital of the bank the buffer that can absorb losses.

The credit crunch destroyed faith in banks and that's left one asset class looking cheap

While the economy was in good shape, no one worried about the banks' capital. The focus was all on the profitability of the banks, and measures such as return on equity, return on assets and dividend payouts. But as we know only too well, when the economy turned sour, attention suddenly focused on the amount of capital each bank was holding and its ability to absorb losses.

The bailout engineered by the Labour government focused on injecting more tier 1 capital into the banks, first in the form of special preferred shares and later in the form of equity capital. The general feeling was that nationalization would be a last option.

Before I go on, you should know that I'm coming at this trade with a few assumptions. For one, I think that the worst of the banking crisis seems to be over in fact, the government may already have done enough to resolve the problem. But even if it hasn't, it seems likely to me that it would provide further assistance to any banks that need it in the future.

If I'm right, then there's a class of securities that has been sold off in the wake of the crisis, which could now represent a great investment opportunity.

These securities provide very good yields; the safety of a nominal instrument (one that does not get diluted with a rights issue); and seniority over the equity tranche of a banking stock (meaning that the ordinary shareholders will have to be completely wiped out before these securities are touched).

I'm talking about hybrid tier 1 securities.

What are hybrid tier 1 securities?

Although technically a share, they have features that are similar to a cross between a preferred share and a bond. They have a nominal (face) value expressed in pounds or euros like a bond - generally £1,000; they do not entitle the holder to a vote at the AGM; and they have a fixed rate of interest like a bond. In the markets, they are referred to as bonds or hybrid securities.

But the most important features are as follows:

1) They are senior to the other equity (the ordinary shareholders), which means that these holders have to be wiped out before these securities lose any value.

2) They are perpetual (or irredeemable), but every issue is callable (redeemable) by the bank at a specified date. After the call date, the interest rate paid by these securities steps up this depends on the bond in question, but it's usually something along the lines of Libor + 3%, payable each quarter. (Libor is one of the key interest rates at which banks lend to one another).

3) The interest payment can be suspended without triggering a default, but if that is the case the issuer is restricted in certain other payments it can make.

4) Although they are perpetual it is standard practice that the bank redeems them at the first call date and pays face value for them (this is not guaranteed however).

How does this work?

As these securities are quite complex I will provide you with a couple of examples.

ISIN: XS0110562534; HSBC Capital Funding 30/6/2012; coupon 8.03%, paid in euros

This is a tier 1 security issued by HSBC, quite possibly the strongest bank in the UK and one of the largest in the world. It pays a coupon of 8.03% each year until the 30th June 2012. At that date the bank is expected to repay the capital. It is not obliged to do so, but if the bank chooses not to repay the capital, then you receive an interest payment equal to Euribor (another key interbank interest rate) + 3.65% paid quarterly. In this case HSBC can decide to redeem them every quarter.

ISIN: XS0107228024; Lloyds group 7/2/2015; coupon 7.83%, paid in pounds

This tier 1 security is issued by Lloyds Group, which is 70% owned by the UK government. It pays a coupon of 7.83% each year until 2015 when, as in the previous case, it can be repaid at par value. Otherwise it pays an interest payment equal to the five-year gilt yield + 3.5%.

Given that the Bank of England base interest rate is 0.5% and that the amount of money paid by your bank on your Individual Savings Account (Isa) or deposit account is around 2% (if you're lucky), how much would you expect to pay for these two securities, given that they're paying an 8% yield? Above or below par (that's bond jargon for more or less than the face value)?

If your answer was above par, you'd be wrong. The HSBC bond is quoted at around 79 to the par and the Lloyds one is around 46 to the par. That means you pay €7,900 for every €10,000-worth of the HSBC bond, and £4,600 for each £10,000 of the Lloyds. That means the yield is more than 10% for the HSBC bond, and more than 15% for the Lloyds one.

In the Lloyds case, if you invest £10,000 now and wait until 2015 you should have around £32,200. £10,000 buys you nearly £22,000 of stock, paying around £1,700 a year for six years you do the maths if you don't believe me!

So what are the risks?

The main risk is that the issuing bank loses so much money that it stops paying dividends or even worse is nationalized. If it stops paying dividends for one year the capital would still be intact you would only lose that dividend. Remember, if they do not pay the interest, this does not constitute a default.

If the bank is nationalized then your risk increases significantly, but there could be a chance that your capital still gets paid. Precedents are few and far between and no one really knows how these securities would be treated in the event of a nationalization, which of course increases the uncertainty around them and puts further pressure on their prices.

Past examples include Anglo Irish Bank, which was nationalized by the Irish government. In this case, holders of equity and tier 1 securities were wiped out. In the UK, there's Bradford & Bingley, where the UK government has not guaranteed the tier 1 bonds, although they still pay the coupon; and Northern Rock, where holders of tier 1 were not touched.

Now Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley were basket cases and rightly went to the wall. But I reckon the government has now done enough to get the banking sector through this mess without further nationalizations. The asset insurance scheme put in place by the Government guarantees more than a quarter of the loans made by RBS and Lloyds, so they would not have to recognize losses on such a gigantic scale. New capital has also been injected. And last but not least, there's something that almost no one else has spotted yet.

I am referring to the fact that the interest margin (the difference between the interest paid on deposit and that charged on lending) has risen from 25 basis points (or 0.25%) two years ago, to around 300 basis points or 3% now. Two years ago you were paid 5% on your deposit account and could get a mortgage for 5.25%. But today you get paid 1% on your deposit and you get a mortgage for 4%. Multiply 3% by the size of the loan book (in other words, the money lent by the bank), and you get an incredibly large figure that can be used to offset future losses.

Also in previous banking crises, from Japan in 1997-2000 to Sweden in 1990-1994 to Italy in 1991-1994, assets were gradually written down over the course of a few years. This process should be helped out by this increase in interest margin.

The three to buy

I've chosen three bonds to put into the portfolio. I've listed them using ISIN Number (the number that identifies them) Issuer, Maturity Date, Coupon, clean price, yield to maturity and currency (see below for an explanation of these terms).

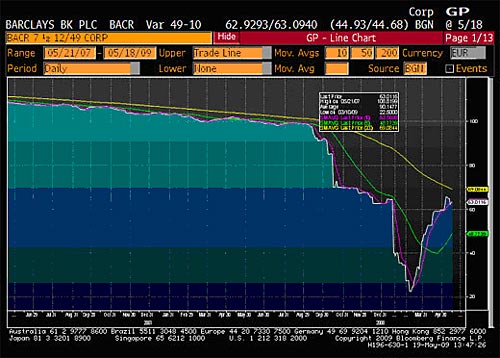

| XS0110537429 | Barclays | 15/12/2010 | 7.5 | 62-65 | 44.7% | EUR |

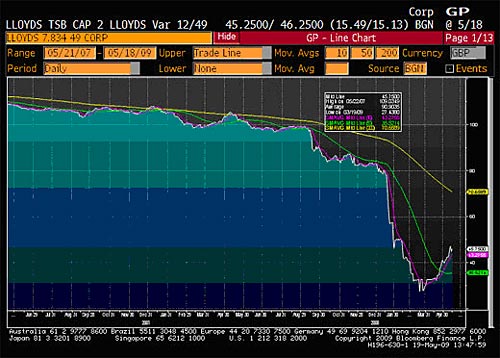

| XS0107228024 | Lloyds | 07/02/2015 | 7.83 | 45-46 | 27.7% | GBP |

| XS0284776274 | Nationwide | 06/02/2013 | 6.02 | 43-48 | 32.2% | GBP |

Barclays bond: price action over past two years

Lloyds bond: price action over past two years

Nationwide bond: price action over past two years

Now these aren't the only ones you can buy. If you are comfortable with higher minimum investment levels, and / or you can tie up your money for longer, then it's probably worth buying something that matures between 2017 and 2020, as you can earn double-digit yields for the next 10 years. If you're interested, you can find a list of other potential plays here.

How to trade them

Prices for these bonds can be obtained at www.indexco.com after you have completed the free registration process. You can then search by issuer (RBS, Lloyds, Barclays) or by ISIN number to get an idea of the various types that have been issued. The bonds can be purchased and sold by all major online brokers. But take extra caution when dealing. Ask your broker for a price quote from Bloomberg or Reuters and aim to deal around about that price. And always buy or sell using "limit orders" (orders where you place a price limit above which you are not prepared to pay). Never use market orders (orders to be executed at the best price available in the market at the time)!!!

As these are quite particular instruments, when you phone your broker always use as a reference the ISIN number or the issuer coupon and maturity date. Once you have identified them, ask your broker to contact the market maker that displays the best price (or the two market makers displaying the two best prices). Be prepared there's a good chance that you might have to trade at prices outside the spread for quantities of £10,000 or less (for example, I purchased some of these bonds quoting 16-20 and because of my small trade size I had to pay 23 for them).

And apart from these two small steps the rest is much like trading a stock. Liquidity in these bonds varies, but you should be able to deal in sizes of up to £250,000. The minimum size is £1,000 in nominal value for most of them (and the three included in our portfolio all have minimum sizes of £1,000 or €1,000). But some of the others listed above do have a minimum size of £50.000. However, remember that if you buy £10,000 nominal of a bond trading at 32, you only pay £3,200, so the 'minimums' are not quite as restrictive as they might first seem.

When to buy

Timing is of critical importance. These securities crashed in price from October last year to February this year and have rallied since then. Some are now up 40-50% from the lows they set in late February / early March. However at these prices they still represent good value for money, especially for an investor who is prepared to buy and wait for the redemption date, as some still yield more than 20%.

My advice would be to buy some now so that you secure the yield and then wait for a market correction or some other event that can push the prices of these securities down. A possible entry point would be if an issuer (British or foreign) does not pay a coupon (remember that this does not constitute a default). Such an event would clearly rattle the markets and hurt the prices of these bonds.

One more thing to remember is that these securities are irredeemable (meaning neither the issuer nor the holder can redeem them) and they can only be called, or repaid, on or after the maturity date if the issuer decides to do so. In practice however, all issuers used to pay these bonds at the first possible opportunity. Indeed, this has been the case to date with only one exception (Deutsche Bank in January). But of course, in the current climate of uncertainty, another issuer might decide not to redeem.

However, this shouldn't be a major problem because as mentioned above, after the first call date these securities usually pay a quarterly dividend based on Libor or Euribor plus some extra yield (which can vary from 1% to 4%). So if they are not called, your bond becomes a variable rate bond that can be called at every quarter. The prices of such securities should not be far off the parity of 100.

Trading risks

The main trading risk for these bonds is the spread between bid and offer, so these bonds are most suited for investors who are likely to carry them over to maturity and are happy to carry the risk. If you do need to sell in a hurry, then you will only be able to sell at the bid price, and especially for bonds trading well below par this can result in significant losses. For example, if the spread is 40-44, if you buy on the offer at 44 and you want to sell because of unforeseen circumstances, you will only be able to sell them at 40, thus resulting in a 10% loss right away. For smaller investments the risk can be even higher. Again, taking my recent bond purchase as an example, I had to buy at 23, 3 above the offer price of 20. The bid price of 16 means an even larger loss if I have to sell right away.

Volatility in these securities is also much higher than in a normal bond and is similar (although not quite as high) to the volatility of a share. They tend to be correlated to the price of the shares of the issuing bank, so expect the price of these securities to drop if the corresponding equity prices fall and vice versa.

And if you decide to invest in securities priced in euros or dollars you also have currency risk if the pound strengthens you might lose some of the amount invested (the opposite however is of course also true, in that if the pound weakens, you might make extra profit).

But let me stress again that the main risk on these securities is that the bank issuing these instrument goes bust like Lehman Bros (an unlikely event). In that case, these instruments would be worthless because they are just above the equity in term of seniority. A more plausible threat is that of the bank being nationalised, in which case these securities would likely face losses. No precedents apart from Anglo Irish Bank, Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley exist, so any outcome could be possible in the event of nationalisation, from 100% recovery to total loss.

Bond mathematics

As these securities are quite complex I will explain some of the concepts of bond mathematics.

Clean Price: this is the price of the bond without accrued interest. Prices quoted by brokers are always clean prices.

Dirty Price: this is the price of the bond with accrued interest. The dirty price is what you actually pay for the bond. For example, let's say that on the 30th June 2009, I buy a bond paying interest on the 31st December 2009 at par (100) with a 10% coupon. I will pay 100 (clean price) + 5 (the accrued interest or six months of 10% annual interest). So my dirty price (or the amount I will pay) will be 105.

Yield to maturity: this is the annual interest you will earn if you buy the bond and then hold it to maturity. It is the sum of the coupon and the difference between the price paid and the nominal value, divided by the number of years to maturity of the bond.

For example, if I buy a 5-year bond with a 6% coupon for 95, then my yield to maturity will be 7%. That's the 6% coupon plus (100-95)/5 or 1%. I paid 95% for a bond that pays me 100 in 5 years' time, so each year I gain an extra 1% in yield (in reality it's a bit more as the coupon of 6% should be divided by the price, or 6%/95 = 6.31%, but I've kept things simple here).

When bonds are trading at a fraction of their par value, the yield to maturity gets more extreme. Take this example: I buy a bond for 33 to the par (33% of face value) maturing in 10 years with a coupon of 5%. My yield to maturity in this case would be 5%/0.33 + (100-33)/10. That's 15% + 6.7% which equals 21.7%.

As these bonds are quite volatile and move more with the underlying equity than with interest rates the more advanced bond concepts of duration, Macaulay duration and convexity are not really relevant here. But if you're really desperate to learn more about bond maths and how changes in interest rates affect the prices of bonds, have a look at the following websites:

https://www.investopedia.com/university/advancedbond/default.asp

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/education/ccbs/handbooks/ccbshb20.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macaulay_Duration (use this link as the starting point of your research and investigate the other subjects at the bottom of the page).

One last thing

These securities are a little known part of the investment universe that's worth fully exploring. There are many different types of securities, issuers and seniority - this article has focused on Tier 1 securities issued by British banks, but many others exist - for example, Tier 1 securities are also issued by European banks. Then there are upper tier 2 securities and lower tier 2 securities, which do not yield as much as a tier 1 but are senior (ie they are paid before tier 1 securities). I will write more on these and similar securities in the future, as I think there are some other equally good opportunities in this area out there.

Please also be aware that I do hold some of these securities in my personal portfolio, as I think that the risk / reward profile is favourable, and I don't think the British banking sector will go bust or be nationalized in the near future. In particular I think that the market is underestimating the impact of the asset guarantee scheme, which basically transfers all the losses from the banks to the British taxpayers. So you might as well try to get some benefit from the banking sector's Government guarantee after all, you're the one who's paying for it!

Good luck with your investing.

As usual I welcome any feedback any questions and any suggestions that you might have. You can contact me at eventstrader@f-s-p.co.uk

Your capital is at risk when you invest in shares, never risk more than you can afford to lose. The share recommended is denominated in a currency other than sterling. The return from such shares may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Please seek independent personal advice if necessary.

Figures are calculated using the closing mid-prices on the date on which shares are first recommended. All gains are gross, and returns will be affected by dividend payments, dealing costs and taxes. Past performance and forecasts are not reliable indicators of future results.

Profits from share dealing are a form of income and subject to taxation. Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and may be subject to change in the future. Editors or contributors may have an interest in shares recommended.

Events Trader is issued by Fleet Street Publications Ltd. Registered office 7th Floor, Sea Containers House, Upper Ground, London SE1 9JD. Customer services: 0207 633 3600. Registered in England and Wales No 1937374. VAT No GB629 7287 94.

Fleet Street Publications is authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. FSA No 115234. https://www.fsa.gov.uk/register/home.do.

2009 Fleet Street Publications Ltd.

Contact Us:

To contact Fleet Street Publications Ltd, please send an Email to our customer services department at: cservice@f-s-p.co.uk

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how