House prices: expect the worst

In August 2005, Fred Harrison told MoneyWeek that the UK property boom would last another three years, before ending in 2008. Here he updates his forecast.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

In August 2005, Fred Harrison told MoneyWeek that the UK property boom would last for another three years, before ending in 2008. Here he updates his forecast

Recent news on the housing market has been nothing but negative (see the graph below). The International Monetary Fund says UK house prices are 40% overvalued. The Nationwide building society has cut its forecast for 2008 house price growth to 0% a fall in real terms.

Yet most remain complacent. The Ernst & Young Item Club (using the Treasury's model) reassures that "it is unlikely there will be a major housing recession".

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

However, the truth is that the consensus view on housing has been consistently wrong.

Experts predicted a modest rise in prices for 2006 in fact, as I forecast in my 2005 MoneyWeek article there was a strong surge, with growth exceeding 10%.

Why do these experts' get it so wrong? It's because they are working with defective models, which assume that the health of the property market depends upon the condition of the rest of the economy. In fact, my research suggests that property is the key factor that shapes the business cycle, not the other way around.

My model suggests that the property market runs in 18-year cycles. There have been three in the postwar years (1956-74, 1975-1992 and 1993-2010). The operating mechanism is shown in the graph above. Earnings across the economy rose roughly in line with national income, as did the cost of building homes (including materials, and wages and profits in the construction sector). House prices, however, rose much faster, to disruptive heights, peaking in the booms that result in busts. The cause of this instability is the out-of-control rise in the cost of land. The supply of land is fixed, so when the economy is growing, it has to become more expensive. Rising land prices squeeze corporate profits, reducing the money available for wages, until prices simply can't go any higher because most people can no longer afford to buy. The phenomenal rise in land prices since 1993 is the main reason why the next downturn will turn into a depression.

That may sound extreme. After all, most of us could relax if the only issue was the trend in house prices. Negative equity will burden only those who are forced to sell properties bought in the past three years or so. But much more is at stake. Forecasters base their optimistic outlook on the belief that the "fundamentals" rule out a recession, claiming a strong labour market will offset the pain of falling house prices. In fact, causation runs in the opposite direction. The fall in house prices creates the conditions for recession, as is now clear in the US. Lay-offs in the construction industry and related sectors are curbing consumption, which discourages investment and ends in a recession.

Look what happened when the last real estate cycle exhausted itself at the end of the 1980s. In Japan, the authorities mishandled the biggest postwar boom in property prices. Bad loans to land speculators were allowed to blight the balance sheets of banks that should have been allowed to fail. The outcome? A decade-long depressed economy.

Much the same happened in Germany, and it looks like the US and the UK will make the same mistakes. In the UK, the government has already moved to underwrite Northern Rock with taxpayers' money. Reckless mortgage lending will go unpunished, leading to even worse practices in the next property cycle.

Similarly in the US, the lessons of the savings and loans (S&Ls) scandal of the 1980s were not learnt. Now Congress is heading for the safety of the hills, promising to forgive mortgage debts in a bid to deflect the heat from politicians.

I cannot forecast the depth of the looming global depression because some events are unpredictable, such as the extent to which protectionism will rear its head in the States. But a good working assumption should be: expect the worst. Sell your buy-to-lets and investing in safe haven' assets such as gold may also be a wise move.

Fred Harrison is a director of Economic Indicator Services. The second edition of Boom Bust: House Prices and the Great Depression of 2010 can be bought online at the MoneyWeek bookshop or tel 01730 233870.

Worrying times for UK homeowners

The latest data on the housing market make worrying reading for UK homeowners, writes John Stepek. Property consultant Hometrack's survey of 6,000 estate agents found that house prices fell on a monthly basis in October for the first time in two years, declining 0.1%. The annual rate of growth slid to 4.4% from 5.0% in September.

More tellingly, the Bank of England reported that the number of mortgages approved for buying a new home fell from 108,000 in August to 102,000 in September. That was 20% down on a year ago, and the lowest level of approvals since July 2005 a point where the housing market was just recovering from a year-long slump in transactions.

Recent data from the Royal Institution for Chartered Surveyors show that new buyer enquiries are falling sharply, moreover research group Capital Economics believes that the Rics data suggest new mortgage approvals will fall "well below the 100,000 mark by the start of 2008" a decline not seen since the sales collapse in 2004. It seems that Fred Harrison's prediction of a slump beginning in 2008 could well be accurate.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Who will follow Sri Lanka into a debt crisis?

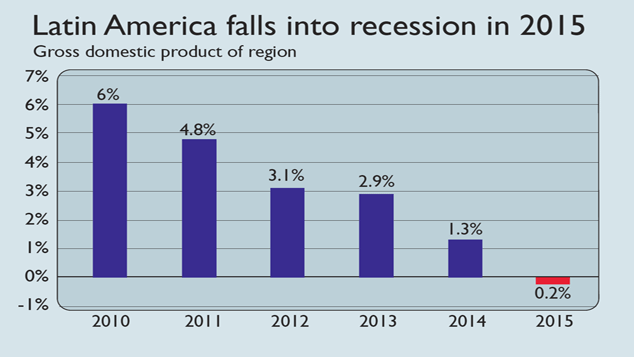

Who will follow Sri Lanka into a debt crisis?News Sri Lanka defaulted on its debt in May as soaring global food prices and a tourism slowdown collided with years of profligate state spending. Which countries could follow?

-

The emerging-markets debt crisis

The emerging-markets debt crisisBriefings Slowing global growth, surging inflation and rising interest rates are squeezing emerging economies harder than most. Are we on the brink of a major catastrophe?

-

Make money from the metals mining boom in Latin America

Make money from the metals mining boom in Latin AmericaTips Covid-19 has hit Latin America harder than any other. But the continent's highly competitive mining sector looks poised to profit handsomely over the next few years. James McKeigue explains

-

Why Vietnam is the star of Southeast Asia

Why Vietnam is the star of Southeast AsiaEditor's letter Emerging markets should be a good source of income in the years ahead, with emerging Asia looking most appealing, and Vietnam the standout performer.

-

Latin America’s best markets are in the bargain bin

Latin America’s best markets are in the bargain binTips The Andean Three – Chile, Peru and Colombia – should have little trouble shrugging off the pandemic, says James McKeigue. And their long-term prospects remain excellent.

-

Brazil: an attractive long-term bet

Brazil: an attractive long-term betFeatures Despite all the gloom surrounding Latin America, Brazil is an attractive long-term bet for investors prepared to take the risk, says Sarah Moore.

-

Protect your wealth from the all-powerful bankers

Tutorials Gold is the best insurance against economic collapse and the misuse of power by central banks. But simply holding gold may not be enough. Bengt Saelensminde explains why it's essential to diversify your gold holdings, and outlines the best ways to do it.

-

How much higher can gold go?

How much higher can gold go?Features With governments and central banks intervening in the currency and bond markets on a daily basis, it's little wonder that jittery investors are being drawn to gold - it's one of the few 'free' markets left. But how much higher can it really go? John Stepek investigates.