Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Investors have continued to flee emerging markets. In the week to 29 January, $6.3bn was pulled out of emerging-market stocks. That's the biggest such withdrawal since August 2011.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index has lost almost 7% this year, with some individual markets suffering double-digit declines.

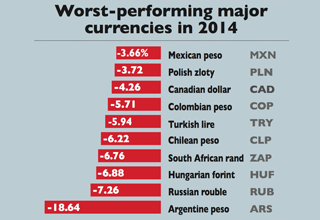

Meanwhile, many emerging-market currencies have been battered, diving against the dollar (see below table for the hardest-hit major currencies). Interest-rate hikes by several central banks did little to stem the tide.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The tide goes out

In the past few years, all the money created by Western central banks has sought juicy returns in emerging markets. Now money is starting to flow back to the rich world as the US Federal Reserve tapers its money-printing programme.

The tapering process is seen as a prelude to an eventual rise in US interest rates, making risky, emerging-market assets less attractive.

In countries where local politicians have rattled investors, or foreign capital has been squandered on blowing up a consumer boom rather than, say, invested in infrastructure such as Turkey rates usually have to rise even higher to keep foreigners around.

Rates will have to rise yet further before the sell-off dissipates, says Citigroup. That's because the returns investors are getting are still too low, adjusted for inflation. India's real' interest rate is still negative and South Africa and Indonesia's barely positive, for instance.

Markets are discriminating

The good news is that investors have differentiated between economies that have got their act together and tackled reforms, such a Mexico, and poorly run states such as Argentina. As a result, emerging markets look less vulnerable to a late 1990s-style crisis.

Still, while the fundamentals may not merit a domino-style collapse, "once investors start to sell in order to get ahead of the crowd, they become a crowd", as Breakingviews' Edward Hadas puts it.

Two things could trigger this kind of across-the-board panic, reckons Free Exchange. More countries could face social upheaval, making necessary reforms (or even higher interest rates) impossible, thus undermining investor confidence.

A second factor could be "a sense that the emerging economies are fibbing about the state of their financial systems" after credit booms in several states, banks and companies could be dodgier than they appear.

But so far, at least, it's not 1997 all over again and the slide has yielded buying opportunities.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026Podcast Fidelity's Tom Stevenson reveals his top three funds for 2026 for your ISA or self-invested personal pension

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now