A risky play on the housebuilders

The housebuilder rally is built on sand, but it’s good for a short-term punt, says Phil Oakley

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Apart from the buoyant London market, which has attracted a lot of foreign money, Britain's housing market is a tough place to be. Houses remain unaffordable for many would-be buyers, and it's still hard to get a mortgage unless you have a large deposit.

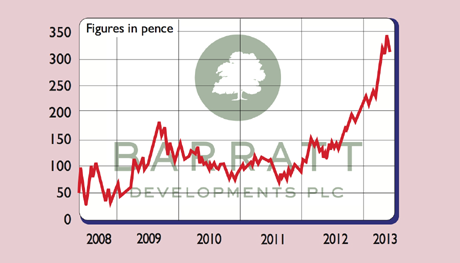

You'd think this would have made life difficult for Britain's housebuilders. But it hasn't. The profits and share prices of the quoted sector are soaring, largely as a result of massive government subsidies. I hadn't expected our politicians to be quite as relentless in their support for the sector and, as a result, have been much too cautious on it. But for how long can profits and share prices keep going up? Is there still time to jump on board?

Housebuilders are in clover

As the table below shows, the past year has been fantastic for housebuilder shareholders. Many have doubled in value, or more. With hindsight, there are lots of reasons why this has happened.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

| Persimmon | 1,194p | +140% | 17.10 | 2.07 | 12.08% | 22.00% | 22.93% |

| Barratt Dev | 320p | +180% | 22.86 | 1.48 | 6.48% | 15.10% | 60.00% |

| Taylor Wimpey | 98p | +143% | 16.90 | 1.60 | 9.45% | 8.80% | 31.03% |

| Berkeley Group | 2,127p | +77% | 14.79 | 2.33 | 15.73% | 17.80% | 19.68% |

| Bellway | 1,288p | +85% | 15.24 | 1.34 | 8.82% | 16.10% | 25.92% |

| Bovis | 765p | +92% | 19.17 | 1.35 | 7.04% | 12.00% | 34.84% |

| Crest Nicholson | 349p | N/a | 14.19 | 1.96 | 13.82% | 19.30% | 18.70% |

| Redrow | 224p | +105% | 18.67 | 1.45 | 7.74% | 14.60% | 36.67% |

First and foremost, the government wants house prices to go up. The finances of British banks are still vulnerable to falling house prices, and the government also sees housebuilding as a way to stimulate growth in the economy. So it has launched plenty of schemes to prop up the sector. In March 2012, the government launched New Buy an initiative where the government and housebuilders provided shared equity loans to first-time buyers who couldn't come up with the deposits needed to get a mortgage. This has helped housebuilders to sell a lot more houses, without having to cut selling prices.

Things have got even better with the recent Help to Buy scheme. Here, housebuilders don't have to contribute a penny. The government is using taxpayers' money to guarantee 20% of the value of a mortgaged house (up to a value of £600,000). This will support up to £130bn of fresh mortgages, putting an estimated £12bn of taxpayers' money on the line. It's no wonder that in recent weeks housebuilders have been talking of rising reservations and increased interest in new houses.

Better yet for builders, the supply of new houses isn't rising fast enough to keep up with all this government-funded demand. This is a recipe for higher selling prices and profits. In 2007, the top of the last boom, around 200,000 new houses were built each year. Persimmon reckons only 110,000 will go up in 2013. Finally, the housebuilders are still sitting on parcels of cheap land that they either bought during the last recession, or have written down to realistic values. As this land gets built on and prices keep rising, there's scope for the builders to make bigger profits.

With these three factors set to stay in place for a while, betting against the rally looks foolhardy. City analysts expect profits to keep booming during the next couple of years and argue that this is what justifies their current share prices.

So what could go wrong?

In short, a lot. Too much debt being taken on by people who couldn't afford to pay for it caused the last housing crash. Now the government wants to get the same party going again. Just like the last time, house prices are being driven up by higher borrowings, not higher wages, which come from genuine prosperity. So what happens when this taxpayer-funded support is taken away? Where is the money going to come from to keep house prices propped up? With Help to Buy, the government is taking part in a dangerous game that will be very difficult to get out of.

Yes, interest rates look like they could stay very low for a while yet. But the interest rates on government bonds have been moving higher in recent weeks

. A sharp increase in interest rates would cause a lot of heartache for mortgage holders and a big fall in house prices. I think that investing in this market is dangerous. It has all the hallmarks of a government-sponsored bubble.

That said, the government has shown that it believes the housing market is key to winning the next election. That means that both it, and the new incoming governor of the Bank of England, will do what they can to stoke the housing market for the next couple of years at least. If that happens, then housebuilders could keep on doing well.

So if I was going to take a punt on the sector now (which I'm not), I'd go for the cheapest companies in the sector. These are the stocks that are trading on the lowest multiples of tangible book value (P/TBV) and where returns on equity are still some way off their 2007 peaks, and so have room to grow further.

This leads me towards Bellway (LSE: BWY), Bovis Homes (LSE: BVS) and Barratt Developments (LSE: BDEV). Let me make clear, I believe that buying these stocks is a gamble, and a bet on continued government support for the housing bubble, rather than a sensible investment based on strong fundamentals. But if you want to take a short-term bet on the government being able to keep the party going until the next election in 2015, this is the way to play it.

Verdict: a risky short-term bet

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026Podcast Fidelity's Tom Stevenson reveals his top three funds for 2026 for your ISA or self-invested personal pension

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now