How to invest in gold

There are a number of ways you can invest in gold, from buying the yellow metal directly to investing in a gold ETF or buying gold-mining stocks. We look at the pros and cons of each strategy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

With a history stretching back to the dawn of civilisation, investing in gold is perhaps one of the most tried-and-tested economic transactions you can make.

Gold’s recent history has also been a prosperous period for gold investors. Strong demand from various sources has driven global gold prices to new all-time highs early in 2026.

On 12 January, the price of gold crossed the $4,600 barrier for the first time. Geopolitical tensions had ramped up following president Trump’s intervention in Venezuela the previous week.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

And it is high-stakes US politics that have pushed gold on to its latest high, as Trump has made global investors jittery over the independence of the Federal Reserve (Fed) by opening criminal proceedings against the central bank’s chair, Jerome Powell, in connection with his recent testimony on renovations to the Fed’s building.

“This is being interpreted as part of an ongoing campaign by Trump to strongarm the Federal Reserve into lowering interest rates,” said Tom Bailey, head of research at HANetf. “For investors, this raises fear that the Federal Reserve’s decades-long independence is at risk. This potentially undermines the credibility of the dollar and dollar-denominated assets, increasing the appeal of gold.”

Gold outperformed the S&P 500 in 2025 for the second calendar year in a row. If you are considering where to invest for 2026 then an allocation to gold may well be tempting.

There are various ways that you can add gold to your portfolio. These range from buying gold bullion to investing in a gold ETF.

We take a look at the pros and cons of each approach.

Gold investing for beginners

If you’re just getting started in investing, it’s worth considering the role that gold could play in your portfolio. It’s tempting to buy gold during a bull run like the one it has been enjoying, but even when gold prices aren’t climbing there are good reasons to include an allocation in your portfolio.

“Gold can be a highly effective hedge against governments’ monetary and fiscal profligacy (monetary debasements and currency devaluations) and tends to become the ultimate safe haven when global geopolitical shocks start to occur,” says James Luke, manager of the Schroder ISF Global Gold Fund.

Traditionally, bonds are used to diversify a portfolio away from equities, the theory being that when bonds underperform, stocks overperform, and vice versa.

However, as Luke explains, bonds have shown a greater degree of correlation with equities in the current market. As such, gold currently offers a greater level of protection against a downturn in equities markets, given its lower degree of correlation.

Despite this, most investors are relatively underweight gold. “We absolutely believe gold deserves a place in investors’ portfolios,” says Luke. “In our view a traditional 60:40 portfolio would benefit from diversifying 10% into a gold allocation.”

How to invest in physical gold

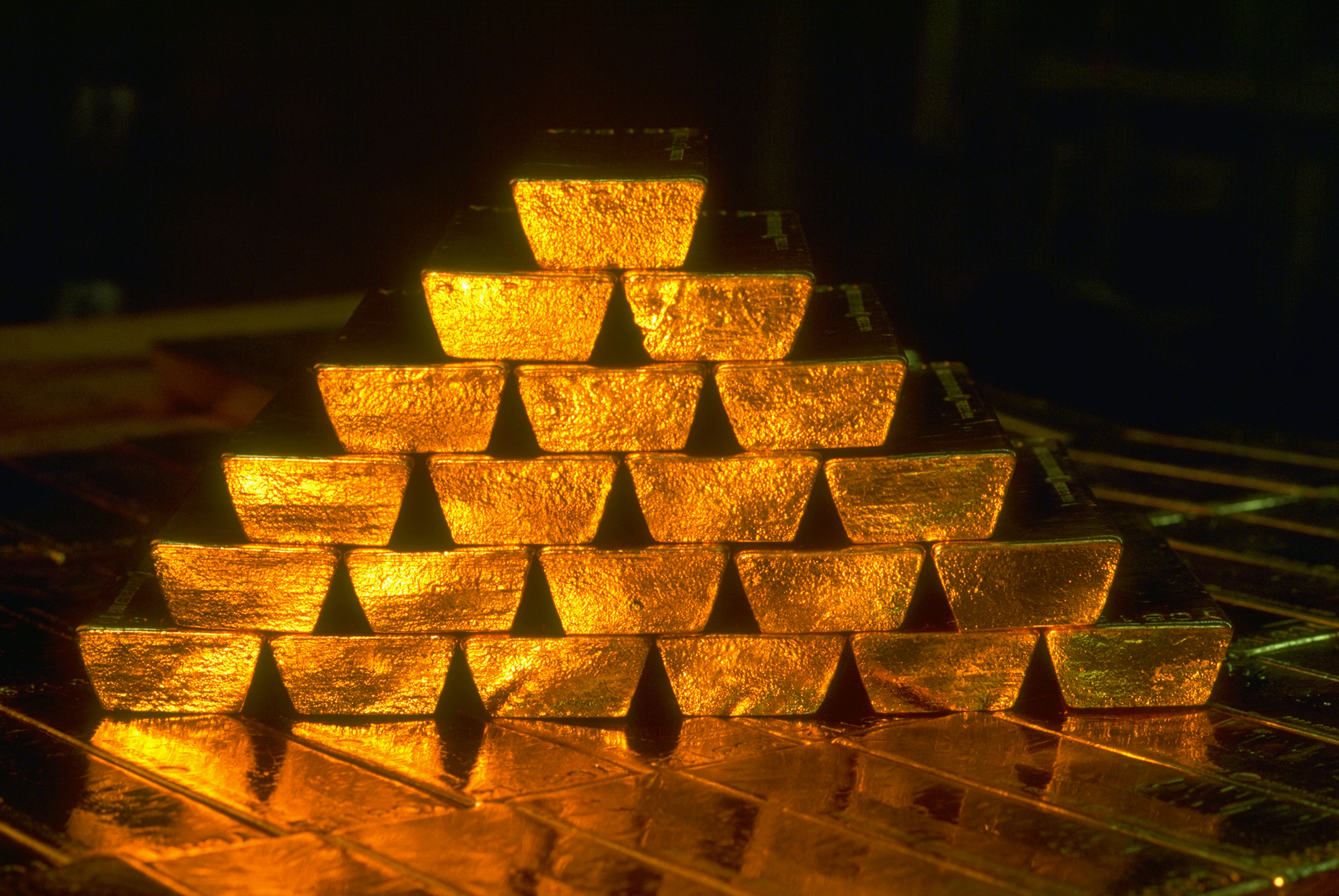

One way to add gold to your portfolio is by buying physical gold in the form of gold bars and gold coins. And though it isn’t usually purchased for investment purposes, bear in mind that any gold jewellery you buy will store value in the same way that other gold investments will.

Physical gold can be purchased from government mints such as the UK’s Royal Mint, precious metal dealers such as Sharps Pixley or GoldCore, and jewellers.

It is an unregulated market so you should be careful to avoid scams. One way to protect yourself is to always check whether a dealer is part of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), which sets standards across the industry.

Buying gold bars or ingots is one of the most direct ways to invest in gold.

As with any investment, it is important to do your own research on prices. Gold dealers make their money by selling for more than the spot price and buying for less. The difference – or spread – will vary depending on the gold content and weight of the bullion, who you buy from, and current supply and demand.

Gold coins can have more value than bars as they may be rarer and are often viewed as collectables, known as numismatic coins. Some forms of gold coin are tax-exempt, as they are legal tender. That means you won’t incur capital gains tax (CGT) if you sell them for a profit.

As attractive as buying a gold bar or coin may be, you should also consider the cost of delivery, insurance and secure storage. One solution may be using an online investment service such as BullionVault, which lets you invest in gold bars or coins which are stored in its vaults. The Royal Mint also has a digital option that lets you invest in physical gold, silver or platinum based on monetary value instead of weight. It can then be stored in the Royal Mint’s vault.

Investing in gold with ETFs and ETCs

A simpler and cheaper way to invest in gold is through exchange-traded funds (ETFs) or exchange-traded commodity (ETC) products.

Analysts typically favour physical-backed ETFs or ETCs, such as iShares Physical Gold (LON:SGLN), over leverage-style products that rely on derivatives, adding extra complexity.

“An ETC owns physical gold and tracks the price,” says Ben Yearsley, investment director at Shore Financial Planning. “It’s as close as most people get as it’s simple and can be held in your SIPP and ISA.”

The main benefit of using ETCs to invest in gold, according to Paul Syms, head of EMEA ETF fixed income and commodity product management at Invesco, is their simplicity and cost-effectiveness.

“It’s low cost, and [an ETC] trades throughout the day,” he says.

The main costs of investing in gold ETFs will be the ongoing charge and any platform fees. You won’t actually own any gold directly – although The Royal Mint Responsibly Sourced Physical Gold ETF (LON:RMAP) allows investors to exchange shares for physical gold coins or bars.

Owning a gold ETF or ETC will allow you to benefit from any growth in prices. Of course, you will also lose money if the gold price drops.

Take a look at our article on the best gold ETFs for more information.

Investing in gold miners

Rather than buying actual gold, you could consider backing the companies involved in gold exploration or mining. This would mean buying shares in gold miners. This requires significantly more research than tracking the gold price, as a company’s success will be linked to its exploration activities, business strategy and management.

“Many investors believe that gold mining stocks essentially give you a leveraged play on the gold price – sometimes they are right, sometimes they are wrong,” says Ben Seager-Scott, chief investment officer at Forvis Mazars.

While investing in gold miners can come with greater reward, there is also the risk of incurring greater losses.

Investors should also pay attention to the size of the company, says Evangelos Assimakos, investment director at Rathbones Investment Management.

“Smaller companies will usually have a greater proportion of their operations in mines that have yet to start production and thus carry more execution risk should their plans get pushed further into the future or see a reduction in expected output,” he explains.

Rather than picking individual gold mining stocks – which can be more volatile compared to physical gold or gold price trackers, and therefore carry greater risk – you could select a fund consisting of gold miners. For example, the L&G Gold Mining UCITS ETF (LON:AUCP) tracks the Global Gold Miners Index, and as such holds companies like Agnico-Eagle Mines (LON:0R2J) and Newmont (LON:0R28).

The pros and cons of investing in gold

One drawback of investing in gold is the lack of income available from physical gold or through gold ETFs which don’t pay dividends.

What’s more, the price of gold can be volatile over the short or medium term, making it hard to know if you are buying at the top or bottom of the market.

However, advocates see the metal as a useful diversifier, as its value and performance don’t correlate with those of other assets. It also has a reputation for retaining its value well in periods of inflation.

“If the Dollar continues to weaken, it should also reinforce the case for holding a little gold, which has a long-established inverse relationship with the US currency,” said Jason Hollands, managing director of online investment platform Bestinvest.

Hollands added that Bestinvest's ready-made portfolios typically hold around 4.5% in gold via the Invesco Physical Gold ETC as a strategic diversifier.

Interest rates are now on a downward trajectory across most major economies, which should also be supportive of the gold price.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Dan is a financial journalist who, prior to joining MoneyWeek, spent five years writing for OPTO, an investment magazine focused on growth and technology stocks, ETFs and thematic investing.

Before becoming a writer, Dan spent six years working in talent acquisition in the tech sector, including for credit scoring start-up ClearScore where he first developed an interest in personal finance.

Dan studied Social Anthropology and Management at Sidney Sussex College and the Judge Business School, Cambridge University. Outside finance, he also enjoys travel writing, and has edited two published travel books.