Why the West must invest in defence – and you should too

We’ve got used to a world without war between major powers, but that era is coming to an end as Russia threatens Ukraine and China eyes Taiwan. Buy defence stocks while they’re cheap, says Jonathan Compton

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

A regular and surreal night-time discussion with friends at my expensive single-sex boarding school was what we would do after the four-minute warning went off. This was the public alert system, which from 1953-1992 would warn of an imminent nuclear strike by the USSR. Rather than seeking shelter, it was agreed the best course of action was to race down to the nearby girls’ high school. Given it was at least a three-minute sprint and willing partners were probably hiding away or in a shelter, the naivety of our tactical plan is obvious now. Yet even during the MAD era (mutually assured destruction, in a nuclear conflict), warfare was still conventional and consisted of throwing vast amounts of ordnance at the enemy from the land, sea and air, then putting in troops to take over. There was also a reasonable belief that the Good Guys – us, Nato and democratic allies – would win. Both of these are now in serious doubt.

Britain has been involved in armed conflict somewhere in the world every year since 1914, so the UK’s last five peaceful months since our and other forces were unceremoniously bundled out of Afghanistan are highly unusual. Politicians and military chiefs are keen that this 20-year conflict is forgotten, while muttering that “lessons must be learnt”. This guarantees that the wrong conclusions will be reached; in practice, it was an old-fashioned, conventional guerrilla war. Modern warfare is about to change radically.

China and Russia are ready to expand

Thankfully, we have not witnessed direct warfare between major powers since 1945. It would be nice to believe this will continue, but unwise. Both China and Russia are on an expansionist march for which the Good Guys are ill-prepared. Since 2008 Russia has annexed parts of Georgia and Ukraine, has made claims over the Arctic, has de facto control of Syria, will shortly reabsorb Belarus (hard on the EU’s border) and has moved “peace-keeping forces” into Kazakhstan (a country the size of western Europe) from which they are unlikely to leave. Russian president Vladimir Putin has never hidden his desire to re-establish the USSR (which included some current EU nations) and is doing so opportunistically.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

China is also on a roll. Starting quietly in 1974 by taking control of some tiny Vietnamese islands, since 2010 it has ramped up its occupation of numerous atolls and shoals in strategic locations throughout the South China Sea and has even built new heavily fortified islands. Like Putin, China’s president Xi Jinping (now ruler for life) has never hidden his desire to control the south and west of the Pacific Ocean, vital to world trade. Both leaders are patiently preparing and probing for their big prizes – Ukraine and Taiwan, respectively – because they now have the edge. Their empire building is undoubtedly a near and present danger.

On paper, Nato and its mostly democratic allies still have an immense superiority in firepower. America’s military expenditure was more than twice as much as Russia and China combined last year. Add on its allies such as the UK (which at $59bn is surprisingly just behind Russia’s $62bn) and the figure is well over three times greater. This superiority is confirmed in areas such as naval power. The US Navy’s battle fleet totals 4.6 million tonnes – more than 50% higher than the two empire builders combined. America’s 11 aircraft carriers are nearly as much as the rest of the world put together, and most of the others are owned by allies. The same superiority exists elsewhere, such as in war planes. In nuclear warheads Russia and the US are level, but since the numbers are enough to wipe out the world several times over, such counting seems pointless.

Yet, for all this superior firepower, it is looking increasingly possible that the Bad Guys already have developed conventional edges and more importantly, will soon have created a lead in unconventional warfare. On the former, two examples suffice. In October last year, China launched a low-orbit hypersonic rocket, which flew around the earth at five times the speed of sound and also released a hypersonic glide vehicle that flew back several thousand miles to a test target in China. The US intelligence service was clearly horrified, not only because they knew nothing about its development, but because their vast array of anti-ballistic missiles can only hit regular, slower trajectories. China’s rocket can swerve. Satellite pictures show China is building 200 new intercontinental rocket silos and at present, it seems the US has nothing which can shoot these rockets down. The Pentagon is clearly very worried.

Or consider tanks. Russia has long enjoyed a 2:1 superiority to America but it was rightly assumed that most of these were essentially older models and no match for the well-tried, third-generation Abrams battle tank, the backbone of the US army, or for Germany’s Leopard, widely considered the world’s best tank. Yet as with China’s rockets, in the last five years Western defence ministries have been stunned by Russia’s new fourth-generation Armata tank, which appears superior in every aspect. Production has been slower than planned but the build-up continues. The West has nothing to match it.

The cyberwarfare challenge

Even the least tech-savvy of us has become completely dependent on huge technological developments over the last 30 years, to the extent tech now encompasses our lives entirely. This Christmas I bought all my (very generous) presents online, all the drink and much of the food. Hopefully, there will soon be virtual Christmas trees and decorations. My 2017 chequebook is still nearly unused, practically all payments being online. Such small things are as nothing compared to the huge personal benefit of being able to buy shares electronically on my tablet, to access any information I want from my armchair or communicate for free anywhere in the world. However, this explosion in electronic capabilities makes much conventional warfare vulnerable.

In 2014 the Ukrainian army assembled an armoured group in a forest area to counterattack into the Russian occupied zone. They were spotted by drones. Russian forces hacked and jammed the communication systems of the Ukrainian command post, then launched rockets. Two battalions of tanks were wiped out miles from the front without firing a shot. More recently in the 2020 Azerbaijan-Armenia war, Russian-backed Armenian forces were obliged to sue for peace after Azerbaijani drones (supplied by Turkey) shredded Armenia’s main tanks and artillery. Heavy-hitting and expensive equipment knocked out by the equivalent of a home-made catapult.

Translate this to war at sea and the West’s superiority looks more of a liability. Aircraft carriers have always been large sitting ducks, which is why they tend to operate a long way from land. With a top speed of 40 mph, they are hardly racy. Multiple long-distance drone or rocket attacks from the shore, other ships or submarines will certainly get through. It is worth noting that China’s sub-building programme is huge and in number already exceeds America’s. Finally, consider an invasion. Ultimately any war requires troops in large quantities to occupy land. D-Day can never happen again or even on a far smaller scale. Why? A single nuclear shell would cripple any such mass attack. Thus conventional armies – and, it seems, especially in the West – are geared up for the most recent set of skirmishes or wars, not the next ones.

A covert war

While there will always be a need for guns, ships and planes, future wars are likely to be won almost before the first shot is fired because of our dependency on electronics and developments in cyberwarfare. In 1999, two colonels in China’s People’s Liberation Army published Unrestricted Warfare, a book on strategy that sets out how to avoid democracies’ military strengths and undermine them from within, through measures such as eroding the legitimacy of government bodies, encouraging social discord and sewing mistrust between allies – in short, to use technology for propaganda. China’s strategy has since ramped up to “rob, replicate and replace” – steal intellectual property, replicate it and then replace the (usually American) company that had been dominant.

Hence China has steadily been reducing its once-large technology gap while simultaneously undermining its adversaries’ economies. But it doesn’t end there. The next phase is to be able to disrupt and then close down an opponent’s entire economy, starting with communications. Here Russia appears to be in the vanguard. This first became apparent as long ago as 2007 when, following an argument over a war memorial, Estonia’s economy was effectively blitzed by Russian cyberattacks which seriously disrupted government internet communications, the media and online banking. This pattern has been repeated many times whenever Russia has had a grievance: Georgia in 2008, Kyrgyzstan in 2009 (to pressure the government to close an American airbase), Ukraine in 2014 (pre-invasion) and successfully hacking German government files in 2015 when it was investigating Russia’s role in the WikiLeaks affair.

A larger, more recent example – probably arising from China – is the 2020 hack on SolarWinds, a Texan software business whose systems were widely used by companies and government agencies to manage their IT systems. The hackers inserted codes that allowed them to access information and malware to close down the systems of thousands of companies and government departments. It can rarely be 100% proven that such attacks are government-led, but in the case of SolarWinds, Microsoft estimated it would have required over 1,000 technicians to create, install and operate. Moreover, it has become increasingly clear that China and Russia are more than happy to sub-contract disruption either to other countries such as North Korea and Iran, or to fund and encourage private groups from countries such as Romania – a new hot centre – to America itself.

Playing the long game

Thus, preliminary skirmishes in electronics and cyberspace will determine the outcome of future wars. Cut off the ability to communicate, turn off radar and listening devices, and hack the computers to stop ships, planes and tanks from moving or firing, then stroll in. How are the Good Guys responding? Budgets are being ramped up in the US, the UK and elsewhere, but it is impossible to know if we are behind or level. Democracies, with their focus on the electoral cycle, free press and human rights, can easily be diverted by well-placed propaganda. There is plenty of evidence that Russian-backed websites were fuelling the conspiracy fires for the QAnon invasion of the White House last year. Dictatorships can play a longer game.

There is no doubt that Russia intends to replicate the old USSR, including the annexation of the whole of Ukraine. Kiev, the capital, is almost viewed as the true heart of Russia. Nor can it be doubted that China wants to take over Taiwan, as it has repeatedly stated for over 50 years. Will this happen in 2022? Your guess is as good as mine, but my hunch is that both countries are not yet ready for a full-fronted attack. Rather, they will continue to play grandmother’s footsteps – inching forward when no-one is looking. In the case of Ukraine, Russia is about to win more concessions from Nato, whose member countries entered negotiations having ruled out direct military support. In the case of Taiwan, China also has made gains – flying an armada of warplanes over and around the country, taking warships into Taiwan’s waters and expanding its many seized island bases. In both cases, the West’s reaction has been to say they are a bit cross, then do nothing.

Capital markets are notoriously bad at anticipating major political and military shifts. World War I was wholly unexpected. Stocks were trading along merrily in early July 1914. By the end of that month, the London market (accounting for a third of all global trading) had closed, followed by the rest of the world. London did not reopen until January.

I am not suggesting a repeat, but I am certain that markets are ignoring the long game being played by Russia and China, and are underestimating, or preferring to ignore, their clear intentions for military conquest. I am not in favour of neo-imperial adventures such as Libya, Iraq or Afghanistan (especially when we lose). Probably like you, I like the way things are post the USSR collapse. But this era is changing. Rather than react like the naive schoolboy of my youth, we can at least take some protection by investing in those companies which are in the lead in defence and especially in countering cyberthreats.

Seven cheap defence stocks

Listed defence companies are cheap in part because of the trend towards better environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. While these are largely to be encouraged, the industry is going through a rather prissy, virtue-signalling phase classifying defence companies – conventional or cyber – in the same socially harmful box as tobacco and slavery. This seems a little short sighted. Hence in the UK and Europe there are no defence funds and only a handful of cybersecurity ETFs, of which the largest is the L&G Cyber Security UCITS ETF (LSE: ISPY) – I bet the marketing department was pleased with that ticker symbol. But this fund doesn’t really cut the mustard in terms of holdings in cybersecurity. In performance, it mirrors America’s Nasdaq (tech) index, which I think will be weak.

The lack of funds means investors must fall back on direct holdings, where there are many cheap choices. Moreover, they have low correlation with either local or global indices where I don’t like the outlook. In the UK I have chosen three (all of which I own). The whale is BAE Systems (LSE: BA), one of the world’s top ten military suppliers, from ordnance to submarines and cybersecurity. On a multiple of ten and a yield of 4.2% this is the one to protect the grandchildren and their wealth. More specialist is Qinetiq (LSE: QQ) which develops cutting-edge technology for defence projects as well as testing, technical and cyberwarfare products. Its largest customer is the UK military, followed by the US Department of Defence. Its forward multiple is a mere 12 times. Last is Cohort (LSE: CHRT), which is essentially all-electronics defence from surveillance to control systems.

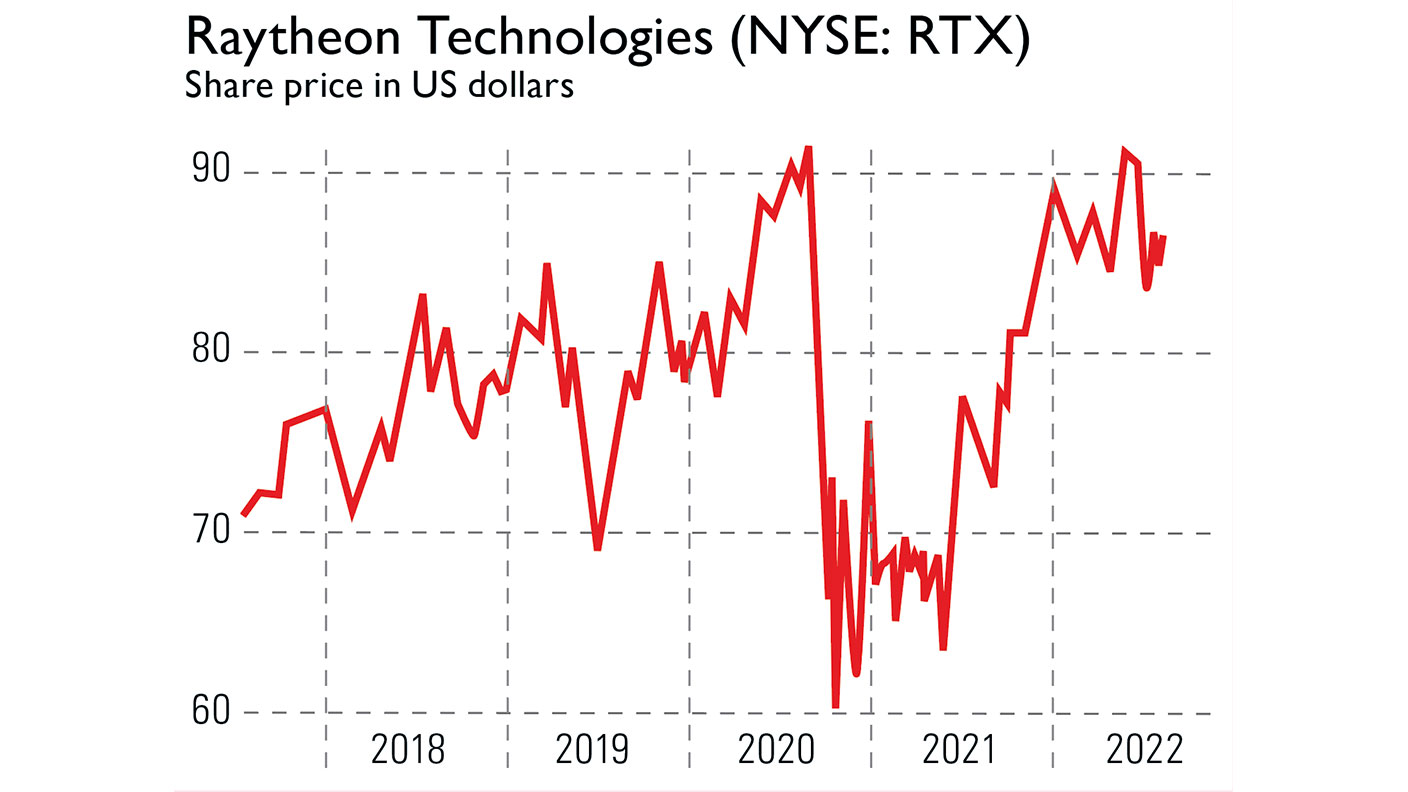

Overseas, I would stay with the larger proven groups. For missiles and rockets the number one is America’s Raytheon Technologies (NYSE: RTX), which is likely to be a key player in developing new ballistic missiles against hypersonic attack and even to take out communication satellites. For cybersecurity, Check Point Software Technologies (Nasdaq: CHKP) has a proven and steady record of growth and innovative new products.

There are two large outliers I also like. First is Sweden’s Saab (Stockholm: SAAB-B), which provides a range of military and civil security products, from aviation and missiles to radar and command and control systems. Last is Italy’s Leonardo (Milan: LDO), best known for its attack helicopters but also heavily involved in aeronautics and space defence systems. As with the others in the sector, it is cheap on a ten times multiple.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jonathan Compton was MD at Bedlam Asset Management and has spent 30 years in fund management, stockbroking and corporate finance.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Should you sell your Affirm stock?

Should you sell your Affirm stock?Affirm, a buy-now-pay-later lender, is vulnerable to a downturn. Investors are losing their enthusiasm, says Matthew Partridge

-

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategy

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategyYour pension strategy may need tweaking – with many pension experts now arguing that 75 should be the pivotal age in your retirement planning.

-

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global markets

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global marketsBeeks Financial Cloud has carved out a lucrative global niche in financial plumbing with smart strategies, says Jamie Ward

-

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracy

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracyActivist hedge fund Saba Capital isn’t popular, but it has ignited a new age of shareholder engagement, says Rupert Hargreaves

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris