Fintech: how to profit as technology transforms banking around the world

Financial technology – from apps to APIs to the cloud – is rapidly transforming financial services. This will spell doom for some incumbent firms, while others are set to win big. Matthew Partridge looks at how to find the winners.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Finance has used technology “since the days of the abacus”, as Philipp Buschmann, the chief executive of smart-banking platform AAZZUR, puts it. However, until a few years ago most financial firms and institutions remained relatively insulated from the digital revolution that had disrupted many other sectors of the economy. Even the rise of online banking had failed to challenge the dominant retail banks in the UK, while basic financial tasks such as processing payments or making cross border transactions still relied on the infrastructure created decades ago.

That’s changing – and changing fast. Customers are now much more comfortable carrying out a wide range of tasks through new channels such as apps. They are increasingly looking for the kind of convenience in financial services that they are getting elsewhere in the modern economy. The result is a fast-spreading financial technology (fintech) revolution.

Payments technology is an example where the industry is changing very rapidly, says Nina Moffatt from the fintech and payments team at law firm Paul Hastings. Until recently, companies selling goods and services over the internet had a very limited choice of providers when it came to processing payments and moving the money to their bank. However, the wider use of application programming interfaces (APIs) is now giving them a lot more choice.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

An API is essentially a way for one piece of software to communicate directly with another. Among other things, APIs make it easier for websites to use different services from multiple providers and ensure that these providers share data with each other. This means that a company selling goods over the internet can use an app provided by one firm to receive and process payments, have the money deposited into an account provided by another business and even have a link to a third app that offers credit.

Taking paperwork online

Payments technology might be experiencing a “big wave” of innovation at the moment, but other parts of the financial service industry aren’t far behind, says Michael Kent, chief executive of payments company Azimo. For example, some aspects of compliance and “know your customer” requirements “are already being automated and moving online”. Meanwhile, digital technology is increasingly being applied to payroll management and some tasks traditionally associated with a company’s chief financial officer, “which makes it much easier for small firms to deal with these tasks in real time”.

A slightly longer-term project is the digitalisation of the insurance industry. For example, Kent notes that “many underwriters are using big data – large amounts of detailed data from multiple sources – to get a much more accurate estimation of risk”. It’s true that the behaviour of the first generation of short-term lenders, such as Wonga, which was criticised for its high interest rates, “dealt a blow” to the public perception of the online lending industry. However, he argues that the successful digitalisation of consumer credit shows what can be achieved in other areas.

Build your own bank

Perhaps the biggest change to the current model of financial services comes from the rise of “embedded banking”, says Buschmann. This involves companies cutting out the middleman and “effectively creating their own bank in order to offer financial services directly to their own customers”. Some companies, such as General Electric in the US or the supermarkets in the UK, have offered banking services to their customers in the past, but this has been limited by the technological and regulatory complexity of creating their own banks.

However, the rise of digital technology, as well as firms such as Railsbank, which specialise in creating the necessary digital infrastructure, means that “the time to set up your own bank has been cut from five years to six months”. As a result, many more companies are now in a position where they should think about providing their own financial services, says Buschmann. “Just as many forward-thinking firms realised in 1999 that having a website could be extremely useful, or even a necessity, many companies are now realising that providing their own financial services to their customers is a good idea.”

Finding a new advantage over peers

The development of buy now, pay later (BNPL) services is an example of ordinary companies using a “novel customer-centric product” from non-traditional providers to gain a competitive advantage over their peers, says John Pauley of law firm Harper James. In return for the retailer giving companies such as Klarna or Clearpay a cut of the sale price, the BNPL provider pays the retailer for the goods, while allowing the customer to defer payment without incurring interest or charges (so long as the subsequent payment is made within a certain time).

Even after the fee that the retailer must pay is taken into account, BNPL ends up giving many customers “cheaper credit than traditional credit cards and much cheaper than payday loan operators”, says Pauley. So it’s perhaps not surprising that there has been a “lot of development” in BNPL, with volumes “growing significantly”, accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic as well as low interest rates. Indeed, if anything the main complaint about BNPL is that it has made it so easy to access credit that people may be using it too much – which is why the Financial Conduct Authority has announced that it will begin regulating the sector.

Emerging markets embrace fintech

Perhaps surprisingly, the fintech revolution may end up having the biggest impact in emerging markets, says Aman Behzad of corporate-advisory firm Royal Park Partners. This is because one of the problems that fintech firms have had to deal with in developed markets is overcoming apathy and suspicion from consumers in countries where “almost everyone already has credit cards and bank accounts”. By contrast, large numbers of people in emerging economies are excluded from the financial system, which means that “there’s no consumer inertia or legacy systems to contend with”.

What’s more, most people in emerging markets have mobiles and smartphones, so they are also comfortable with using online apps, says Behzad. The huge number of unbanked consumers, especially among poor and middle-income groups, combined with this “massive mobile and smartphone penetration”, means that there is a “huge opportunity” for fintech firms. Investors’ enthusiasm over this theme is shown by the hype around Brazil’s Nubank, which listed on the New York Stock Exchange last year and is valued at around $43bn. Nubank is the world’s largest standalone digital bank: it has around 48 million customers and could reach 108 million by 2025, according to forecasts by Goldman Sachs.

Behzad thinks that emerging markets can be divided into “three buckets”. At the forefront is Latin America, where you have a “massive fintech boom”, not least because many immigrants in the US are looking for a cheaper way to send remittances to their families back home. Africa is a “close follower”, with “massive amounts of capital going into payments and wallets services, especially in East Africa. Countries in Asia, notably in Southeast Asia, have been slower to adopt fintech. However, there are signs that the revolution is “now gathering momentum”, even among late adopters such as Indonesia and Pakistan.

Incumbents will come under pressure

The rise of financial technology will be good for consumers and for non-financial firms, says William Howlett of wealth manager Quilter Cheviot. They will benefit from lower prices and charges as competition and technology pushes down costs and will also gain from “an evolution in customer service standards”. However, as you might expect, the picture for the incumbent banks is much less rosy.

There are a few possible silver linings. The move to online banking has enabled banks to cut the number of branches they have to operate, with their market power enabling them to retain some of the savings “from improved cost-income ratios”. But things are going to get tougher, says Howlett. Banks “will have to deal with increased competition on pricing from the fintechs, who can offer a more nimble and cheaper service with fewer regulatory hurdles to navigate”. What’s more, the rise of fintech, and the fortunes being made by start-ups, is also hurting banking by luring the “best and the brightest” away from the industry. This is draining the pool of talent and also forcing firms to offer higher salaries to retain the staff that they will need in order to compete with other fintech companies.

The technology challenge

Indeed, banks have already found that developing digital products in-house to compete with those offered by specialist fintech firms is “tricky and costs a lot of money”, and even when they have spent the necessary funds “they have had mixed results doing it internally”, says Gary Bond, chief executive of TISAtech, which connects fintechs with financial institutions. While many top-tier banks make enough profits “to spend the necessary sums to stay in the race”, smaller banks, building societies and other financial institutions that lack such resources “can’t just throw money at the problem”.

Some firms may be able to adapt by focusing on areas such as high-end wealth management, which are less threatened by fintech since they “involve a high degree of human interaction”, says Bond. However, even such firms realise that in the longer term the saying that “if you’re not riding the wave of change, you’ll find yourself beneath it” still applies. For the smaller banks and institutions, this involves partnering with fintech firms to buy in specific capabilities and applications.

Buying the expertise

Many banks aren’t just buying particular applications, but are going further by taking over entire fintech companies. The aim is to improve their technology, create an environment that is more conducive to future innovation (in contrast to the relatively bureaucratic environments of traditional financial institutions) and even to eliminate a potential competitor. Hence there’s been a lot of mergers and acquisition (M&A) activity in fintech over the past few years, says Moffatt. Much of this has been led by banks, who are not only afraid of the threat posed to their existing business, but also believe that such takeovers make sense because “they are still better than the new entrants when it comes to providing services on a large scale”. Banks also have the advantage that they have a lot of experience with dealing with regulators, something that’s going to be an increasing issue as fintech enters the mainstream.

However, other financial-services companies have also been taking steps either to buy up other fintech companies, or at least to enter into strategic partnerships with them. For example, credit-cards and payments giant Visa was an early investor in start-up Currencycloud – a cloud-based platform for cross-border business-to-business payments – before buying the company outright for around £700m at the end of last year. Of course, while these deals may end up being advantageous for the banks and institutions, the real big winners from all this activity will be the owners and investors behind these fintech companies, especially the venture-capital firms, says Moffatt.

Supplying the infrastructure

Some non-fintech firms will also make large profits by providing the infrastructure that these new services rely upon, or by providing other services to fintech companies. Very few fintech businesses are completely self-reliant, says Moffatt. Most combine their own proprietary technology with services that come from third-party providers. With regulators set to require that fintech companies deliver much higher levels of security and governance, “those third parties that can provide a product that is not only reliable, but also ticks all the regulatory boxes, will be in big demand”.

Cloud computing is already benefitting from an increase in demand, says Howlett. Most fintechs don’t want to deal directly with the capital and storage costs of buying physical hardware, so they will continue to lease these resources. Amazon, Microsoft and Google’s cloud infrastructure will all be used by fintechs, he says, which means that they will benefit hugely from the boom in financial technology. Of the trio, Amazon’s products are “considered to be the most skewed to start-up customers”.

How to invest in the future of fintech

Investing in fintechs can be difficult because most of them are still private companies. One solution is to buy an investment trust that specialises in such companies. William Howlett of Quilter Cheviot suggests looking at Chrysalis Investments (LSE: CHRY), which “aims to harness the long-term growth potential of fast-developing companies at an advanced stage of private ownership and considering a stockmarket flotation”. Chrysalis’ portfolio holds several fintech companies, including Klarna and Starling Bank, as well as Wise (LSE: WISE), which went public in July.

European bank ING (Amsterdam: INGA). may be worth considering: it is one of the few mainstream institutions that “has had success with digital transformation”, reckons Howlett. He particularly likes the fact that it has “delivered essentially branchless banking at scale in markets such as Germany and Spain”. ING’s Australian subsidiary has even developed software that links people’s savings to their Twitter, Fitbit and Alexa accounts, allowing them to save as they “run, walk,or tweet”. It is also relatively cheaply valued, trading at only 10.6 times forecast 2022 earnings, an 8% discount to its net assets, and at a yield of 5.3%.

Howlett also thinks JP Morgan (NYSE: JPM) takes digital banking extremely seriously, as shown by its “vast IT budget”. It spends $12bn a year on 50,000 staff who focus on developing new IT applications, including a project that aims to find uses for blockchain beyond digital currencies. As well as spending large sums on in-house technology, it has also made several acquisitions, including buying UK robo-adviser Nutmeg for a reported £700m last year. It trades on 13.9 times forecast 2022 earnings, despite enjoying solid revenue growth of around 5% a year over the past five years.

Michael Kent of Azimo is very positive about firms that process payments, especially Visa (NYSE: V), which is in a good position to benefit from economies of scale. It is “definitely not complacent” about the long-term threat posed by emerging technology, he says: the firm is building up its data capabilities and even investing in several fintech start-ups. The shares trade at 25.8 times forecast 2023 earnings, but sales are growing by around 10% a year. PayPal Holdings (Nasdaq: PYPL) is the leader in online payments. While it trades at 35 times forecast 2022 earnings, revenue is growing by around 20% a year, and it more than tripled earnings between 2015 and 2020.

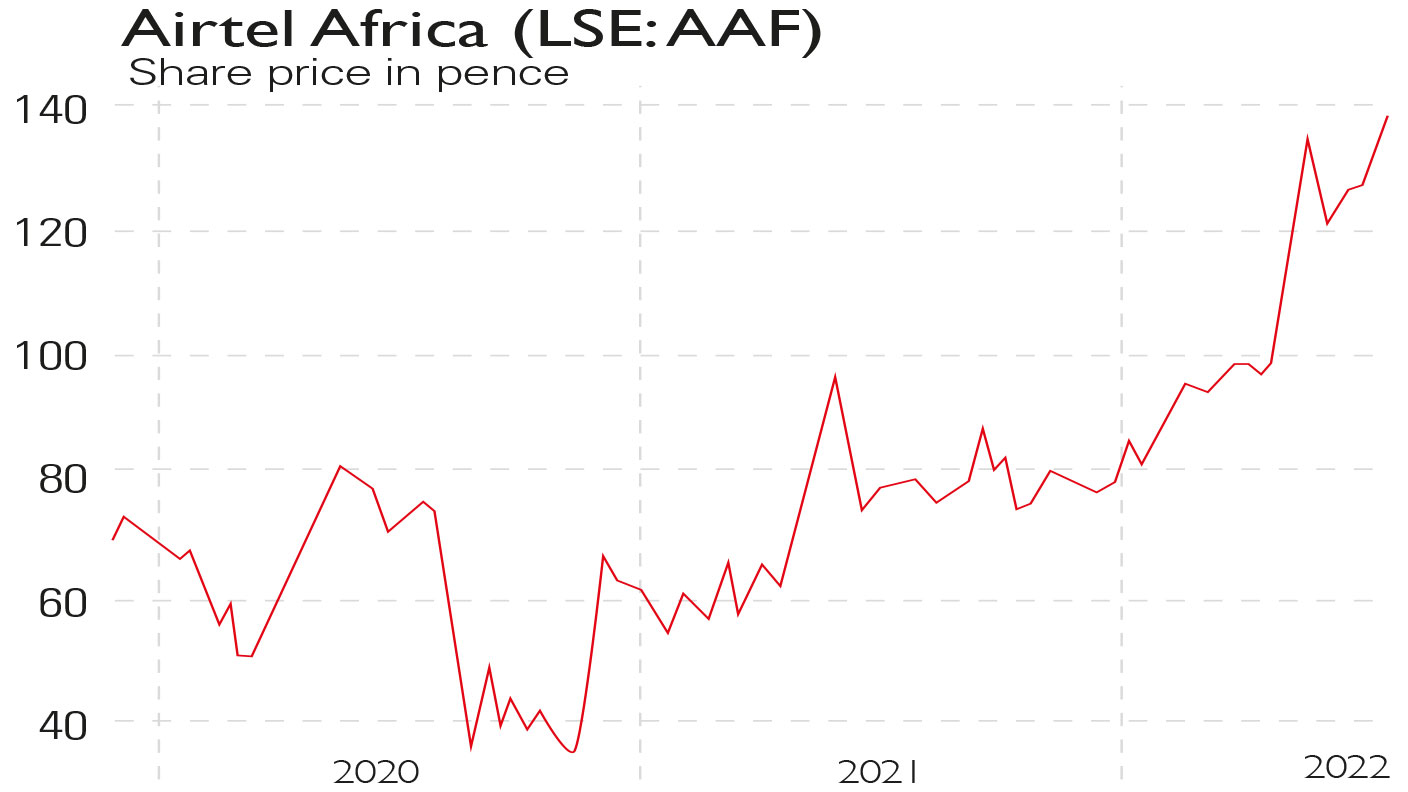

Latin America is at the vanguard of the emerging-market fintech revolution, Africa isn’t far behind, thanks to the lack of traditional banking and the rapid adoption of smartphones. The main business of Airtel Africa (LSE: AAF) is providing mobile services to around 118 million customers in 14 countries, mainly in east, central and west Africa, but it offers saving accounts, and even some loans, through a majority stake in Airtel Money (in which Visa’s main peer Mastercard (NYSE: MA) has invested). The shares have gone up since I tipped them last year, but still trade at only at 13.6 times forecast 2023 earnings.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Should you sell your Affirm stock?

Should you sell your Affirm stock?Affirm, a buy-now-pay-later lender, is vulnerable to a downturn. Investors are losing their enthusiasm, says Matthew Partridge

-

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategy

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategyYour pension strategy may need tweaking – with many pension experts now arguing that 75 should be the pivotal age in your retirement planning.

-

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global markets

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global marketsBeeks Financial Cloud has carved out a lucrative global niche in financial plumbing with smart strategies, says Jamie Ward

-

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracy

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracyActivist hedge fund Saba Capital isn’t popular, but it has ignited a new age of shareholder engagement, says Rupert Hargreaves

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris