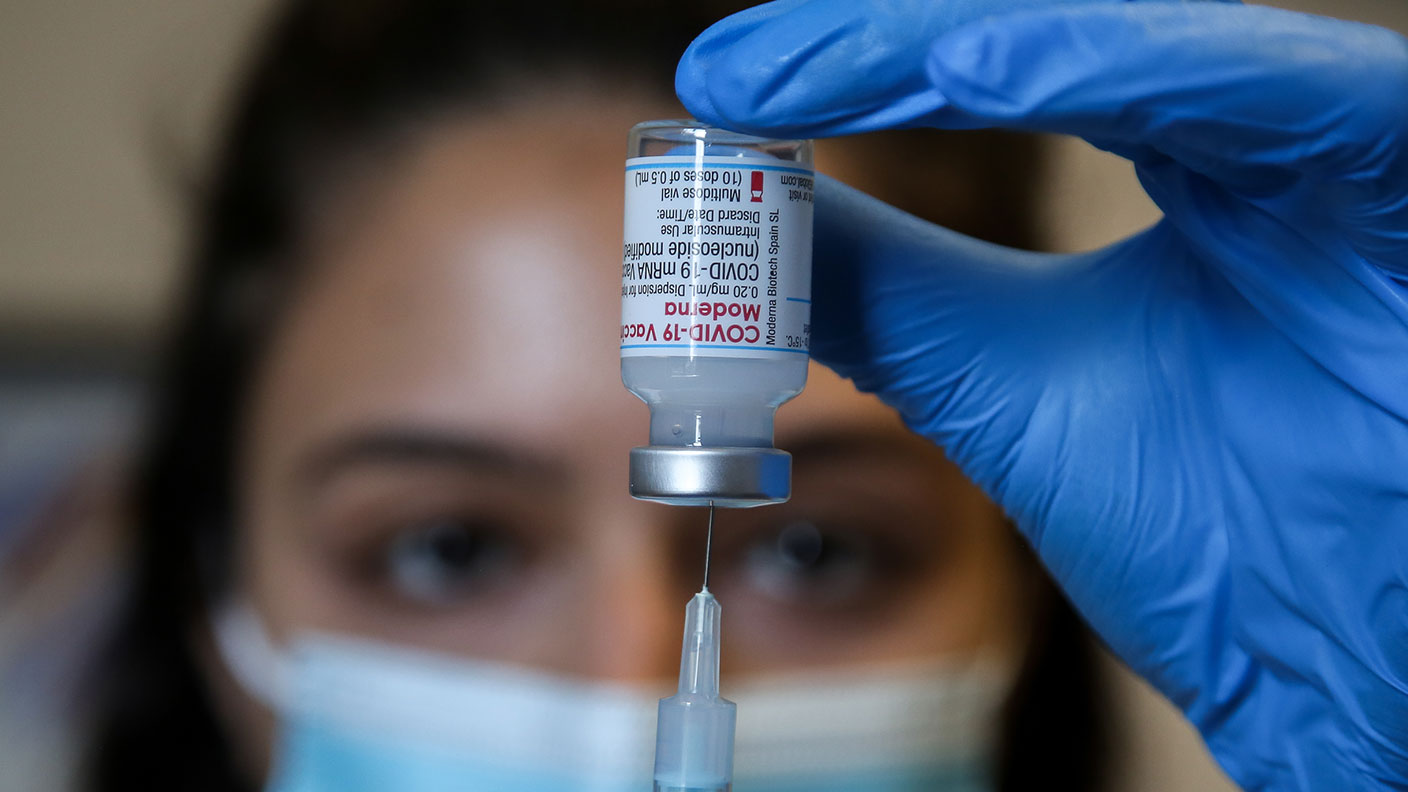

The best vaccine-makers’ stocks to buy now

The rapid development of Covid-19 vaccines has already saved many lives and made huge profits for a few pharmaceutical firms. Investors should keep an eye on other products in their pipelines, says Dr Mike Tubbs.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Over the past two years, many investors will have learned more about vaccines than they ever expected. Most people rarely encounter or think about them outside of our childhood immunisations and the occasional travel requirement. Yet as the pandemic has reminded us, this is a crucial, life-saving area of research – and suddenly a very profitable one for a select handful of successful vaccine developers.

Vaccines protect us from disease by stimulating the production of antibodies that prime the body’s immune system to protect us against specific diseases. They are prepared from the agent responsible for a disease to act as an antigen, but in a way that does not cause the disease. Vaccines can be used against both viral and bacterial diseases. Vaccines cannot guarantee you will never get a disease, but greatly reduce the probability of catching it. If you are infected, they will usually reduce the disease’s severity.

The first vaccine was developed in the UK by Edward Jenner in 1796. He realised milkmaids did not get smallpox because they had had cowpox. He inoculated a boy with cowpox virus and demonstrated the boy’s immunity to smallpox. A smallpox vaccine was developed in 1798 and mass vaccination throughout the 19th and 20th centuries enabled smallpox to be eliminated from the world by 1979.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The Covid-19 pandemic marks a fresh leap forward. Several highly effective vaccines were developed in just under a year, compared with the ten years or more required previously to discover, develop and approve a new vaccine. An extreme example was the Ervebo vaccine for Ebola, which was discovered in 2001 and yet only approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. The incredibly rapid development of Covid-19 vaccines provides a blueprint for future vaccine development.

The race for a vaccine begins

The Covid-19 pandemic started in Wuhan, China, in November 2019. Unfortunately, the Chinese authorities said the virus was viral pneumonia, not a Sars-type virus and, in spite of contrary evidence, denied there was human-to-human transmission until 20 January 2020. Some doctors in Wuhan, including Li Wenliang who later died from the virus, tried to warn about the coronavirus in late December, but were punished for “spreading rumours”.

In early January, around five million people travelled out of Wuhan, many to other countries and this spread the virus worldwide. At the same time, the virus’s genetic sequence was analysed by Chinese researchers, including Zhang Yongzhen, a virologist in Shanghai. On 13 January, he defied instructions and published his data. The Chinese authorities promptly closed his laboratory for “rectification”, but the information was out and laboratories in Western countries started to design both diagnostic tests and vaccines.

Before the pandemic, the major vaccine makers were GlaxoSmithKline (revenues of $9.8bn in 2019), Merck USA ($8.4bn), Sanofi ($6.9bn) and Pfizer ($6.5bn). Vaccines accounted for 21% of GlaxoSmithKline’s turnover and 13%-18% for the others. Some of these companies have ended up playing a major role in the Covid-19 vaccine programmes. Others have not yet had success, while some lesser-known firms – often using innovative technology – have come to the fore.

The most traditional approach to vaccines for both bacterial and viral diseases are those that contain whole bacterial cells or viruses. These are of two types – those using inactivated bacteria/viruses and those using live but attenuated (weakened) bacteria/viruses. However, three other approaches are also now used to create vaccines for viral diseases. These are subunit (also used for bacterial vaccines), viral vector and nucleic acid. Recombinant subunit vaccines use pieces of the pathogen (often protein fragments, such as the spike protein from a coronavirus) to trigger an immune response. The viral vector vaccines work by giving cells genetic instructions to produce antigens, but deliver these instructions using a harmless virus as a carrier. The nucleic acid vaccines (eg, mRNA) work in a similar way to the viral vector ones, but insert genetic RNA or DNA material from the virus into human cells to give instructions to the cells to make the antigen that triggers an immune response.

Who tried what – and what worked

The clear leader of the established vaccine firms has been Pfizer, which teamed up with Germany’s BioNTech to roll out an mRNA vaccine. The UK was the first country to approve this, with vaccinations starting in December 2020, followed by much of the rest of the world. The AstraZeneca and Oxford University vaccine, which uses a viral vector approach, arrived only shortly afterwards. A second mRNA vaccine developed by Moderna has also been widely approved, including by the UK in January 2021. Finally, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen vaccines division launched another viral vector vaccine, which was approved by the UK in May 2021 (and by other countries, including the US, earlier).

In addition to these, Russia produced its Sputnik vaccine using the viral-vector approach. China’s Sinovac/CoronaVac and Sinopharm vaccines use the older inactivated virus technique, as does India’s Covaxin. These have been used widely in emerging economies, but not in the West.

Novavax, a US biotech, has developed a subunit vaccine that performed well in trials, but has been slow to gain regulatory approval due to manufacturing problems. It gained its first regulatory approval in Indonesia in November 2021, was recommended for authorisation in the EU by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) last month and has applied for approval in the UK. The EMA also began reviewing an inactivated virus vaccine with adjuvant (a substance that enhances the immune response to an antigen) from French biotech Valneva in December 2021.

The rapid arrival of so many successful vaccines may seem remarkable, but is partly explained by how many went into urgent development, some of which have been abandoned. To take just other examples involving major developers, Merck had two programmes, but early results were disappointing and it terminated both in January 2021. It is instead helping to make Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine. GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi had disappointing results from their first vaccine candidate so developed an upgraded version, which began phase-III trials in September 2021. This is a recombinant vaccine with GlaxoSmithKline’s adjuvant, as are the firm’s collaborations between South Korea’s SK Bioscience and Canada’s Medicago. Both of these are also in phase-III trials. GlaxoSmithKline is also about to enter trials for an mRNA vaccine developed with CureVac, a German biotech whose first effort at an mRNA was abandoned after weak results. Sanofi has also worked with Translate Bio on an mRNA, but suspended development in September 2021.

Pfizer takes the prize

Thus we see that the smallest of 2019’s four major vaccine manufacturers – Pfizer – has done best so far. Merck is out of the race. GSK has four collaborations with three in phase-III clinical trials. Sanofi has its collaboration with GSK. Meanwhile, three companies not in the top four of 2019 – AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and Moderna – have all had Covid-19 vaccines deployed, while Novavax is finally starting to obtain its first approvals.

Pfizer expects to have made three billion vaccine doses in 2021. Its vaccine sales for the first nine months of 2021 were $28.7bn, or half of its total sales. That compares to its vaccine sales of only $4.6bn for nine months in 2020. Its partner BioNTech – which developed the vaccine (Pfizer handles testing and distribution) – reported its own vaccine sales for the first nine months of 2021 as €500m, but profits from its profit-share agreement with Pfizer were €9.8bn. Moderna, which arranged its own contract manufacturing rather than partnering with a pharma major, expects its vaccine sales for full year 2021 to be $15bn-$18bn, or around half of Pfizer’s expected sales.

AstraZeneca reported Covid-19 vaccine sales of just $2.2bn for the first nine months of 2021, despite setting up 25 manufacturing plants in 15 countries and supplied two billion vaccine doses to 170+ countries by November 2021. This is much lower than Pfizer, since AstraZeneca had initially priced its vaccine at cost to help poorer countries. It said in November that it may now start to make a modest profit from sales. Johnson & Johnson reported Covid-19 vaccine sales of €500m for Q3 and $770m for the first nine months (its vaccine has been deployed less widely and, like AstraZeneca, the company said that it would initially deliver it at low cost). For comparison, GlaxoSmithKline reported vaccine sales of £5bn ($6.7bn) for the first nine months and this includes just £352m of adjuvant sales for Covid-19 vaccines.

Prospects for Covid-19 and beyond

Future sales of coronavirus vaccines will depend on the number of new variants and how severe symptoms are from those variants. Some viruses become less virulent over time and Covid-19 might follow this path. However, it could be that annual Covid-19 vaccinations become routine for sections of the population, as for influenza. The new vaccine platforms, such as viral vector and mRNA, should enable vaccines to be updated in around 100 days to counter new Covid-19 variants. Thus, if annual vaccinations become necessary for vulnerable groups, vaccines can be modified each year to fight the latest variants. This may drive continued sales even when the current pandemic phase is over.

More broadly, vaccines were until recently thought of as stable, good businesses, but not exciting ones. That changed with the advent of Covid-19. Yet uncertainty about the future course of Covid-19 and other possible pandemics creates the main unknown about investing in companies with substantial proportions of revenue from vaccines.

For example, the Sars-1 coronavirus that emerged in China in 2002, causing pneumonia-like symptoms and leading to 8,098 cases and 774 deaths in total, mainly in China and four other countries, was ultimately controlled. Covid-19, by contrast, has already caused 5.4 million deaths and spread to almost every country. If future pandemics were similar to Sars-1, they would provide only modest returns. However, ongoing serious mutations of Covid-19, or a serious pandemic caused by another coronavirus or other pathogen, would generate an urgent need for new vaccines.

The rapid development of Covid-19 vaccines has both demonstrated that vaccine development can be speeded up and introduced new technologies that can form the basis of vaccines for other diseases. So it’s important to look at the full range of potential developments in these companies’ pipelines.

Among the big pharma firms, Pfizer has seven potential new vaccines for diseases ranging from clostridoides difficile in phase III, Lyme disease in phase II and influenza in phase I. GlaxoSmithKline has 15 vaccines in clinical trials, including vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rabies, shingles, meningitis and C. difficile. Merck’s pipeline has two vaccines in phase II and three vaccines approved within the last two years, but gives no phase-I information. Sanofi has ten vaccines in its pipeline, with three of those in phase III for rabies, RSV and meningitis. Johnson & Johnson has four pipeline vaccines in clinical trials for RSV, HIV, Ebola and ExPEC (systemic bacterial infection). AstraZeneca has only RSV and Covid-19 vaccines under development.

Turning to the smaller firms, BioNTech has an mRNA vaccine for influenza in phase-I clinical trials and plans to start clinical trials of an mRNA malaria vaccine and a tuberculosis vaccine in 2022. Moderna has a well-stocked pipeline of 15 different mRNA vaccines for diseases as diverse as RSV, EBV (Epstein-Barr virus), influenza and HIV, with six of them in clinical trials. Novavax has five vaccines in clinical trials, for RSV, influenza and Ebola. Vaccine specialist Valneva has four in trials and two marketed.

Investment options

There are two main options for investing in companies involved in vaccines. The first is to concentrate on large biopharma companies with substantial vaccine interests. Pfizer demonstrated agility in teaming up with BioNTech. GlaxoSmithKline, originally the world leader in vaccines, has at least set up four collaborative programmes that should bear fruit if Covid-19 continues to be a threat for two or more years. However, in the medium term profits for both companies will depend mainly on products other than vaccines. GlaxoSmithKline, for example, has been strengthening its pipeline with emphasis on cancer and HIV as well as infectious diseases. It recently announced the start of human clinical trials in 2022 of a cure for HIV. In addition, it is preparing to spin-off its consumer products division from pharmaceuticals and vaccines into a new listed company. This will reduce the dividend and adds uncertainty about how debt will be allocated and whether proceeds will be reinvested in new pharmaceuticals.

The other major company that showed agility over Covid-19 vaccines is AstraZeneca, but its future depends almost entirely on other products. It has revitalised its whole pipeline over the last few years, added treatments for rare diseases with the acquisition of Alexion in July 2021, and has a particularly strong pipeline of cancer drugs.

Pfizer will benefit the most from Covid-19 vaccines. Analysts forecast earnings per share (EPS) to rise from $2.82 in 2020 to $4.19 for 2021 and $6.04 for 2022, but then fall back to $5.17 for 2023 when the pandemic boost may be reducing. It trades on a forecast price/earnings (p/e) ratio for 2022 of 9.9, rising to 11.5 for 2023. GlaxoSmithKline has a 2022 p/e of 14.1 and AstraZeneca a 2022 p/e of 16.7. Of the three larger companies, AstraZeneca probably has more potential in its pipeline, but for cancer treatments and rare diseases rather than vaccines. It should be compared with other major biopharma companies, not just those with vaccines.

The second choice is to focus on smaller, newer companies using mRNA or viral-vector technology for both Covid-19 and other vaccines and drugs. BioNTech, Moderna and Novavax were all making losses in 2020, but are expected to make good profits in 2021-2023. Forecast EPS for BioNTech is $32.2 for 2022, falling steeply to $18.6 for 2023. Moderna is projected to earn $27.1 for 2022, falling to $13.6 for 2023. Novavax is on $25.7 for 2022, falling to $18.7 for 2023. These decreases from 2022 to 2023 are much larger for the smaller companies than Pfizer because they are much more dependent on vaccines.

In terms of valuation, BioNTech is on a 2022 p/e of 8.1, rising to 14 for 2023. Moderna’s p/e for 2022 is 7.8, rising to 18.5 for 2023. Novavax comes in at 7.1 for 2022, rising to 9.8 for 2023.

Of the three smaller firms, BioNTech is probably the best investment option. In addition to its mRNA-based infectious diseases vaccine pipeline (seasonal influenza, HIV, Malaria and tuberculosis) it has a strong oncology pipeline based on mRNA, CAR-T cell therapy and antibodies with 12 clinical trials in phase I, four in phase II and five at a pre-clinical stage.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Highly qualified (BSc PhD CPhys FInstP MIoD) expert in R&D management, business improvement and investment analysis, Dr Mike Tubbs worked for decades on the 'inside' of corporate giants such as Xerox, Battelle and Lucas. Working in the research and development departments, he learnt what became the key to his investing; knowledge which gave him a unique perspective on the stock markets.

Dr Tubbs went on to create the R&D Scorecard which was presented annually to the Department of Trade & Industry and the European Commission. It was a guide for European businesses on how to improve prospects using correctly applied research and development.

He has been a contributor to MoneyWeek for many years, with a particular focus on R&D-driven growth companies.

-

MoneyWeek news quiz: Can you get smart meter compensation?

MoneyWeek news quiz: Can you get smart meter compensation?Smart meter compensation rules, Premium Bonds winners, and the Bank of England’s latest base rate decision all made the news this week. How closely were you following it?

-

Adventures in Saudi Arabia

Adventures in Saudi ArabiaTravel The kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the Middle East is rich in undiscovered natural beauty. Get there before everybody else does, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Should you sell your Affirm stock?

Should you sell your Affirm stock?Affirm, a buy-now-pay-later lender, is vulnerable to a downturn. Investors are losing their enthusiasm, says Matthew Partridge

-

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategy

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategyYour pension strategy may need tweaking – with many pension experts now arguing that 75 should be the pivotal age in your retirement planning.

-

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global markets

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global marketsBeeks Financial Cloud has carved out a lucrative global niche in financial plumbing with smart strategies, says Jamie Ward

-

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracy

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracyActivist hedge fund Saba Capital isn’t popular, but it has ignited a new age of shareholder engagement, says Rupert Hargreaves

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris

-

Investing in space – finding profits at the final frontier

Investing in space – finding profits at the final frontierGetting into space has never been cheaper thanks to private firms and reusable technology. That has sparked something of a gold rush in related industries, says Matthew Partridge

-

Star fund managers – an investing style that’s out of fashion

Star fund managers – an investing style that’s out of fashionStar fund managers such as Terry Smith and Nick Train are at the mercy of wider market trends, says Cris Sholto Heaton