The best markets in Asia and how to invest in them

China and Indonesia should do well over the next year, while India and Vietnam have exceptional long-term prospects. From tech giants to banks, there are plenty of cheap stocks, says Rupert Foster

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

On 24 October 2020, Alibaba founder Jack Ma gave a now-infamous speech, criticising Chinese regulators for stifling innovation and calling for reforms. Since then, the Chinese internet sector is down by 60% – and by 72% from its subsequent peak high in February 2021. The extent of the collapse is in line with the slump in the Nasdaq in 2000 as the first internet bubble burst. In that case, the Nasdaq didn’t bottom until late 2002, but the subsequent returns have been dramatic. The best stocks are up by eye-watering amounts. Amazon has risen 55,000% since March 2001. Could there be similar opportunities today in the Chinese tech sector?

On the flip side, the best-performing large equity market in the world since the pandemic lows in March 2020 is not the S&P 500 or the Nasdaq, but India’s Sensex. This may come as a surprise: India did not have the resources to follow a Western or Chinese approach to the pandemic, and its economy has historically been adversely affected by a high oil price (the government subsidises the retail gasoline price and thus faces significant fiscal restraint with high oil prices). Does the Sensex’s unexpected strength so far and the extreme dichotomy in performance between Chinese and Indian shares present an opportunity to switch?

China's missteps and changes of direction

Chinese weakness is not solely about tech stocks – the wider CSI 300 index is down 28% since February 2021. This has come about due to a mixture of missteps and structural change in policy from the government.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In the first quarter of 2020, the Chinese government had great success in controlling the spread of Covid-19 with its severe “zero-Covid” strategy. However, that was the peak of its performance. The government then adopted a nationalistic model for its vaccine strategy. Chinese vaccines have proved to be much less effective at combatting Covid. Vaccine hesitancy has also been very prevalent in China. This has left a poorly vaccinated populous who have not attained any natural immunity to Covid because of the initial success of zero-Covid. This stands in stark contrast to Vietnam, which also had a zero-Covid strategy but has fully vaccinated its population, mostly with the AstraZeneca vaccine, and was therefore able to change track months ago.

There have been hints that the Chinese government would get rid of its zero-Covid strategy, but Xi Jinping doubled down on it this week. As yet, there have not been significant imports of foreign vaccines or treatment. Thus another six months of rolling lockdowns would appear likely in China.

The failed pandemic strategy fed a weak macro picture in China in 2021. The previous year was fine, as the Chinese economy benefited from the sharp recovery in consumer spending in the West. However as the West opened up, China stayed closed. This led to falls in consumption. With the government providing limited support to the economy or consumers, growth slowed and is continuing to slow. GDP growth in China in the first half of 2022 is likely to be the slowest in the last 20 years. That said, the government has started loosening both fiscally and monetarily and with Xi ’s eye firmly on his coronation for another five years at the party congress later this year, we should expect the Chinese economy to recover into the second half of the year.

Against this backdrop, the government has chosen to redirect its policies. Xi has said that the government will no longer encourage free-wheeling capitalism but would encourage “common prosperity”. In the West, “levelling up” policies don’t create panic about a return to the high tax regimes of the 1970s, but when you have the Chinese Communist Party in charge, investors are prone to worry over a roll-back of capitalism.

This was compounded by the very public regulatory attacks on the high-flying internet sector. Much of the pain has been born by Jack Ma. Ant Financial, his key asset that was heading for an initial public offering (IPO) before he made his ill-fated speech, has seen radical forced changes to its business model. The broader regulation has been focused on attempting to limit the monopolistic power of platform businesses such as Alibaba and Tencent. That said, it remains difficult to implement these policies and the leading internet companies (bar Ant) have seen little actual effect on their economics from new regulation. What has happened is that the government’s action has had a massive impact on investor sentiment on these companies – and thus their equities have seen a marked decline in valuations.

Chinese stocks are deeply out of favour

This has been exacerbated by earnings weakness. The Chinese internet sector is much more competitive than its Western equivalent – there are many more players in each segment of the market and new companies are arriving all the time. For example, Pinduoduo, the leading group-buying website (it offers significant discounts on a wide range of products if sufficient users commit to buy), has taken significant market share from Alibaba in the last three years, whereas in the West no one is significantly challenging Amazon’s dominance. Thus Alibaba is now going through an aggressive investment cycle to head off competition across a number of its business areas. Coming on top of the weak macro picture in China, this has led Alibaba to have weak earnings in 2021 and into 2022.

Those earnings are set to improve in the second half of 2022. Research from JPMorgan shows that the performance of Chinese tech stocks has tracked short-term earnings expectations. These will turn and the shares will recover. That will be accelerated by the dramatic shift in valuations for these names. Alibaba was once a growth name but now trades on eight times forecast 2022 earnings for its core business. With 40% of its market cap in cash and a free cash-flow yield nearing 10%, this is a deep value stock – but one with earnings set to grow 20% per year for the next three years. The wall of worry around Chinese tech is tough to break down, but investors will in time fight through to take advantage of depressed valuations.

Will Alibaba and its peers return to their halcyon days? Probably not, since the government now has them in its headlights, but they should still trade a lot higher. JPMorgan recently classified the whole Chinese internet sector as “uninvestable”, which looks like one of the great contrary indicators of all time. However, this highlights a problem with investment in Chinese equities in the medium to long term. The US now understands that China is looking to take it on in the great superpower contest at some stage in the next ten to 20 years, and Washington has awoken to the need to hamper China’s charge. That said, policymakers have waited so long that the Chinese economy is now integral to the world and to the US. As a result, significantly harming China will harm America – and so it will have to fight the battle in very specific areas.

Capital markets is one of those areas and this may in time lead to a significant separation in finance and investment. There is already a “China discount” that Western investors apply to all Chinese investments, but that discount appears to be steadily getting larger. Thus the driver of Chinese equities in the medium term will have to be their own domestic investors. Currently most Chinese investors cannot buy Alibaba shares (which are not listed on the mainland), and so there are limited buyers to replace US ones. This will change with rule changes in Hong Kong, but the valuation of Chinese equities may well stay cheap for longer than anticipated while we await the rise of domestic investors.

Indian investors take charge

By comparison, foreign investors have been sellers of Indian equities for the past few months but the index has remained resolute because domestic Indian investors have taken the strain. A burgeoning “cult of equity” is taking hold in India, thanks to the accelerating pace at which Narendra Modi’s government is making necessary structural changes. These will drive a new boom phase of economic development to match that of the early 2000s.

India has always been plagued by the corruption endemic in its politics, which has seeped into the economy and hindered development through the accumulation of bad debts in the banking system and discouraged foreign direct investment. Modi is finally tackling bad debt in the public sector banks through the creation of a “bad bank” (an asset reconstruction company) to take over bad assets and to finally break the link between corrupt politicians and the banking sector. This should allow banks to play an active role in funding much-needed infrastructure and investment in the Indian economy. Corruption remains, but it may become less growth negative. Successful Asian economies have all had corruption, but what was permitted was corruption of a form that is pro-growth. Hopefully India is heading in that direction.

Secondly, and just as importantly, Modi is making India an attractive place for foreign and domestic investment through reform of Indian employment law – with a clear favouritism for domestic businesses. His “Made in India” initiative has been backed by large production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes, under which the government provides significant grants to encourage investment in key areas. One of the most successful has been in mobile phone manufacturing. Dixon Industries has been successful in gaining large PLI backing and has seen its market share in mobile phone manufacturing rise from zero to near 25% in three years. Contract manufacturers such as Foxconn were the cornerstone of Chinese success: Foxconn employs more than one million workers. These businesses are key to employing vast arrays of previously agricultural migrant workers in China – the same could now take place in India. Can Dixon become India’s Foxconn? There now appears no structural reason why not.

The government’s backing of Indian businesses is brave but far-sighted and increasingly looks like allowing long-term growth to accelerate. We must remember that India still remains at a very early stage of development where simple improvements can lead to dramatic accelerations in economic outcomes. Modi is no darling of the Western press because of his Hindu nationalism. However, Lee Kuan Yew did not have a Western approach to democracy, but he had much success in making Singapore a developed nation. India remains a deeply flawed country, but progress is being made and the long-term opportunity remains vast. This will be fuelled in the years ahead by a new burst of credit growth to fund infrastructure and property investment, which may present new challenges.

Chinese equities are likely to bounce hard at some stage in 2022 but long-term investors should continue to favour India over China.

Vietnam and Indonesia – two stars of Southeast Asia

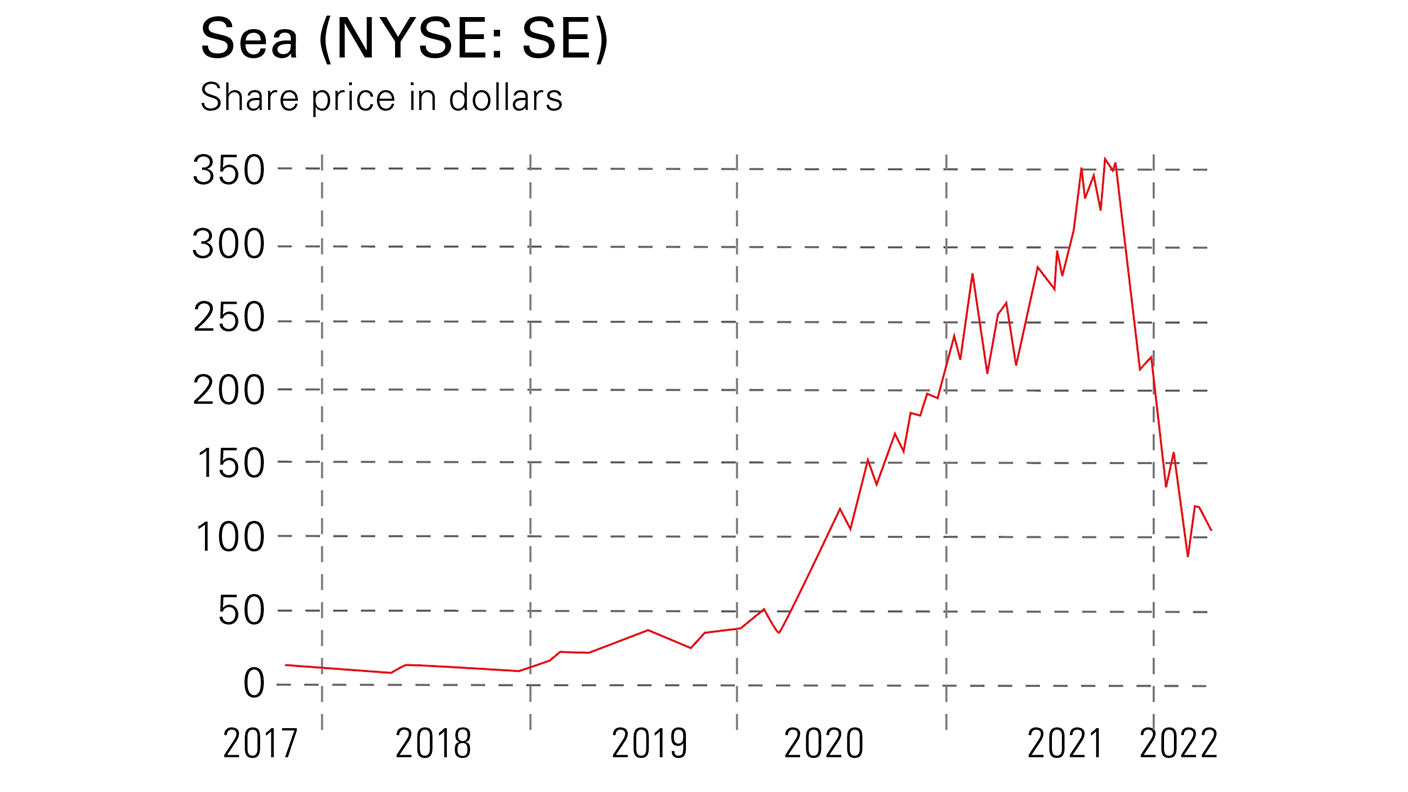

In Southeast Asia, markets are recovering well after a poor 2021. The most attractive market for this year is Indonesia, where high commodity prices will help fuel an economy that is already recovering. The Indonesian stockmarket has seen several tech IPOs in 2021. These have performed poorly because of Western tech valuation trends – although the recent US IPO of ride-hailing, e-commerce and payments firm GoTo was well received. However, their underlying businesses present wonderful investment opportunities for the bold over the next five years. This also applies to US-listed Sea, the biggest Southeast Asian tech name, which has seen over $100bn knocked off its value since September. This company remains well placed to be the e-commerce, gaming and fintech behemoth in Southeast Asia and Latin America. If one share in Asia has similarity to the Amazon opportunity in March 2001, it is this stock.

While Indonesia has the best momentum now, the most interesting Southeast Asian market on a five-year view remains Vietnam. This was the best-performing market in the world in 2021 and is holding up very well so far in 2022. Its top blue chips, such as retailer Mobile World and IT firm FPT, are performing ahead of the US tech giants on a two-to-three year view. The country has performed a miraculous exit from its zero-Covid strategy and opening-up is under way.

That said, the long-term trends are the key drivers of Vietnam. The country may still be run by a nominally communist party, but the government has the pro-growth inclination of China in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This is mixed with realism: Vietnam saw a property bubble burst in 2007 that set back the country’s development by a decade, but has now led to the Vietnamese dong being the most stable currency in Asia (aided by the country’s large oil fields). Vietnam is the key beneficiary of industrial production being moved from China, whether that be shoes, apparel or electronics. It has also opened a new business line as a cheap but high-quality IT outsourcing hub.

Valuations remain very cheap for early-stage high-growth Asian economies. Mobile World, the country’s dominant retailer, trades on 16 times forecast 2022 earnings with a 20%-plus compound annual growth rate over three years. The equivalent in India would trade on double the multiple. The key valuation catalyst will be Vietnam’s reclassification from a frontier market to an emerging market by index compilers such as MSCI. This process takes time, but will happen at some stage in the next couple of years.

Four top investments in Asia’s growth

Sea (NYSE: SE) is the leading e-commerce and fintech player in Southeast Asia and the second player in Latin America. It recently exited India but will return later this year. The stock has collapsed on worries over profitability in the company’s gaming business and lack of profits in e-commerce. However, the Southeast Asian e-commerce business will turn profitable this year and the gaming business will prove much more resilient. Valuations are now close to the depressed levels of Chinese tech stocks, even though it remains the region’s best hope for a $1trn market-cap company.

State Bank of India (NYSE: SBI) is the largest bank in India. It was mired in bad debts and political intervention but Modi has severed those ties, and SBI is now a leading beneficiary of the improved economic fundamentals. The bank has the largest fintech app and the largest credit card business in the country. The valuation remains at base camp on eight times forecast 2023 earnings and a price/book (p/b) ratio of 1.5, despite a return on equity (ROE) of 17% and rising fast. Private sector equivalents trade on a p/b of three with similar ROEs.

Baidu (New York: BIDU, Hong Kong: 9888) is China’s version of Google. It has a search business that trades on six times earnings, with 30% of the market cap in cash. You effectively pay nothing for China’s leading artificial intelligence and smart car businesses, and the third largest cloud computing business in the country. It also has China’s leading robotaxi business and this will break even in the next year. Baidu therefore looks set to drive China’s efforts to lead the world in autonomous vehicles. Deep value at its growthiest!

Vietnam Enterprise Investments (LSE: VEIL) is the largest UK-listed Vietnam trust and has performed better than the main Vietnamese index over the past three years. It has concentrated positions in banks, property and retail. The banking sector in Vietnam remains a key winner, with the added benefit that Vietnam has a credit-growth quota each year and so a credit bust is extremely unlikely.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Rupert is an investment strategist and adviser at J & C Foster, providing Asian, Consumer and Global Equities Strategy advice to a number of family offices and portfolio management organisations. He writes on Asia and Global Macroeconomics for a number of investment publications including MoneyWeek and HL Investment Times.

-

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026Podcast Fidelity's Tom Stevenson reveals his top three funds for 2026 for your ISA or self-invested personal pension

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Should you sell your Affirm stock?

Should you sell your Affirm stock?Affirm, a buy-now-pay-later lender, is vulnerable to a downturn. Investors are losing their enthusiasm, says Matthew Partridge

-

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategy

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategyYour pension strategy may need tweaking – with many pension experts now arguing that 75 should be the pivotal age in your retirement planning.

-

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global markets

Beeks – building the infrastructure behind global marketsBeeks Financial Cloud has carved out a lucrative global niche in financial plumbing with smart strategies, says Jamie Ward

-

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracy

Saba Capital: the hedge fund doing wonders for shareholder democracyActivist hedge fund Saba Capital isn’t popular, but it has ignited a new age of shareholder engagement, says Rupert Hargreaves

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris

-

Investing in space – finding profits at the final frontier

Investing in space – finding profits at the final frontierGetting into space has never been cheaper thanks to private firms and reusable technology. That has sparked something of a gold rush in related industries, says Matthew Partridge

-

Star fund managers – an investing style that’s out of fashion

Star fund managers – an investing style that’s out of fashionStar fund managers such as Terry Smith and Nick Train are at the mercy of wider market trends, says Cris Sholto Heaton