Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

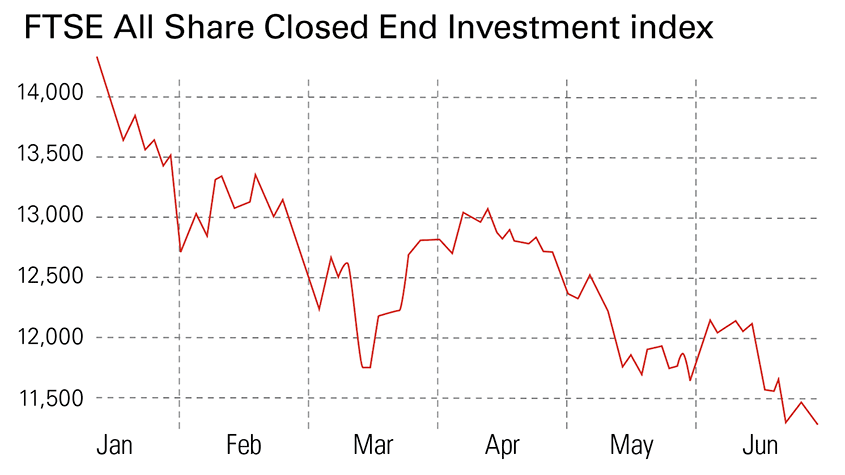

It has been a terrible six months for investment trusts. The FTSE All Share Closed End Investments index slumped by 18.9% compared with a fall of 4.6% for the FTSE All-Share index. Compared with global equities, the performance is better as the MSCI All Countries World index lost 11% in sterling. With the average discount to net asset value (NAV) in the sector widening to 9.8% from 1.5%, the underlying assets performed broadly in line with global equities.

After a stunning 2020, 2021 hadn’t been a great year, with the Closed End Investments index returning 12.8%, compared with 19.6% for the MSCI index. That was despite a fall in average discounts, but this year it seems that investors are losing faith in the investment-trust structure.

Value has eclipsed growth

Equity trusts had become increasingly focused on “growth” investing – partly the result of the outperformance of growth over value over many years, and partly due to the heavy focus of equity issuance on “growth” areas.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This explains why the UK market, with its high weighting in resources and value stocks, has outperformed this year. But although funds investing in the UK are still over-represented in the investment-trust sector, it has become increasingly global in recent decades.

While the MSCI ACWI Growth index lost 19.6% in the first half of 2022, the corresponding value index lost just 2.2%. Technology and technology-related companies, including biotech, had soared in previous years, but fell sharply, due to disappointing earnings, a revaluation of prospects, and contagion from the casualties.

This hit Baillie Gifford, the star fund management company of earlier years, hard. Its trusts accounted for six of the ten worst performers, including Schiehallion, its private-equity trust, down 52.7% and US Growth down 52%. Equity trusts are also heavily overweight in mid- and small-cap companies around the world and while these have a consistent record of outperformance in the long term, 2022 has been the exception to the rule.

Even in the UK, where the FTSE 100 lost just 3% in capital terms, the FTSE 250 index dropped 20%. Moreover, while the FTSE 100, along with other large-cap indices, appeared to have bottomed in mid-June, small and mid-cap indices continued to fall.

The healthcare sector has the image of being a “growth” sector, but trades at a discount to the market in the US, so it qualifies as “value”. It also performed poorly, although the focus of the investment trusts specialising in this area on biotechnology rather than the integrated major companies exacerbated their poor showing. However, there were signs of a sustained recovery by the end of the half.

Japan, once perennially expensive but now perennially cheap, also performed poorly, held back by the weakness of the yen. Emerging markets disappointed too, despite appearing cheap, but performance in recent years was an illusion. It had been propelled by the technology sector, particularly the Chinese giants, such as Alibaba and Tencent, but a clampdown by the Chinese authorities sent their shares tumbling. A tentative recovery now appears to be under way.

Good news on performance, valuations and disposals failed to sustain the private-equity sector, where discounts to NAV widened precipitously as NAVs rose and share prices fell. Investors believe either that the numbers are wrong, or that the fortunes of the sector are about to plunge, so they are following the herd rather than the experts. Even if the herd is right, reality is rarely as bad as feared.

Sentiment has also been hit by the unfolding disaster of Chrysalis Investments, regularly disparaged in MoneyWeek. Chrysalis lost 56.5%, making it the worst performer of all trusts. Remarkably, though, Literacy Capital, floated with little fanfare in mid-2021, returned 36%, making it the second-best performer in the investment-trust sector after Riverstone Energy, up 47%. Riverstone Energy, however, had been a disastrous performer in 2019 and 2020 so its share price remains at only half its peak.

Commodities come back to earth

The resources sector was the bright spot in the market, but its fortunes turned abruptly when commodity prices showed signs of peaking. BlackRock World Mining Trust’s share price rose 34% to a mid-April high, but then lost nearly all of its gains. At least the trust pays a generous dividend.

Also performing well was the “flexible investment” sector, including funds such as Ruffer, Capital Gearing, Personal Assets and RIT. They seek to protect investors in bear markets at the expense of underperformance in bull markets by investing in non-equity asset classes such as inflation-linked bonds, precious metals and infrastructure funds.

On average, these funds still lag global equities over three and five years, but RIT (despite poor performance in the first half), and Caledonia Investments are honourable exceptions, while Ruffer has been on a roll in the last three years. The other bright spot was the alternative-income sector, comprising property trusts (Reits), infrastructure, alternative energy and debt funds. This has been the growth area of the market and good performance almost across the board in the first half seemed to justify it.

The combination of generous, steadily rising dividend yields with moderate capital growth from businesses with low economic sensitivity and good inflation protection has proved attractive.

According to the Association of Investment Companies, in the last ten years equity trusts have fallen from 76% of the total (5% private equity) to 56% (12% private equity), with all the growth coming from alternative income and the flexible investment sectors. This trend continued in the first half, with nearly all the £2.4bn of new issuance, compared with £9.5bn for the whole of 2021, accounted for by these sectors.

There were no new issues in the first half, although this is more of a problem for the corporate brokers than for investors. There are gaps in the market – notably in conventional energy – but specialist managers have proved reluctant to float a trust, knowing that the best time to launch one was when energy prices were low and investors weren’t interested.

Closed-end funds remain popular

The AIC shows investment trust assets down from £280bn to £265bn, still the second highest on record, so their growing popularity over open-ended funds looks likely to endure. However, the rise in trust discounts, which has exacerbated poor performance, is a warning sign that patience is wearing thin.

The second half should bring better market conditions, but there could be more shocks and surprises over the summer. Sentiment is very negative, which is a positive indicator for markets as it implies that there is little room for deterioration.

But with economic growth slowing, developed markets facing – or already in – at least a mild recession and analysts reducing earnings forecasts, further patience may be required.

Inflation is probably peaking in the US and close to a peak in the UK and Europe, but how far and fast it falls back depends on energy prices. The oil price is back below $100 a barrel and future prices are at large discounts to current ones, but this trend could reverse.

Interest rates have further to rise, with the US Federal Reserve expected to raise US rates by 0.75% in July and as much again in September, but that should mark the peak. Government bond yields already appear to have peaked with the yield on the ten-year US Treasury back below 3%, having reached 3.4%, though ten-year gilt yields under 2.5% still look anomalously low. The good news is undoubtedly tentative, but markets never wait for certainty before they rally.

As historian Niall Ferguson says, “there’s a lot of doom and gloom in the air and the profession of being Dr Doom is a very popular one in the US – all you have to do is predict a financial disaster every year. There is very little mileage for the view that everything will be okay”.

We may not be facing “the Roaring Twenties”, but Ferguson points out that the 1920s “were not great anywhere outside the US” and represented an economic bubble that imploded in 1929.

“If the 2020s do end up resembling the 1970s,” he adds, “at least the 1970s were fun, when ‘we’re doomed’ was a comic tagline, not an obsession.”

If we’re not doomed, equity markets will rebound and investment trusts, helped by moderate borrowings, will outperform. Buyers will return in force and discounts could narrow as rapidly as they have widened, resulting in outsized returns. Whether that happens in the second half of 2022 or the first half of 2023 hardly matters. Unless you believe that markets are heading a lot lower, waiting risks missing out.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026

MoneyWeek Talks: The funds to choose in 2026Podcast Fidelity's Tom Stevenson reveals his top three funds for 2026 for your ISA or self-invested personal pension

-

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy now

Three companies with deep economic moats to buy nowOpinion An economic moat can underpin a company's future returns. Here, Imran Sattar, portfolio manager at Edinburgh Investment Trust, selects three stocks to buy now

-

Ashoka: A new, but reliable, trust you can count on

Ashoka: A new, but reliable, trust you can count onOur investment columnist, Max King, says tough times breed investment trusts like Ashoka, that you can trust.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

4 funds for global growth

4 funds for global growthFactor funds are a cheap way to build a portfolio with less bias towards technology or America, says David C Stevenson.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax