What's driving the cost of living crisis?

Soaring bills, inflation and tax rises are about to squeeze household incomes. And it doesn’t seem that there is much the government can do about it.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happening?

A triple whammy of soaring energy costs, galloping inflation and tax rises is about to whack UK households, with some economists predicting a cut in real incomes worse than that seen during the financial crisis of 2008. Inflation as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) was 5.1% in the 12 months to November 2021 (up from 4.2% in October, and more than twice the Bank of England’s target rate). The old retail price index measure of inflation is already at 7.1% – one reason why ministers insist it is “no longer an official measure”.

On tax, national insurance rises in April, plus a freeze on thresholds (another form of real tax rises), means that Britain is heading for its highest overall tax burden since the 1950s. And energy bills are set to soar, also in April, with a YouGov poll showing that one in three Britons think they won’t be able to pay their energy bills this year.

What’s up with energy?

In early February the energy watchdog Ofgem will announce the new maximum price for energy bills. Because the market price of gas is now vastly higher than when the cap was last set, that maximum could easily go from £1,277 for an average household to above £2,000, twice what it was last winter.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That extra £723 is equivalent to about 3% of disposable income (after housing costs) for a household on (median) average income – in other words a “hit to living standards of a sizeable recession”, calculates Chris Giles in the Financial Times.

Together with tax rises, the Resolution Foundation calculates that the average household stands to lose an extra £1,200 a year. And that’s before you take account of the impact of energy prices on inflation. Goldman Sachs reckons the April price hikes will take the CPI inflation rate from that 5.1% to 6.8%, the highest rate for 30 years.

What can the government do?

It could remove VAT on energy. Before the EU referendum of 2016 Boris Johnson argued that an upside of Brexit would be the freedom to “scrap this unfair and damaging tax”. Now, he says, removing VAT would be a “blunt instrument” that wouldn’t direct help towards those in most dire financial need. He is right, says David Gauke in the New Statesman – and the unlikely alliance of Labour and Tory rightwingers calling for such a move are wrong.

The typical household saving would be just £90 a year: far better to target help at the worst affected (as the government has hinted it will). Another option would be for the government to extend a credit line to energy providers, allowing a smoothing out of price rises for consumers. Given the unpredictability of gas prices, that’s a risk the Treasury is unlikely to embrace, says The Times – especially given the precedent it would set for other industries subject to volatile commodity prices.

Similarly, the removal of green levies (of around £150 a year on average) “would be little more than tinkering and would be deceptive if general taxation then merely took up the burden”.

So there are no good options?

None that will save the government political pain. The roots of the problem are global, says Jeremy Warner in The Daily Telegraph, yet it has “been made very much worse in the UK by years of short-sighted, populist energy policy” that encouraged short-termism and unrealistic price-setting. The long-term solutions to the UK’s rising taxes and energy bills “lie in radical reform of healthcare spending and energy markets”.

Yet even if we had a strong government bold enough to take the plunge, it wouldn’t solve the immediate problem. “Unless saved by rising wages, ministers are about to stumble out of Covid-19 straight into the path of an oncoming lorry marked Lower Living Standards” – and there’s nothing they can do.

What’s the broader context?

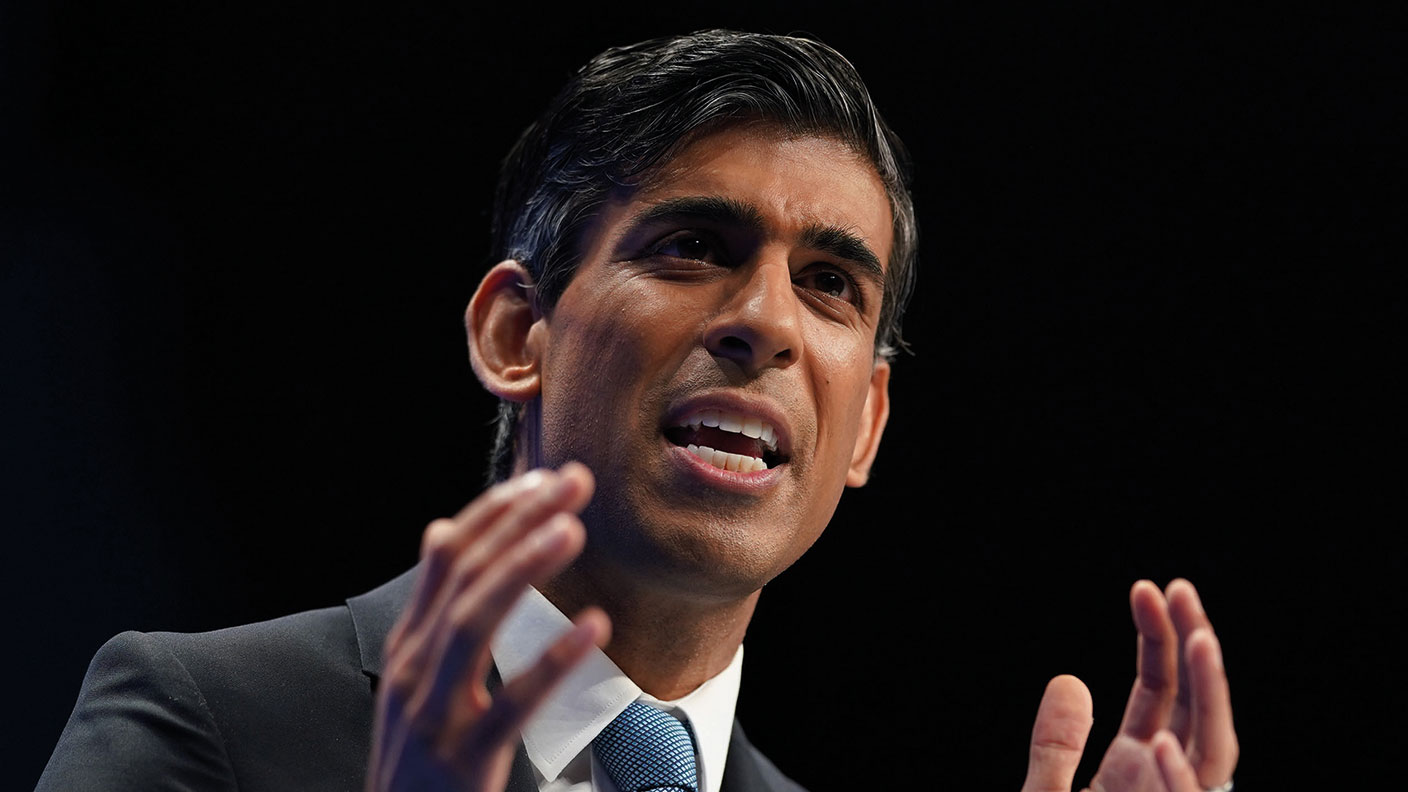

The broader context is a government struggling to emerge from the pandemic with a convincing agenda, a governing party increasingly divided over fiscal policy, and a prime minister weakened by questions over his integrity.

The Johnson administration appears to have no plan to deal with the crisis, says The Daily Telegraph – and “has yet to detail a credible set of policies, including genuine deregulation, pro-growth tax reform and higher quality skills, to boost productivity and wages across the board”.

The government claims it wants to deliver a “high wage, high productivity economy”, says the Financial Times – but for now it “must focus on heading off a high-cost, high-poverty one instead”.

But isn’t the UK getting richer?

The UK has got richer over the past half century, but the share of wealth taken by labour has fallen, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Increases in productivity will pass through to higher labour income – and hence drive real higher living standards – only if the labour share of income is constant or growing. If not, those productivity gains are captured by businesses as lower operating costs (lower unit labour costs), increased business profits and lower consumer prices.

ONS data shows that the labour share of income falling. In the period 1955-1970, the average share was about 70%. But it fell steadily between the mid-1970s and the mid-1990s, and since the turn of the century, it’s been broadly flat at around 60%. A similar trend can be seen in the US, and many other rich economies. That is a context in which lower paid workers are unlikely to have much ability to weather a dramatic shift in their living standards.

The public has been “remarkably forgiving” of the government’s missteps during the pandemic, says The Spectator. But the soured mood over lockdown-flouting parties will turn far nastier when voters find their real incomes shrinking and bills soaring. “A government which owes its existence to a newfound ability to reach relatively low-income voters is fast approaching a crisis which could turn out to be terminal.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?

-

What turns a stock market crash into a financial crisis?

What turns a stock market crash into a financial crisis?Opinion Professor Linda Yueh's popular book on major stock market crashes misses key lessons, says Max King

-

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher eraOpinion With the ISA under attack, the Labour government has now started to destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era, returning the economy to the dysfunctional 1970s

-

Why does Trump want Greenland?

Why does Trump want Greenland?The US wants to annex Greenland as it increasingly sees the world in terms of 19th-century Great Power politics and wants to secure crucial national interests